A tort is a civil wrong that causes a claimant to suffer loss or harm, resulting in legal liability for the person who commits the tortious act. Tort law can be contrasted with criminal law, which deals with criminal wrongs that are punishable by the state. While criminal law aims to punish individuals who commit crimes, tort law aims to compensate individuals who suffer harm as a result of the actions of others. Some wrongful acts, such as assault and battery, can result in both a civil lawsuit and a criminal prosecution in countries where the civil and criminal legal systems are separate. Tort law may also be contrasted with contract law, which provides civil remedies after breach of a duty that arises from a contract. Obligations in both tort and criminal law are more fundamental and are imposed regardless of whether the parties have a contract.

In the field of jurisprudence, equity is the particular body of law, developed in the English Court of Chancery, with the general purpose of providing legal remedies for cases wherein the common law is inflexible and cannot fairly resolve the disputed legal matter. Conceptually, equity was part of the historical origins of the system of common law of England, yet is a field of law separate from common law, because equity has its own unique rules and principles, and was administered by courts of equity.

A writ of prohibition is a writ directing a subordinate to stop doing something the law prohibits. This writ is often issued by a superior court to the lower court directing it not to proceed with a case which does not fall under its jurisdiction.

A quasi-contract is a fictional contract recognised by a court. The notion of a quasi-contract can be traced to Roman law and is still a concept used in some modern legal systems. Quasi contract laws have been deduced from the Latin statement "Nemo debet locupletari ex aliena iactura", which proclaims that no one should grow rich out of another person's loss. It was one of the central doctrines of Roman law.

Restitution and unjust enrichment is the field of law relating to gains-based recovery. In contrast with damages, restitution is a claim or remedy requiring a defendant to give up benefits wrongfully obtained. Liability for restitution is primarily governed by the "principle of unjust enrichment": A person who has been unjustly enriched at the expense of another is required to make restitution.

Replevin or claim and delivery is a legal remedy which enables a person to recover personal property taken wrongfully or unlawfully, and to obtain compensation for resulting losses.

In tort law, detinue is an action to recover for the wrongful taking of personal property. It is initiated by an individual who claims to have a greater right to their immediate possession than the current possessor. For an action in detinue to succeed, a claimant must first prove that he had better right to possession of the chattel than the defendant, and second, that the defendant refused to return the chattel once demanded by the claimant.

Assumpsit, or more fully, action in assumpsit, was a form of action at common law used to enforce what are now called obligations arising in tort and contract; and in some common law jurisdictions, unjust enrichment. The origins of the action can be traced to the 14th century, when litigants seeking justice in the royal courts turned from the writs of covenant and debt to the trespass on the case.

Trover is a form of lawsuit in common law jurisdictions for recovery of damages for wrongful taking of personal property. Trover belongs to a series of remedies for such wrongful taking, its distinctive feature being recovery only for the value of whatever was taken, not for the recovery of the property itself.

The writs of trespass and trespass on the case are the two catchall torts from English common law, the former involving trespass against the person, the latter involving trespass against anything else which may be actionable. The writ is also known in modern times as action on the case and can be sought for any action that may be considered as a tort but is yet to be an established category.

In the Roman litigation system, while the Legis Actiones procedure was in force during the early Republic, both parties had to lay down a legal wager at the preliminary hearing, probably to discourage frivolous litigation. In some cases, if the party lost, the wager went to the other party, to compensate him for his inconvenience, rather than to the court to cover costs.

Fibrosa Spolka Akcyjna v Fairbairn Lawson Combe Barbour Ltd[1942] UKHL 4 is a leading House of Lords decision on the doctrine of frustration in English contract law.

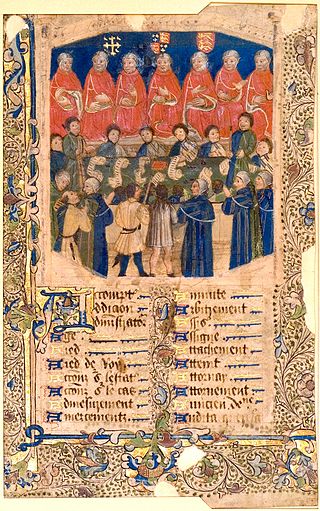

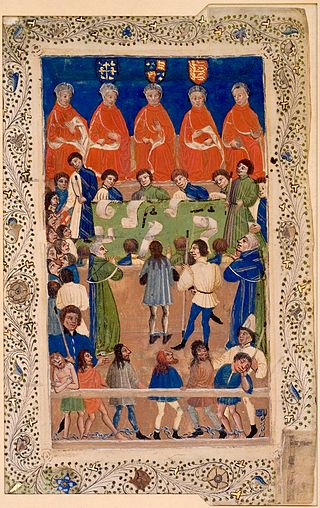

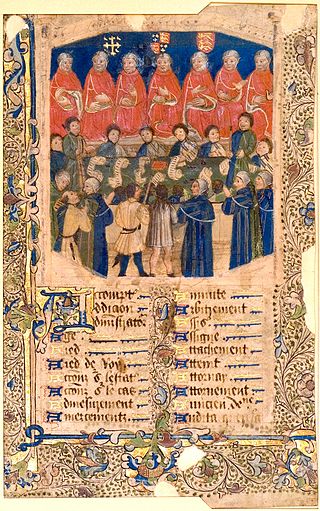

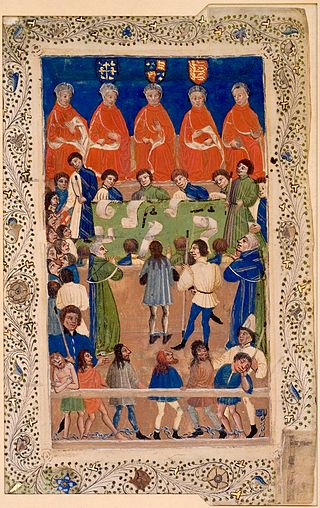

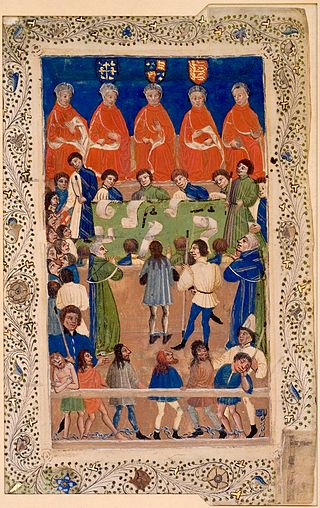

The Court of Common Pleas, or Common Bench, was a common law court in the English legal system that covered "common pleas"; actions between subject and subject, which did not concern the king. Created in the late 12th to early 13th century after splitting from the Exchequer of Pleas, the Common Pleas served as one of the central English courts for around 600 years. Authorised by Magna Carta to sit in a fixed location, the Common Pleas sat in Westminster Hall for its entire existence, joined by the Exchequer of Pleas and Court of King's Bench.

The Bill of Middlesex was a legal fiction used by the Court of King's Bench to gain jurisdiction over cases traditionally in the remit of the Court of Common Pleas. Hinging on the King's Bench's remaining criminal jurisdiction over the county of Middlesex, the Bill allowed it to take cases traditionally in the remit of other common law courts by claiming that the defendant had committed trespass in Middlesex. Once the defendant was in custody, the trespass complaint would be quietly dropped and other complaints would be substituted.

Conversion is an intentional tort consisting of "taking with the intent of exercising over the chattel an ownership inconsistent with the real owner's right of possession". In England and Wales, it is a tort of strict liability. Its equivalents in criminal law include larceny or theft and criminal conversion. In those jurisdictions that recognise it, criminal conversion is a lesser crime than theft/larceny.

The English law of unjust enrichment is part of the English law of obligations, along with the law of contract, tort, and trusts. The law of unjust enrichment deals with circumstances in which one person is required to make restitution of a benefit acquired at the expense of another in circumstances which are unjust.

The Court of King's Bench, formally known as The Court of the King Before the King Himself, was a court of common law in the English legal system. Created in the late 12th to early 13th century from the curia regis, the King's Bench initially followed the monarch on his travels. The King's Bench finally joined the Court of Common Pleas and Exchequer of Pleas in Westminster Hall in 1318, making its last travels in 1421. The King's Bench was merged into the High Court of Justice by the Supreme Court of Judicature Act 1873, after which point the King's Bench was a division within the High Court. The King's Bench was staffed by one Chief Justice and usually three Puisne Justices.

Baltic Shipping Company v Dillon, the Mikhail Lermontov case, is a leading Australian contract law case, on the incorporation of exclusion clauses and damages for breach of contract or restitution for unjust enrichment.

Slade's Case was a case in English contract law that ran from 1596 to 1602. Under the medieval common law, claims seeking the repayment of a debt or other matters could only be pursued through a writ of debt in the Court of Common Pleas, a problematic and archaic process. By 1558 the lawyers had succeeded in creating another method, enforced by the Court of King's Bench, through the action of assumpsit, which was technically for deceit. The legal fiction used was that by failing to pay after promising to do so, a defendant had committed deceit, and was liable to the plaintiff. The conservative Common Pleas, through the appellate court the Court of Exchequer Chamber, began to overrule decisions made by the King's Bench on assumpsit, causing friction between the courts.

A penal bond is a written instrument executed between an obligor and an obligee designed to secure the performance of a legal obligation through the in terrorem effect of the threat of a penalty for nonperformance.