Related Research Articles

Abū Ḥāmid Muḥammad ibn Muḥammad al-Ṭūsiyy al-Ghazali, known commonly as Al-Ghazali, known in Medieval Europe by the Latinized Algazelus or Algazel, was a Persian Sunni Muslim polymath. He is known as one of the most prominent and influential jurisconsults, legal theoreticians, muftis, philosophers, theologians, logicians and mystics in Islamic history.

Ash'arism is a school of theology in Sunni Islam named after Abu al-Hasan al-Ash'ari, a Shāfiʿī jurist, reformer (mujaddid), and scholastic theologian, in the 9th–10th century. It established an orthodox guideline, based on scriptural authority, rationality, and theological rationalism. It is one of the three main schools alongside Maturidism and Atharism.

Ilm al-kalam or ilm al-lahut, often shortened to kalam, is the scholastic, speculative, or rational study of Islamic theology (aqida). It can also be defined as the science that studies the fundamental doctrines of Islamic faith, proving their validity, or refuting doubts regarding them. Kalām was born out of the need to establish and defend the tenets of Islam against the philosophical doubters. A scholar of kalam is referred to as a mutakallim, a role distinguished from those of Islamic philosophers and jurists.

Ibn Taymiyya was a Sunni Muslim scholar, jurist, traditionist, ascetic, and proto-Salafi and iconoclastic theologian. He is known for his diplomatic involvement with the Ilkhanid ruler Ghazan Khan at the Battle of Marj al-Saffar, which ended the Mongol invasions of the Levant. A legal jurist of the Hanbali school, Ibn Taymiyya's condemnation of numerous folk practices associated with saint veneration and visitation of tombs made him a contentious figure with many rulers and scholars of the time, which caused him to be imprisoned several times as a result.

Liberalism and progressivism within Islam involve professed Muslims who have created a considerable body of progressive thought about Islamic understanding and practice. Their work is sometimes characterized as "progressive Islam". Some scholars, such as Omid Safi, differentiate between "progressive Muslims" versus "liberal advocates of Islam". Liberal Islam originally emerged out of the Islamic revivalist movement of the 18th–19th centuries. Liberal and progressive ideas within Islam are considered controversial by some traditional Muslims, who criticize liberal Muslims on the grounds of being too Western and/or rationalistic.

Occasionalism is a philosophical doctrine about causation which says that created substances cannot be efficient causes of events. Instead, all events are taken to be caused directly by God. The doctrine states that the illusion of efficient causation between mundane events arises out of God's causing of one event after another. However, there is no necessary connection between the two: it is not that the first event causes God to cause the second event: rather, God first causes one and then causes the other.

The Salafi movement or Salafism is a revival movement within Sunni Islam, which was formed as a socio-religious movement during the late 19th century and has remained influential in the Islamic world for over a century. The name "Salafiyya" is a self-designation, to call for a return to the traditions of the "pious predecessors", the first three generations of Muslims, who are believed to exemplify the pure form of Islam. In practice, Salafis claim that they rely on the Qur'an, the Sunnah and the Ijma (consensus) of the salaf, giving these writings precedence over what they claim as "later religious interpretations". The Salafi movement aimed to achieve a renewal of Muslim life and had a major influence on many Muslim thinkers and movements across the Islamic world.

Pan-Islamism is a political movement which advocates the unity of Muslims under one Islamic country or state – often a caliphate – or an international organization with Islamic principles. Historically, after Ottomanism, which aimed at the unity of all Ottoman citizens, Pan-Islamism was promoted in the Ottoman Empire during the last quarter of the 19th century by Sultan Abdul Hamid II for the purpose of preventing secession movements of the Muslim peoples in the empire.

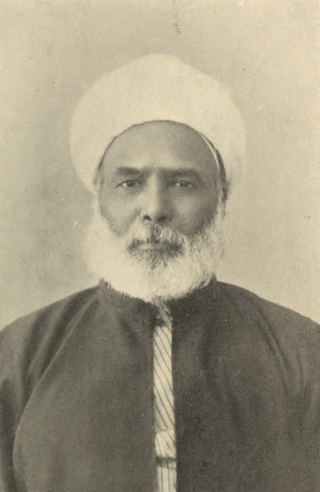

Muḥammad ʿAbduh was an Egyptian Islamic scholar, judge, and Grand Mufti of Egypt. He was a central figure of the Arab Nahḍa and Islamic Modernism in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

The Incoherence of the Philosophers is a landmark 11th-century work by the Muslim polymath al-Ghazali and a student of the Asharite school of Islamic theology criticizing the Avicennian school of early Islamic philosophy. Muslim philosophers such as Ibn Sina (Avicenna) and al-Farabi (Alpharabius) are denounced in this book, as they follow Greek philosophy even when, in the author's perception, it contradicts Islam. The text was dramatically successful, and marked a milestone in the ascendance of the Asharite school within Islamic philosophy and theological discourse.

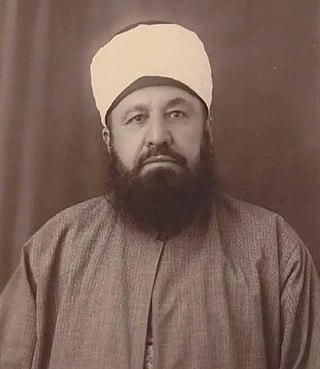

Muhammad Rashid Rida was an Islamic scholar, reformer, theologian and revivalist. An early Salafist, Rida called for the revival of hadith studies and, as a theoretician of an Islamic state, condemned the rising currents of secularism and nationalism across the Islamic world following the abolition of the Ottoman sultanate. He championed a global pan-Islamist program aimed at re-establishing an Islamic caliphate.

Abu Bakr ibn al-Arabi was a Muslim judge and scholar of Maliki law from al-Andalus. Like Al-Mu'tamid ibn Abbad, Ibn al-Arabi was forced to migrate to Morocco during the reign of the Almoravids. It is reported that he was a student of Al-Ghazali. He was a master of Maliki Jurisprudence. His father was a student of Ibn Hazm. He also contributed to the spread of Ash'ari theology in Spain. A detailed biography about him was written by his contemporary Qadi Ayyad, the Malikite scholar and judge from Ceuta.

Abd al-Hamīd ibn Mustafa ibn Makki ibn Badis, better known as Ibn Badis was an Algerian Salafi educator, exegete, Islamic reformer, scholar and figurehead of cultural nationalism. In 1931, Ben Badis founded the Association of Algerian Muslim Ulema, which was a national grouping of many Islamic scholars in Algeria from many different and sometimes opposing perspectives and viewpoints. The Association would have later a great influence on Algerian Muslim politics up to the Algerian War of Independence. In the same period, it set up many institutions where thousands of Algerian children of Muslim parents were educated. The Association also published a monthly journal, the Al-Chihab and Souheil Ben Badis contributed regularly to it between 1925 and his death in 1940. The journal informed its readers about the Association's ideas and thoughts on religious reform and spoke on other religious and political issues.

Islamic modernism is a movement that has been described as "the first Muslim ideological response to the Western cultural challenge", attempting to reconcile the Islamic faith with values perceived as modern such as democracy, civil rights, rationality, equality, and progress. It featured a "critical reexamination of the classical conceptions and methods of jurisprudence", and a new approach to Islamic theology and Quranic exegesis (Tafsir). A contemporary definition describes it as an "effort to re-read Islam's fundamental sources—the Qur'an and the Sunna, —by placing them in their historical context, and then reinterpreting them, non-literally, in the light of the modern context."

Atharism is a school of theology in Sunni Islam which developed from circles of the Ahl al-Hadith, a group that rejected rationalistic theology in favor of strict textualism in interpretation the Quran and the hadith.

Tafwid is an Arabic term meaning "relegation" or "delegation", with uses in theology and law.

Jamal al-Din bin Muhammad Saeed bin Qasim al-Hallaq al-Qasimi was a Muslim scholar in Damascus during the Ottoman Empire. He was a leader of the Salafi movement and a prolific author who wrote many books about Islamic law.

Tahir al-Jaza'iri was a 19th century Syrian Muslim scholar and educational reformer and a great scholar of Tafsīr, Ḥadīth, Fiqh, Uṣūl, history and the Arabic language.

Arab Salafi movement of early 20th century led by Syrian Salafi theologian Muhammad Rashid Rida championed various beliefs such as Pan-Islamism, anti-colonialism, revival of Athari theology based on the works of medieval theologian Ibn Taymiyya as well as rejection of partisanship to legal schools (mad'habs). After his death, Rida's ideas would later on be expanded by his disciples in varied ways. One such disciple, Abu Ya'la al Zawawi called for the creation of a committee of ulama to reconcile various Sunni legal mad'habs. The ultimate goal was the promotion of a single school of thought for all Muslims, “a pure ancestral madhhab [madhhaban salafiyyan mahdan], be it in creed or in worship and other religious practices.” Others such as Muhammad Munir al-Dimishqi would come to the defense of the mad'habs. He also condemned those who invited Muslims to act according to Qur'an and Sunnah alone without taqleed (imitation) or ittiba (following) of the 4 schools. Conveying his pro-madhab message, Munir asserted that taqleed (blind-following) is not dispensable for modern Muslims. Scholars like Mas'ud 'Alam al-Nadwi defined the Salafi movement in vague terms as "the movement of decisive revolution against stagnancy". Thus different notions of Salafi legal doctrines emerged amongst Rida's followers and competed for dominance. Some, like that of Munir remained marginal.

References

- ↑ "Frank Griffel". Yale University – Religious Studies. Retrieved 2021-10-21.

- ↑ "New appointment establishes Oxford as a "major centre" for the study of Islamic philosophy and theology". Oxford University - Faculty of Theology and Religion. Retrieved 2024-11-06.

- ↑ Reviews of Al-Ghazali's Philosophical Theology:

- Whittingham, Martin (2010). "Al-Ghazali's Philosophical Theology". American Journal of Islam and Society. 27 (4). International Institute of Islamic Thought: 111–114. doi: 10.35632/ajis.v27i4.1295 . ISSN 2690-3741.

- Journal of the American Oriental Society, Vol. 130, No. 1 (January–March 2010), pp. 118-121

- Review of Middle East Studies, Vol. 44, No. 1 (Summer 2010), pp. 82-84

- Zeitschrift der Deutschen Morgenländischen Gesellschaft, Vol. 163, No. 1 (2013), pp. 244-246

- Philosophy East and West, Vol. 61, No. 3 (JULY 2011), pp. 564-567

- Journal of Near Eastern Studies, Vol. 71, No. 2 (October 2012), pp. 398-400

- Journal of Qur'anic Studies, Vol. 13, No. 2 (2011), pp. 115-128

- Otto, Sean (2016-01-27). "Al-Ghazali's Philosophical Theology". The Heythrop Journal. 57 (2). Wiley: 415–416. doi:10.1111/heyj.46_12316. ISSN 0018-1196.

- Janssens, Jules (2011). "Al-Ghazālī's Philosophical Theology". The Muslim World. 101 (1). Wiley: 115–119. doi:10.1111/j.1478-1913.2010.01346.x. ISSN 0027-4909.

- Kılıç, Muhammet Fatih. SCIRES-IT , Jul2011, Vol. 1 Issue 2, p. 133-137

- Ragep, F. Jamil. In: Isis. Dec 2010, Vol. 101 Issue 4, p867

- ↑ Griffel, Al-Ghazālī’s Philosophical Theology, p. 11.

- ↑ Griffel, Al-Ghazālī’s Philosophical Theology, p. 6.

- ↑ Griffel, The Formation of Post-Classical Philosophy in Islam, pp. 552–560, 571.

- ↑ Henri Lauzière, “The Construction of Salafiyya: Reconsidering Salafism From the Perspective of Conceptual History,” IJMES 42 (2010): 369–89.

- ↑ Henri Lauzière, The Making of Salafism: Islamic Reform in the Twentieth Century (New York: Columbia University Press, 2016).

- ↑ Frank Griffel, “What Do We Mean By ‘Salafī’? Connecting Muḥammad ʿAbduh with Egypt’s Nūr Party in Islam’s Contemporary Intellectual History.” Die Welt des Islams 55 (2015): 186–220.

- ↑ Henri Lauzière, “What We Mean Versus What They Meant by "Salafi": A Reply to Frank Griffel” Die Welt des Islams 56 (2016): 89–96.

- ↑ Frank Griffel, “What is the Task of the Intellectual (Contemporary) Historian? – A Response to Henri Lauzière’s ‘Reply’.” Die Welt des Islams 56 (2016): 249–255, pp. 253–54.

- ↑ "Sheikh Zayed Book Award Announces Winners of its 18th Edition". sheikh zayed book award. Retrieved 2024-04-11.