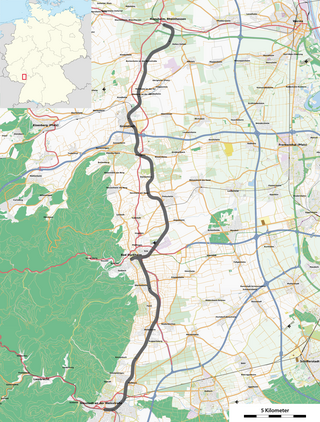

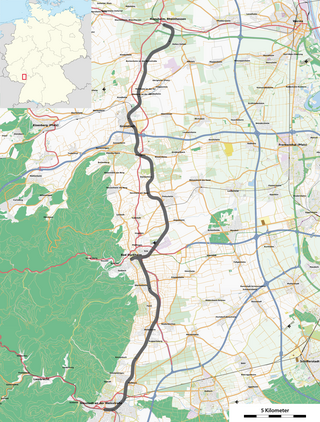

The Mannheim–Saarbrücken railway is a railway in the German states of Baden-Württemberg, Rhineland-Palatinate and the Saarland that runs through Ludwigshafen am Rhein, Neustadt an der Weinstraße, Kaiserslautern, Homburg and St. Ingbert It is the most important railway line that runs through the Palatinate. It serves both passenger and freight transport and carries international traffic.

The Palatine Northern Railway is a non-electrified single-track main line that connects Neustadt (Weinstr) Hbf with Monsheim in the German state of Rhineland-Palatinate. It was opened between 1865 and 1873 in three stages. With the replacement of the old Ludwigshafen terminus with the modern Ludwigshafen Hauptbahnhof through station in 1969, Bad Dürkheim station became the only station in the form of a terminus in the Palatinate region. Passenger services over the Grünstadt–Monsheim section were discontinued in 1984, but re-established in 1995.

Neustadt (Weinstr) Hauptbahnhof – called Neustadt a/d. Haardt until 1935 and from 1945 until 1950 – is the central station of in the city of Neustadt in the German state of Rhineland-Palatinate. In addition to the Hauptbahnhof, Rhine-Neckar S-Bahn services stop at Neustadt (Weinstr) Böbig halt (Haltepunkt). Mußbach station and Neustadt (Weinstr) halt, opened on 19 November 2013, are also located in Neustadt.

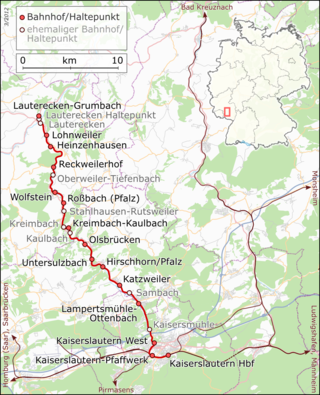

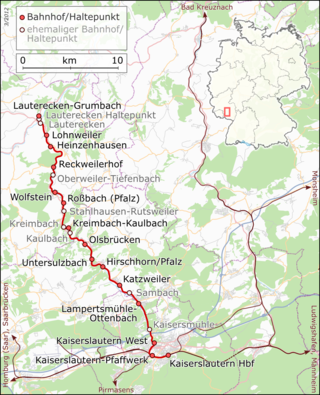

The Lauter Valley Railway is a branch line in the German state of Rhineland-Palatinate. It runs from Kaiserslautern along the Lauter river to Lauterecken. The railway, which was opened in 1883, has only regional importance. Deutsche Bundesbahn planned in the 1980s to close the line. Its existence has now been secured since the establishment of Deutsche Bahn. While freight traffic was discontinued in the 1990s, there has been growth in passenger demand.

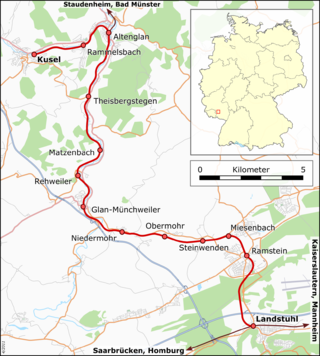

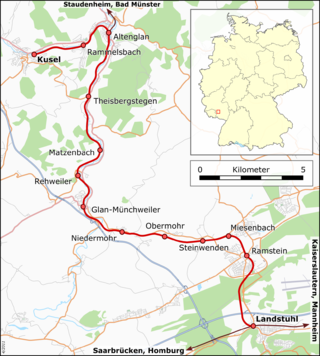

The Landstuhl–Kusel railway is a branch line in the German state of Rhineland-Palatinate, connecting the town of Kusel to the railway network. It was the first line built by the Palatine Northern Railway Company, which was then responsible within the Palatinate for all railway lines to the north of the Mannheim–Saarbrücken railway between Ludwigshafen and Bexbach and the first in the North Palatine Uplands. It was also the only railway in the western part of these uplands that was not threatened with closure at any time. The main purpose of its establishment was the development of the quarries in the area of the Altenglan area, leading to it being sometimes called the Steinbahn.

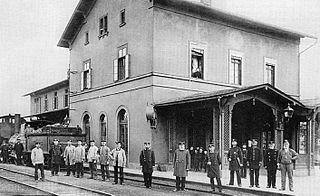

Kusel station is the station of the town of Kusel in the German state of Rhineland-Palatinate. It was opened on 22 September 1868 as the terminus of the Landstuhl–Kusel railway. It is classified by Deutsche Bahn as a category 6 station. The station is located in the network area of the Verkehrsverbund Rhein-Neckar. The address of the station is Bahnhofstraße 65.

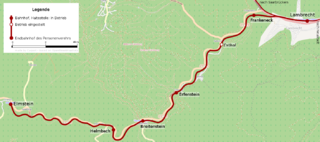

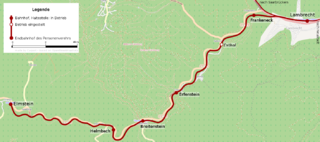

The Cuckoo Railway, in its early days the Elmstein Valley Railway, is a 12.97 kilometre long branch line in the central Palatine Forest, which runs through the region of Neustadt/Kaiserslautern from Lambrecht to Elmstein. It was built primarily to support the local forestry industry.

Landstuhl station is a station in the town of Landstuhl in the German state of Rhineland-Palatinate. Deutsche Bahn classifies it as belonging to station category 3 and has three platforms tracks. The station is located in the network of the Verkehrsverbund Rhein-Neckar (VRN) and belongs to fare zone 844.

The Kaiserslautern–Enkenbach railway is a single-track main line in the Western Palatinate. It runs within the area of the Verkehrsverbund Rhein-Neckar. It was built in 1875 to shorten the route for trains on the Alsenz Valley Railway (Alsenztalbahn) running to Kaiserslautern. In the following years, several express trains ran over this line. Passenger traffic was discontinued in 1987, but it was reactivated ten years later.

Enkenbach station is the only station in Enkenbach-Alsenborn in the German state of Rhineland-Palatinate. It has two platforms tracks and is located in the network of the Verkehrsverbund Rhein-Neckar and belongs to fare zone 828. Its address is Bahnhofstraße 2.

Hochspeyer station – originally officially Neuhochspeyer or Neu-Hochspeyer – is the station of the town of Hochspeyer in the German state of Rhineland-Palatinate. Deutsche Bahn classifies it as belonging to category 4 and it has four platform tracks. The station is located in the network of the Verkehrsverbund Rhein-Neckar and belongs to fare zone 100. Its address is Bahnhofstraße 1.

The Winden–Karlsruhe railway is a mainline railway in the German states of Baden-Württemberg and Rhineland-Palatinate, which in its present form has existed since 1938 and is electrified between Wörth and Karlsruhe. The current Winden–Wörth section was opened in 1864. A year later, the gap between the Rhine and the Maxau Railway (Maxaubahn), which had been opened in 1862, was closed. The route of the latter was changed during the relocation of the Karlsruhe Hauptbahnhof. New sections of the line were also built between Wörth and Mühlburg mainly in connection with the commissioning of a fixed bridge over the Rhine.

Wörth (Rhein) station—originally Wörth (Pfalz)—is the most important station of the town of Wörth am Rhein in the German state of Rhineland-Palatinate. Deutsche Bahn classifies it as a category 5 station and it has five platforms. The station is located in the area of the Karlsruher Verkehrsverbund and it belongs to fare zone 540. Since 2001, Verkehrsverbund Rhein-Neckar (VRN) tickets are also accepted for travel to or from the VRN area. The address of the station is Bahnhofstraße 44.

Winnweiler station is the station of the town of Winnweiler in the German state of Rhineland-Palatinate. Deutsche Bahn classifies it as a category 6 station and it has two platforms.

Weidenthal station is the station of the town of Weidenthal in the German state of Rhineland-Palatinate. It lies on the Mannheim–Saarbrücken railway, which essentially consists of the Pfälzischen Ludwigsbahn, which historically connected Ludwigshafen and Bexbach. It was opened on 25 August 1849, with the Kaiserslautern–Frankenstein section of the Ludwig Railway. Its entrance building is a protected monument.

Lambrecht (Pfalz) station is the station of the town of Lambrecht in the German state of Rhineland-Palatinate. Deutsche Bahn classifies it as belonging to category 4 and it has three platform tracks. The station is located in the network of the Verkehrsverbund Rhein-Neckar and belongs to fare zone 121. Its address is Bahnhofstraße 4.

Böhl-Iggelheim station is in the town of Böhl-Iggelheim in the German state of Rhineland-Palatinate. Deutsche Bahn classifies it as a category 5 station and it has two platforms. The station is located in the network of the Verkehrsverbund Rhein-Neckar. Its address is Am Bahnhofsplatz 4.

Limburgerhof station – called Mutterstadt until 1930 – is in the town of Limburgerhof in the German state of Rhineland-Palatinate. Deutsche Bahn classifies it as a category 4 station and it has two platform tracks and two through tracks. The station is located in the network of the Verkehrsverbund Rhein-Neckar and belongs to fare zone 123. Its address is Am Bahnhofsplatz 1.

Annweiler am Trifels station is the main station in the town of Annweiler am Trifels in the German state of Rhineland-Palatinate. Deutsche Bahn classifies it as a category 5 station and it has three platform tracks. The station is located in the network of the Verkehrsverbund Rhein-Neckar and belongs to fare zones 181 and 191. Since 2002, Annweiler has also been part of the area served by the Karlsruher Verkehrsverbund using tickets at a transitional rate. Annweiler was always the most important station between Landau (Pfalz) Hbf and Pirmasens Nord and it used to be served by long-distance services.

The Heiligenberg Tunnel is the longest of a total of twelve tunnels on the Mannheim-Saarbrücken railway and the longest in the Palatinate. The tunnel crosses the Palatine Watershed in the German state of Rhineland-Palatinate. It was originally built for a single track, but a second track was built a few years later.