The Reichskonkordat is a treaty negotiated between the Vatican and the emergent Nazi Germany. It was signed on 20 July 1933 by Cardinal Secretary of State Eugenio Pacelli, who later became Pope Pius XII, on behalf of Pope Pius XI and Vice Chancellor Franz von Papen on behalf of President Paul von Hindenburg and the German government. It was ratified 10 September 1933 and it remains in force to this day. The treaty guarantees the rights of the Catholic Church in Germany. When bishops take office, Article 16 states they are required to take an oath of loyalty to the Governor or President of the German Reich established according to the constitution. The treaty also requires all clergy to abstain from working in and for political parties. Nazi breaches of the agreement began after it had been signed and intensified afterwards. The Church protested, including in the 1937 Mit brennender Sorge encyclical of Pope Pius XI. The Nazis planned to eliminate the Church's influence by restricting its organizations to purely religious activities.

Mit brennender Sorge is an encyclical of Pope Pius XI, issued during the Nazi era on 10 March 1937. Written in German, not the usual Latin, it was smuggled into Germany for fear of censorship and was read from the pulpits of all German Catholic churches on one of the Church's busiest Sundays, Palm Sunday.

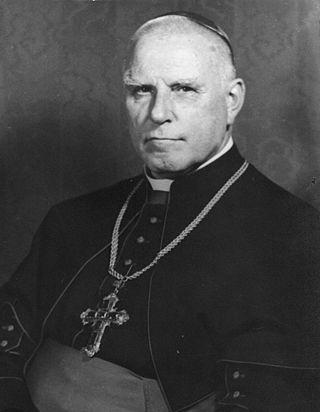

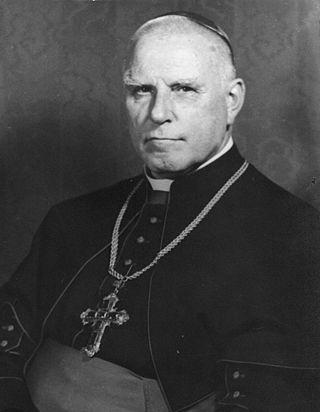

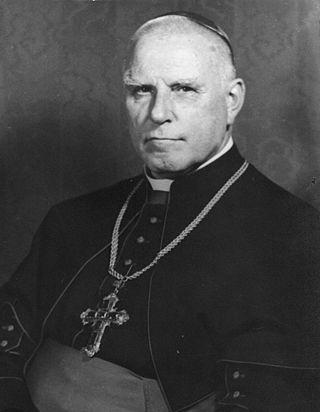

Clemens Augustinus Emmanuel Joseph Pius Anthonius Hubertus Marie Graf von Galen, better known as Clemens August Graf von Galen, was a German count, Bishop of Münster, and cardinal of the Catholic Church. During World War II, Galen led Catholic protests against Nazi euthanasia and denounced Gestapo lawlessness and the persecution of the Church in Nazi Germany. He was appointed a cardinal by Pope Pius XII in 1946, shortly before his death, and was beatified by Pope Benedict XVI in 2005.

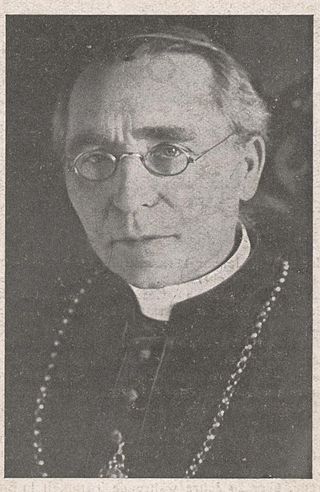

Ludwig Kaas was a German Roman Catholic priest and politician of the Centre Party during the Weimar Republic. He was instrumental in brokering the Reichskonkordat between the Holy See and the German Reich.

Nazi Germany was an overwhelmingly Christian nation. A census in May 1939, six years into the Nazi era and a year following the annexations of Austria and Czechoslovakia into Germany, indicates that 54% of the population considered itself Protestant, 41% considered itself Catholic, 3.5% self-identified as Gottgläubig, and 1.5% as "atheist". Protestants were over-represented in the Nazi Party's membership and electorate, and Catholics were under-represented.

The Catholic Church in Germany or Roman Catholic Church in Germany is part of the worldwide Roman Catholic Church in communion with the Pope, assisted by the Roman Curia, and with the German bishops. The current "Speaker" of the episcopal conference is Georg Bätzing, Bishop of the Roman Catholic Diocese of Limburg. It is divided into 27 dioceses, 7 of them with the rank of metropolitan sees.

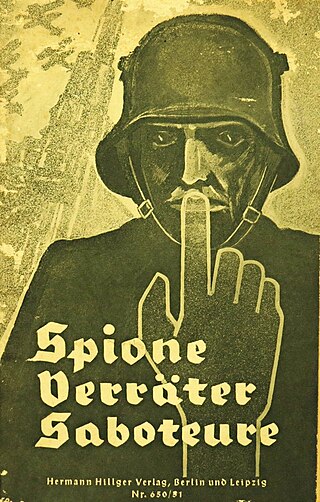

The German resistance to Nazism included unarmed and armed opposition and disobedience to the Nazi regime by various movements, groups and individuals by various means, from attempts to assassinate Adolf Hitler or to overthrow his regime, defection to the enemies of the Third Reich and sabotage against the German Army and the apparatus of repression and attempts to organize armed struggle, to open protests, rescue of persecuted persons, dissidence and "everyday resistance".

Holocaust victims were people targeted by the government of Nazi Germany based on their ethnicity, religion, political beliefs, disability or sexual orientation. The institutionalized practice by the Nazis of singling out and persecuting people resulted in the Holocaust, which began with legalized social discrimination against specific groups, involuntary hospitalization, euthanasia, and forced sterilization of persons considered physically or mentally unfit for society. The vast majority of the Nazi regime's victims were Jews, Sinti-Roma peoples, and Slavs but victims also encompassed people identified as social outsiders in the Nazi worldview, such as homosexuals, and political enemies. Nazi persecution escalated during World War II and included: non-judicial incarceration, confiscation of property, forced labor, sexual slavery, death through overwork, human experimentation, undernourishment, and execution through a variety of methods. For specified groups like the Jews, genocide was the Nazis' primary goal.

Austria was part of Nazi Germany from 13 March 1938 until 27 April 1945, when Allied-occupied Austria declared independence from Nazi Germany.

Kirchenkampf is a German term which pertains to the situation of the Christian churches in Germany during the Nazi period (1933–1945). Sometimes used ambiguously, the term may refer to one or more of the following different "church struggles":

- The internal dispute within German Protestantism between the German Christians and the Confessing Church over control of the Protestant churches;

- The tensions between the Nazi regime and the Protestant church bodies; and

- The tensions between the Nazi regime and the Catholic Church.

Catholic bishops in Nazi Germany differed in their responses to the rise of Nazi Germany, World War II, and the Holocaust during the years 1933–1945. In the 1930s, the Episcopate of the Catholic Church of Germany comprised 6 Archbishops and 19 bishops while German Catholics comprised around one third of the population of Germany served by 20,000 priests. In the lead up to the 1933 Nazi takeover, German Catholic leaders were outspoken in their criticism of Nazism. Following the Nazi takeover, the Catholic Church sought an accord with the Government, was pressured to conform, and faced persecution. The regime had flagrant disregard for the Reich concordat with the Holy See, and the episcopate had various disagreements with the Nazi government, but it never declared an official sanction of the various attempts to overthrow the Hitler regime. Ian Kershaw wrote that the churches "engaged in a bitter war of attrition with the regime, receiving the demonstrative backing of millions of churchgoers. Applause for Church leaders whenever they appeared in public, swollen attendances at events such as Corpus Christi Day processions, and packed church services were outward signs of the struggle of ... especially of the Catholic Church - against Nazi oppression". While the Church ultimately failed to protect its youth organisations and schools, it did have some successes in mobilizing public opinion to alter government policies.

Popes Pius XI (1922–1939) and Pius XII (1939–1958) led the Catholic Church during the rise and fall of Nazi Germany. Around a third of Germans were Catholic in the 1930s, most of them lived in Southern Germany; Protestants dominated the north. The Catholic Church in Germany opposed the NSDAP, and in the 1933 elections, the proportion of Catholics who voted for the Nazi Party was lower than the national average. Nevertheless, the Catholic-aligned Centre Party voted for the Enabling Act of 1933, which gave Adolf Hitler additional domestic powers to suppress political opponents as Chancellor of Germany. President Paul Von Hindenburg continued to serve as Commander and Chief and he also continued to be responsible for the negotiation of international treaties until his death on 2 August 1934.

During the pontificate of Pope Pius XI (1922–1939), the Weimar Republic transitioned into Nazi Germany. In 1933, the ailing President von Hindenburg appointed Adolf Hitler as Chancellor of Germany in a Coalition Cabinet, and the Holy See concluded the Reich concordat treaty with the still nominally functioning Weimar state later that year. Hoping to secure the rights of the Church in Germany, the Church agreed to a requirement that clergy cease to participate in politics. The Hitler regime routinely violated the treaty, and launched a persecution of the Catholic Church in Germany.

During the German occupation of Poland (1939–1945), the Nazis brutally suppressed the Catholic Church in Poland, most severely in German-occupied areas of Poland. Thousands of churches and monasteries were systematically closed, seized or destroyed. As a result, many works of religious art and objects were permanently lost.

Catholic resistance to Nazi Germany was a component of German resistance to Nazism and of Resistance during World War II. The role of the Catholic Church during the Nazi years remains a matter of much contention. From the outset of Nazi rule in 1933, issues emerged which brought the church into conflict with the regime and persecution of the church led Pope Pius XI to denounce the policies of the Nazi Government in the 1937 papal encyclical Mit brennender Sorge. His successor Pius XII faced the war years and provided intelligence to the Allies. Catholics fought on both sides in World War II and neither the Catholic nor Protestant churches as institutions were prepared to openly oppose the Nazi State.

During the Second World War, the Roman Catholic Church protested against Aktion T4, the Nazi involuntary euthanasia programme under which 300,000 disabled people were murdered. The protests formed one of the most significant public acts of Catholic resistance to Nazism undertaken within Germany. The "euthanasia" programme began in 1939, and ultimately resulted in the murder of more than 70,000 people who were deemed senile, mentally handicapped, mentally ill, epileptics, cripples, children with Down's Syndrome, or people with similar afflictions. The murders involved interference in Church welfare institutions, and awareness of the murderous programme became widespread. Church leaders who opposed it – chiefly the Catholic Bishop Clemens August von Galen of Münster and Protestant Bishop Theophil Wurm – were therefore able to rouse widespread public opposition.

Nazi ideology could not accept an autonomous establishment whose legitimacy did not spring from the government. It desired the subordination of the church to the state. To many Nazis, Catholics were suspected of insufficient patriotism, or even of disloyalty to the Fatherland, and of serving the interests of "sinister alien forces". Nazi radicals also disdained the Semitic origins of Jesus and the Christian religion. Although the broader membership of the Nazi Party after 1933 came to include many Catholics, aggressive anti-church radicals like Alfred Rosenberg, Martin Bormann, and Heinrich Himmler saw the kirchenkampf campaign against the churches as a priority concern, and anti-church and anti-clerical sentiments were strong among grassroots party activists.

The Roman Catholic Church suffered persecution in Nazi Germany. The Nazis claimed jurisdiction over all collective and social activity. Clergy were watched closely, and frequently denounced, arrested and sent to Nazi concentration camps. Welfare institutions were interfered with or transferred to state control. Catholic schools, press, trade unions, political parties and youth leagues were eradicated. Anti-Catholic propaganda and "morality" trials were staged. Monasteries and convents were targeted for expropriation. Prominent Catholic lay leaders were murdered, and thousands of Catholic activists were arrested.

Several Catholic countries and populations fell under Nazi domination during the period of the Second World War (1939–1945), and ordinary Catholics fought on both sides of the conflict. Despite efforts to protect its rights within Germany under a 1933 Reichskonkordat treaty, the Church in Germany had faced persecution in the years since Adolf Hitler had seized power, and Pope Pius XI accused the Nazi government of sowing 'fundamental hostility to Christ and his Church'. The concordat has been described by some as giving moral legitimacy to the Nazi regime soon after Hitler had acquired quasi-dictatorial powers through the Enabling Act of 1933, an Act itself facilitated through the support of the Catholic Centre Party. Pius XII became Pope on the eve of war and lobbied world leaders to prevent the outbreak of conflict. His first encyclical, Summi Pontificatus, called the invasion of Poland an "hour of darkness". He affirmed the policy of Vatican neutrality, but maintained links to the German Resistance. Despite being the only world leader to publicly and specifically denounce Nazi crimes against Jews in his 1942 Christmas Address, controversy surrounding his apparent reluctance to speak frequently and in even more explicit terms about Nazi crimes continues. He used diplomacy to aid war victims, lobbied for peace, shared intelligence with the Allies, and employed Vatican Radio and other media to speak out against atrocities like race murders. In Mystici corporis Christi (1943) he denounced the murder of the handicapped. A denunciation from German bishops of the murder of the "innocent and defenceless", including "people of a foreign race or descent", followed.

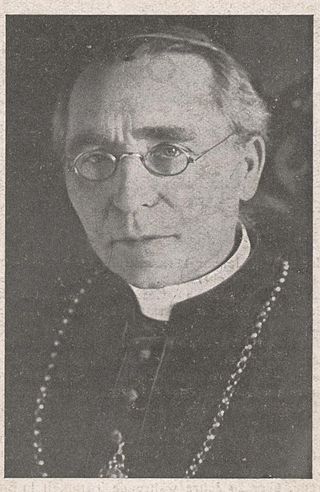

Caspar Klein was a Catholic Archbishop of Paderborn, Germany, during the Nazi era.