Related Research Articles

This is a list of notable events in the history of LGBT rights that took place in the year 1981.

This is a list of notable events in the history of LGBT rights that took place in the year 1992.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) rights in Cuba have significantly varied throughout modern history. Cuba is now considered generally progressive, with vast improvements in the 21st century for such rights. Following the 2022 Cuban Family Code referendum, there is legal recognition of the right to marriage, unions between people of the same sex, same-sex adoption and non-commercial surrogacy as part of one of the most progressive Family Codes in Latin America. Until the 1990s, the LGBT community was marginalized on the basis of heteronormativity, traditional gender roles, politics and strict criteria for moralism. It was not until the 21st century that the attitudes and acceptance towards LGBT people changed to be more tolerant.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people living in Lebanon may face discrimination and legal difficulties not experienced by non-LGBT residents, although they have more freedom than in other parts of the Arab world. Various courts have ruled that Article 534 of the Lebanese Penal Code, which prohibits having sexual relations that "contradict the laws of nature", should not be used to arrest LGBT people. Nonetheless, the law is still being used to harass and persecute LGBT people through occasional police arrests, in which detainees are sometimes subject to intrusive physical examinations.

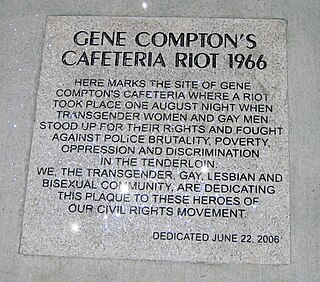

The Compton's Cafeteria riot occurred in August 1966 in the Tenderloin district of San Francisco. The riot was a response to the violent and constant police harassment of drag queens and trans people, particularly trans women. The incident was one of the first LGBT-related riots in United States history, preceding the more famous 1969 Stonewall riots in New York City. It marked the beginning of transgender activism in San Francisco.

This is a timeline of notable events in the history of the lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender (LGBT) community in Canada. For a broad overview of LGBT history in Canada see LGBT history in Canada.

This is a list of notable events in the history of LGBT rights that took place in the 1960s.

The Black Cat Tavern is an LGBT historic site located in the Silver Lake neighborhood of Los Angeles, California. In 1967, it was the site of one of the first demonstrations in the United States protesting police brutality against LGBT people, preceding the Stonewall riots by over two years.

The U.S. state of New York has generally been seen as socially liberal in regard to lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) rights. LGBT travel guide Queer in the World states, "The fabulosity of Gay New York is unrivaled on Earth, and queer culture seeps into every corner of its five boroughs". The advocacy movement for LGBT rights in the state has been dated as far back as 1969 during the Stonewall riots in New York City. Same-sex sexual activity between consenting adults has been legal since the New York v. Onofre case in 1980. Same-sex marriage has been legal statewide since 2011, with some cities recognizing domestic partnerships between same-sex couples since 1998. Discrimination protections in credit, housing, employment, education, and public accommodation have explicitly included sexual orientation since 2003 and gender identity or expression since 2019. Transgender people in the state legally do not have to undergo sex reassignment surgery to change their sex or gender on official documents since 2014. In addition, both conversion therapy on minors and the gay and trans panic defense have been banned since 2019. Since 2021, commercial surrogacy has been legally available within New York State.

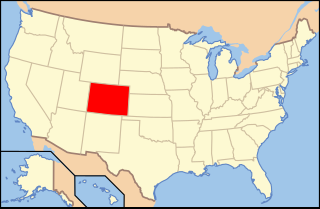

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people in the U.S. state of Colorado enjoy the same rights as non-LGBT people. Same-sex sexual activity has been legal in Colorado since 1972. Same-sex marriage has been recognized since October 2014, and the state enacted civil unions in 2013, which provide some of the rights and benefits of marriage. State law also prohibits discrimination on account of sexual orientation and gender identity in employment, housing and public accommodations and the use of conversion therapy on minors. In July 2020, Colorado became the 11th US state to abolish the gay panic defense.

LGBT history in the United States spans the contributions and struggles of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people, as well as the LGBT social movements they have built.

This article concerns LGBT history in Florida.

The state of North Dakota has improved in its treatment of lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender residents in the late 1990s and into the 21st Century, when the LGBT community began to openly establish events, organizations and outlets for fellow LGBT residents and allies, and increase in political and community awareness.

The Cooper Do-nuts Riot was an alleged uprising in reaction to police harassment of LGBT people at a 24-hour donut cafe in Los Angeles in the 1960s. Whether the riot actually happened, the date, location and whether or not the cafe was a branch of the Cooper chain are all disputed, and there is a lack of contemporary documentary evidence, with the Los Angeles Police Department (LAPD) stating that any records of such event would have been purged years ago.

The Right to Privacy Committee (RTPC) was a Canadian organization located in Toronto, and was one of the city's largest and most active advocacy groups during the 1980s, a time of strained police-minority relations. The group focused on the Toronto Police Service's harassment of gays and infringement of privacy rights, and challenged police authority to search gay premises and seize materials. At the time of the 1981 bathhouse raids, RTPC was Canada's largest gay rights group with a mailing and volunteer list of 1,200 names. People associated with the RTPC include Michael Laking, Rev. Brent Hawkes, John Alan Lee, Dennis Findlay, Tom Warner, and George W. Smith.

Bengaluru Namma Pride March is a queer pride march that is held annually in the city of Bengaluru in Karnataka, India, since 2008. The march is organised by a coalition called Coalition for Sex Workers and Sexuality Minority Rights (CSMR). The pride march is preceded by a month of queer related events and activities

The Village Station police raid was a police raid that targeted the Village Station, a gay bar in Dallas, Texas, United States. The raid occurred on October 25, 1979, and saw several bar patrons arrested for public lewdness while performing a bunny hop dance. The raid and the subsequent court cases involving those arrested are considered an important moment in the LGBT history of Dallas, with the impact it had on the city compared to that of the Stonewall riots of 1969.

The Fun Lounge police raid was a 1964 police raid that targeted Louie's Fun Lounge, a gay bar near Chicago, Illinois, United States. The raid led to the arrest of over 100 individuals and is considered a notable moment in the LGBT history of the area.

On November 19–20, 2022, an anti-LGBT-motivated mass shooting occurred at Club Q, a gay bar in Colorado Springs, Colorado, United States. Five people were murdered, and 25 others were injured, 19 of them by gunfire. The shooter, 22-year-old Anderson Lee Aldrich, was also injured while being restrained, and was taken to a local hospital. Aldrich was charged and remanded in custody. On June 26, 2023, Aldrich pled guilty to the shooting and was sentenced to five consecutive terms of life in prison without the possibility of parole, plus 2,211 years. On January 16, 2024, Aldrich was additionally charged with 50 federal hate crimes in connection with the shooting.

The Center on Colfax is a LGBTQ community center in Denver, Colorado. The nonprofit provides programs and services to the queer community including mental health support, historical preservation, and community building.

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Marcus, Aaron. "In Silence, Ignorance Thrives". History Colorado.

- 1 2 3 4 Beaty, Kevin (December 5, 2022). "When the cops weren't around, gay bars like downtown's Court Jester offered safe space in a hostile city". Denverite.

- 1 2 "Queer Spaces in Denver 1870-1980" (PDF). Historic Denver.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Gerash, Gerald. "THE ORIGINS OF THE CENTER – HOW AND WHY IT CAME ABOUT". Denver Gay Revolt.

- 1 2 "A Brief History of LGBT Rights in Colorado". Law Week Colorado.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Bindel, Paul (December 16, 2015). "In the beginning..." Out Front Magazine.

- ↑ Sylvestre, Berlin (August 20, 2014). "A Brief LGBT History of Colorado". Out Front Magazine.

- 1 2 Nash, Phil (October 18, 2023). "Denver's Stonewall: Commemorating a Half-Century of Fighting Back". Westword.

- ↑ Gerash, Gerald. "The Gay Coalition of Denver Film Footage". Youtube. History Colorado.