Section 377 is a British colonial penal code that criminalized all sexual acts "against the order of nature". The law was used to prosecute people engaging in oral and anal sex along with homosexual activity. As per a Supreme Court Judgement since 2018, the Indian Penal Code Section 377 is used to convict non-consensual sexual activities among homosexuals with a minimum of ten years’ imprisonment extended to life imprisonment. It has been used to criminalize third gender people, such as the apwint in Myanmar. In 2018, then British Prime Minister Theresa May acknowledged how the legacies of such British colonial anti-sodomy laws continue to persist today in the form of discrimination, violence, and even death.

The legal age of consent for sexual activity varies by jurisdiction across Asia. The specific activity engaged in or the gender of participants can also be relevant factors. Below is a discussion of the various laws dealing with this subject. The highlighted age refers to an age at or above which an individual can engage in unfettered sexual relations with another who is also at or above that age. Other variables, such as homosexual relations or close in age exceptions, may exist, and are noted when relevant.

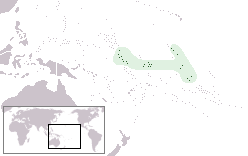

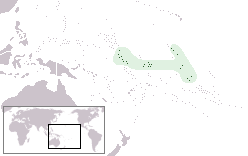

The ages of consent for sexual activity vary from age 15 to 18 across Australia, New Zealand and other parts of Oceania. The specific activity and the gender of its participants is also addressed by the law. The minimum age is the age at or above which an individual can engage in unfettered sexual relations with another person of minimum age. Close in age exceptions may exist and are noted where applicable. In Vanuatu the homosexual age of consent is set higher at 18, while the heterosexual age of consent is 15. Same sex sexual activity is illegal at any age for males in Papua New Guinea, Kiribati, Samoa, Niue, Tonga and Tuvalu; it is outlawed for both men and women in the Solomon Islands. In all other places the age of consent is independent of sexual orientation or gender.

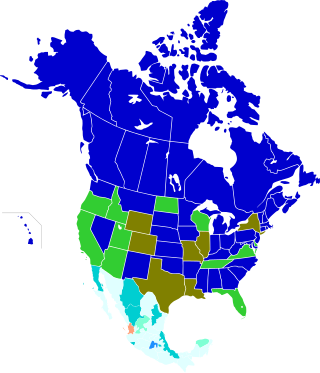

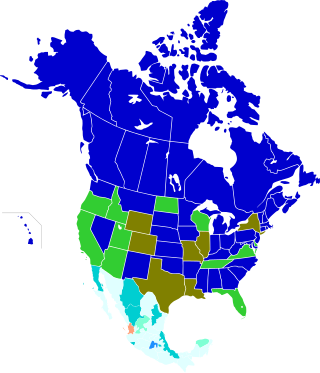

In North America, the legal age of consent relating to sexual activity varies by jurisdiction.

The age of consent in Africa for sexual activity varies by jurisdiction across the continent, codified in laws which may also stipulate the specific activities that are permitted or the gender of participants for different ages. Other variables may exist, such as close-in-age exemptions.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people in Trinidad and Tobago face legal challenges not experienced by non-LGBTQ residents. Households headed by same-sex couples are not eligible for the same rights and benefits as that of opposite-sex couples.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people in Dominica face legal challenges not experienced by non-LGBTQ residents. Homosexuality has been legal since 2024, when the High Court struck down the country's colonial-era sodomy law. Dominica provides no recognition to same-sex unions, whether in the form of marriage or civil unions, and no law prohibits discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation or gender identity.

National Coalition for Gay and Lesbian Equality and Another v Minister of Justice and Others is a decision of the Constitutional Court of South Africa which struck down the laws prohibiting consensual sexual activities between men. Basing its decision on the Bill of Rights in the Constitution – and in particular its explicit prohibition of discrimination based on sexual orientation – the court unanimously ruled that the crime of sodomy, as well as various other related provisions of the criminal law, were unconstitutional and therefore invalid.

In common law jurisdictions, statutory rape is nonforcible sexual activity in which one of the individuals is below the age of consent. Although it usually refers to adults engaging in sexual contact with minors under the age of consent, it is a generic term, and very few jurisdictions use the actual term statutory rape in the language of statutes. In statutory rape, overt force or threat is usually not present. Statutory rape laws presume coercion because a minor or mentally disabled adult is legally incapable of giving consent to the act.

A sodomy law is a law that defines certain sexual acts as crimes. The precise sexual acts meant by the term sodomy are rarely spelled out in the law, but are typically understood and defined by many courts and jurisdictions to include any or all forms of sexual acts that are illegal, illicit, unlawful, unnatural and immoral. Sodomy typically includes anal sex, oral sex, manual sex, and bestiality. In practice, sodomy laws have rarely been enforced to target against sexual activities between individuals of the opposite sex, and have mostly been used to target against sexual activities between individuals of the same sex.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) persons in Antigua and Barbuda may face legal challenges not experienced by non-LGBTQ citizens.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBTQ) persons in Belize face legal challenges not experienced by non-LGBT citizens, although attitudes have been changing in recent years. Same-sex sexual activity was decriminalized in Belize in 2016, when the Supreme Court declared Belize's anti-sodomy law unconstitutional. Belize's constitution prohibits discrimination on the basis of sex, which Belizean courts have interpreted to include sexual orientation.

Leung TC William Roy v Secretary for Justice is a leading Hong Kong High Court judicial review case on the equal protection on sexual orientation and the law of standing in Hong Kong. Particularly, the Court sets up a precedent case prohibiting unjustified differential treatments based upon one's sexual orientation.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people in Kiribati face legal challenges not experienced by non-LGBT residents. Male homosexuality is illegal in Kiribati with a penalty of up to 14 years in prison, but the law is not enforced. Female homosexuality is legal, but lesbians may face violence and discrimination. Despite this, employment discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation has been prohibited since 2015.

The Criminal Law Amendment Act, 2007 is an act of the Parliament of South Africa that reformed and codified the law relating to sex offences. It repealed various common law crimes and replaced them with statutory crimes defined on a gender-neutral basis. It expanded the definition of rape, previously limited to vaginal sex, to include all non-consensual penetration; and it equalised the age of consent for heterosexual and homosexual sex at 16. The act provides various services to the victims of sexual offences, including free post-exposure prophylaxis for HIV, and the ability to obtain a court order to compel HIV testing of the alleged offender. It also created the National Register for Sex Offenders, which records the details of those convicted of sexual offences against children or people who are mentally disabled.

National Coalition for Gay and Lesbian Equality and Others v Minister of Home Affairs and Others, [1999] ZACC 17, is a 1999 decision of the Constitutional Court of South Africa which extended to same-sex partners the same benefits granted to spouses in the issuing of immigration permits. It was the first Constitutional Court case to deal with the recognition of same-sex partnerships, and also the first case in which a South African court adopted the remedy of "reading in" to correct an unconstitutional law. The case is of particular importance in the areas of civil procedure, immigration, and constitutional law and litigation.

This is a timeline of notable events in the history of lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender people in South Africa.

Article 365 of the Sri Lankan Penal Code criminalizes "carnal intercourse against the order of nature" and provides for a penalty of up to ten years in prison.

Orozco v Attorney General (2016) 90 WIR 161, also known as Orozco v AG, the Orozco case, or the UNIBAM case, was a landmark case heard by the Supreme Court of Belize, which held that a long-standing buggery statute breached constitutional rights to dignity, equality before the law, freedom of expression, privacy, and non-discrimination on grounds of sex, and which declared the statute null and void to the applicable extent. The decision decriminalised consensual same-sex intercourse for the first time in 127 years, and established that the constitutional right to non-discrimination on grounds of sex extended to sexual orientation.

S v Jordan and Others is a decision of the Constitutional Court of South Africa which confirmed the constitutionality of statutory prohibitions on brothel-keeping and prostitution. It was handed down on 9 October 2002 with a majority judgment by Justice Sandile Ngcobo.