The Reign of Terror, or The Terror, refers to a period during the French Revolution after the First French Republic was established.

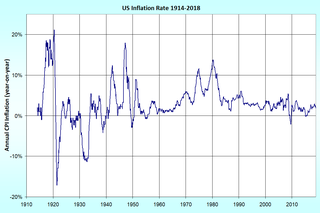

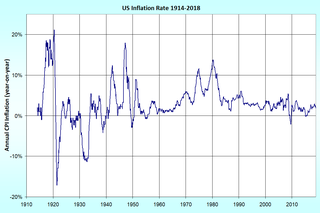

In economics, inflation is a sustained increase in the general price level of goods and services in an economy over a period of time. When the general price level rises, each unit of currency buys fewer goods and services; consequently, inflation reflects a reduction in the purchasing power per unit of money – a loss of real value in the medium of exchange and unit of account within the economy. The measure of inflation is the inflation rate, the annualized percentage change in a general price index, usually the consumer price index, over time. The opposite of inflation is deflation.

In the history of France, the First Republic, officially the French Republic, was founded on 22 September 1792 during the French Revolution. The First Republic lasted until the declaration of the First Empire in 1804 under Napoleon, although the form of the government changed several times. This period was characterized by the fall of the monarchy, the establishment of the National Convention and the Reign of Terror, the Thermidorian Reaction and the founding of the Directory, and, finally, the creation of the Consulate and Napoleon's rise to power.

Jacques Necker was a banker of Genevan origin who became a finance minister for Louis XVI and a French statesman. Necker played a key role in French history before and during the first period of the French Revolution.

The Society of the Friends of the Constitution, after 1792 renamed Society of the Jacobins, Friends of Freedom and Equality, commonly known as the Jacobin Club or simply the Jacobins, became the most influential political club during the French Revolution of 1789 and following. The period of their political ascendency is known as the Reign of Terror, during which time tens of thousands were put on trial and executed in France, many for political crimes.

Pierre Gaspard Chaumette was a French politician of the Revolutionary period who served as the president of the Paris Commune and played a leading role in the establishment of the Reign of Terror. He was one of the ultra-radical enragés of the revolution, an ardent critic of Christianity who was one of the leaders of the dechristianization of France. His radical positions resulted in his alienation from Maximilien Robespierre, and he was arrested on charges of being a counterrevolutionary and executed.

The Mountain was a political group during the French Revolution, whose members called the Montagnards sat on the highest benches in the National Assembly.

An assignat was a type of a monetary instrument used during the time of the French Revolution, and the French Revolutionary Wars.

Jacques René Hébert was a French journalist, and the founder and editor of the extreme radical newspaper Le Père Duchesne during the French Revolution. He was a leader of the French Revolution and had thousands of followers as the Hébertists ; he himself is sometimes called Père Duchesne, after his newspaper.

The causes of the French Revolution can be attributed to several intertwining factors:

Incomes policies in economics are economy-wide wage and price controls, most commonly instituted as a response to inflation, and usually seeking to establish wages and prices below free market level.

The Revolutionary Tribunal was a court instituted by the National Convention during the French Revolution for the trial of political offenders. It eventually became one of the most powerful engines of the Reign of Terror.

Mandats territoriaux were paper bank notes issued as currency by the French Directory in 1796 to replace the assignats which had become virtually worthless. They were land-warrants supposedly redeemable in the lands confiscated from royalty, the clergy and the church after the outbreak of the French Revolution in 1789. In February 1796, 800,000,000 francs of mandats were issued as legal tender to replace the 24,000,000,000 francs of assignats then outstanding. In all about 2,500,000,000 francs of mandats were issued. They were heavily counterfeited and their value depreciated rapidly within six months. In February 1797, they lost their legal tender quality and by May were worth virtually nothing.

The biens nationaux were properties confiscated during the French Revolution from the Catholic Church, the monarchy, émigrés, and suspected counter-revolutionaries for "the good of the nation".

Historians since the late 20th century have debated how women shared in the French Revolution and what long-term impact it had on French women. Women had no political rights in pre-Revolutionary France; they were considered "passive" citizens, forced to rely on men to determine what was best for them. That changed dramatically in theory as there seemingly were great advances in feminism. Feminism emerged in Paris as part of a broad demand for social and political reform. The women demanded equality to men and then moved on to a demand for the end of male domination. Their chief vehicle for agitation were pamphlets and women's clubs, especially the Society of Revolutionary Republican Women. However, the Jacobin (radical) element in power abolished all the women's clubs in October 1793 and arrested their leaders. The movement was crushed. Devance explains the decision in terms of the emphasis on masculinity in wartime, Marie Antoinette's bad reputation for feminine interference in state affairs, and traditional male supremacy. A decade later the Napoleonic Code confirmed and perpetuated women's second-class status.