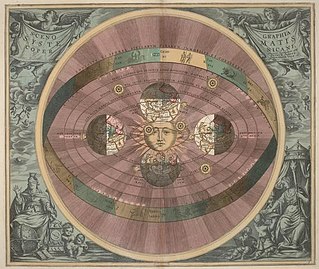

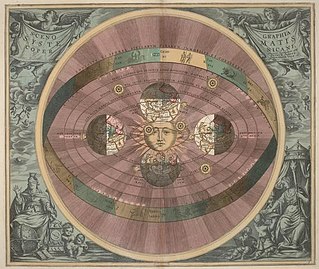

Heliocentrism is a superseded astronomical model in which the Earth and planets revolve around the Sun at the center of the universe. Historically, heliocentrism was opposed to geocentrism, which placed the Earth at the center. The notion that the Earth revolves around the Sun had been proposed as early as the 3rd century BC by Aristarchus of Samos, who had been influenced by a concept presented by Philolaus of Croton. In the 5th century BC the Greek philosophers Philolaus and Hicetas had the thought on different occasions that the Earth was spherical and revolving around a "mystical" central fire, and that this fire regulated the universe. In medieval Europe, however, Aristarchus' heliocentrism attracted little attention—possibly because of the loss of scientific works of the Hellenistic period.

ʿAbu al-Ḥasan Alāʾ al‐Dīn bin Alī bin Ibrāhīm bin Muhammad bin al-Matam al-Ansari, known as Ibn al-Shatir or Ibn ash-Shatir was an Arab astronomer, mathematician and engineer. He worked as muwaqqit in the Umayyad Mosque in Damascus and constructed a sundial for its minaret in 1371/72.

Al-Urdi was a medieval Syrian Arab astronomer and geometer.

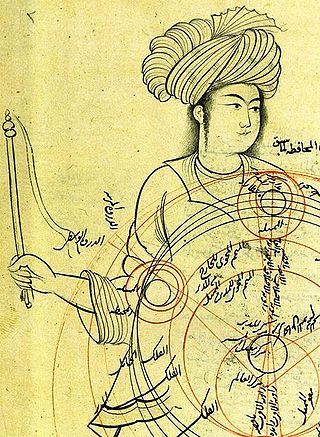

Qotb al-Din Mahmoud b. Zia al-Din Mas'ud b. Mosleh Shirazi was a 13th-century Persian polymath and poet who made contributions to astronomy, mathematics, medicine, physics, music theory, philosophy and Sufism.

This is a timeline of astronomy. It covers ancient, medieval, Renaissance-era, and finally modern astronomy.

The Copernican Revolution was the paradigm shift from the Ptolemaic model of the heavens, which described the cosmos as having Earth stationary at the center of the universe, to the heliocentric model with the Sun at the center of the Solar System. This revolution consisted of two phases; the first being extremely mathematical in nature and the second phase starting in 1610 with the publication of a pamphlet by Galileo. Beginning with the 1543 publication of Nicolaus Copernicus’s De revolutionibus orbium coelestium, contributions to the “revolution” continued until finally ending with Isaac Newton’s work over a century later.

Medieval Islamic astronomy comprises the astronomical developments made in the Islamic world, particularly during the Islamic Golden Age, and mostly written in the Arabic language. These developments mostly took place in the Middle East, Central Asia, Al-Andalus, and North Africa, and later in the Far East and India. It closely parallels the genesis of other Islamic sciences in its assimilation of foreign material and the amalgamation of the disparate elements of that material to create a science with Islamic characteristics. These included Greek, Sassanid, and Indian works in particular, which were translated and built upon.

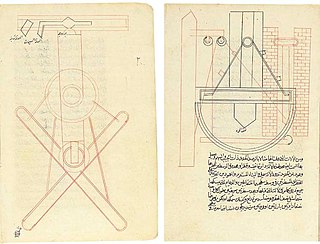

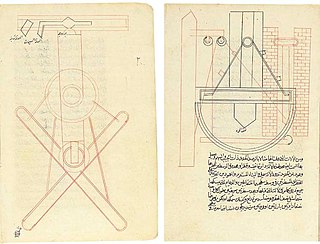

The Tusi couple is a mathematical device in which a small circle rotates inside a larger circle twice the diameter of the smaller circle. Rotations of the circles cause a point on the circumference of the smaller circle to oscillate back and forth in linear motion along a diameter of the larger circle. The Tusi couple is a 2-cusped hypocycloid.

Islamic cosmology is the cosmology of Islamic societies. Islamic cosmology is not a single unitary system, but is inclusive of a number of cosmological systems, including Quranic cosmology, the cosmology of the Hadith collections, as well as those of Islamic astronomy and astrology. Broadly, cosmological conceptions themselves can be divided into thought concerning the physical structure of the cosmos (cosmography) and the origins of the cosmos (cosmogony).

Some medieval Muslims took a keen interest in the study of astrology, partly because they considered the celestial bodies to be essential, partly because the dwellers of desert-regions often travelled at night, and relied upon knowledge of the constellations for guidance in their journeys.

The Maragheh observatory, also spelled Maragha, Maragah, Marageh, and Maraga, was an astronomical observatory established in the mid 13th century under the patronage of the Ilkhanid Hulagu and the directorship of Nasir al-Din al-Tusi, a Persian scientist and astronomer. The observatory is located on the west side of Maragheh, which is situated in today's East Azerbaijan Province of Iran. It was considered one of the most advanced scientific institutions in Eurasia because it was a center for many groundbreaking calculations in mathematics and astronomy. It housed a large collection of astronomical instruments and books and it served as an educational institution. It was also used as a model for the later Ulugh Beg Observatory in Samarkand, the Taqi al-Din observatory in Constantinople, and Jantar Mantar observatory in Jaipur.

Muḥyī al‐Milla wa al‐Dīn Yaḥyā Abū ʿAbdallāh ibn Muḥammad ibn Abī al‐Shukr al‐Maghribī al‐Andalusī, referred to in sources as Muhyi l'din, was an astronomer, astrologer and mathematician of the Islamic Golden Age. He belonged to the group of astronomers associated with the Maragheh observatory in the Ilkhanate, most notably Nasir al-Din al-Tusi. In astronomy, Muhyi l'din carried out a large‐scale project of systematic planetary observations, which led to the development of several new astronomical parameters.

Copernican heliocentrism is the astronomical model developed by Nicolaus Copernicus and published in 1543. This model positioned the Sun at the center of the Universe, motionless, with Earth and the other planets orbiting around it in circular paths, modified by epicycles, and at uniform speeds. The Copernican model displaced the geocentric model of Ptolemy that had prevailed for centuries, which had placed Earth at the center of the Universe.

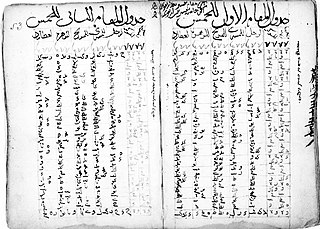

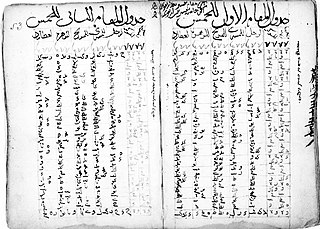

A zij is an Islamic astronomical book that tabulates parameters used for astronomical calculations of the positions of the sun, moon, stars, and planets.

Ala al-Dīn Ali ibn Muhammed, known as Ali Qushji was a Timurid theologian, jurist, astronomer, mathematician and physicist, who settled in the Ottoman Empire some time before 1472. As a disciple of Ulugh Beg, he is best known for the development of astronomical physics independent from natural philosophy, and for providing empirical evidence for the Earth's rotation in his treatise, Concerning the Supposed Dependence of Astronomy upon Philosophy. In addition to his contributions to Ulugh Beg's famous work Zij-i-Sultani and to the founding of Sahn-ı Seman Medrese, one of the first centers for the study of various traditional Islamic sciences in the Ottoman Empire, Ali Kuşçu was also the author of several scientific works and textbooks on astronomy.

The Ulugh Beg Observatory is an observatory in modern day Samarkand, Uzbekistan, which was built in the 1420s by the Timurid astronomer Ulugh Beg. This school of astronomy was constructed under the Timurid Empire, and was the last of its kind from the Islamic Medieval period. Islamic astronomers who worked at the observatory include Jamshid al-Kashi, Ali Qushji, and Ulugh Beg himself. The observatory was destroyed in 1449 and rediscovered in 1908.

Edward Stewart Kennedy was a historian of science specializing in medieval Islamic astronomical tables written in Persian and Arabic.

Muḥammad ibn Muḥammad ibn al-Ḥasan al-Ṭūsī, also known as Naṣīr al-Dīn al-Ṭūsī or simply as (al-)Tusi, was a Persian polymath, architect, philosopher, physician, scientist, and theologian. Nasir al-Din al-Tusi was a well published author, writing on subjects of math, engineering, prose, and mysticism. Additionally, al-Tusi made several scientific advancements. In astronomy, al-Tusi created very accurate tables of planetary motion, an updated planetary model, and critiques of Ptolemaic astronomy. He also made strides in logic, mathematics but especially trigonometry, biology, and chemistry. Nasir al-Din al-Tusi left behind a great legacy as well. Tusi is widely regarded as one of the greatest scientists of medieval Islam, since he is often considered the creator of trigonometry as a mathematical discipline in its own right. The Muslim scholar Ibn Khaldun (1332–1406) considered Tusi to be the greatest of the later Persian scholars. There is also reason to believe that he may have influenced Copernican heliocentrism.

Shams al-Din Muhammad b. Ahmad al-Khafri al-Kashi, known as Khafri, was an Iranian religious scholar and astronomer at the beginning of the Safavid dynasty. Before the arrival of Sheikh Baha'i in Iran, he was appointed as the major Shia jurist in the Safavid court. He was born in the city of Ḵafr, south east of Firuzābād in the region of Fārs. His exact date of birth is unknown but historical accounts estimate the date of his birth to be around the 1480s. He wrote on philosophy, religion, and astronomy, with the latter including a commentary on al-Tusi and critiques of al-Shirazi. Al-Khafri wrote works on theology and astronomy, indicating that Islamic scholars in his time and place saw no contradictions between Islam and science.

Nizam al-Din Hasan al-Nisaburi, whose full name was Nizam al-Din Hasan ibn Mohammad ibn Hossein Qumi Nishapuri was a Persian Sunni Islamic Shafi'i, Ash'ari scholar, mathematician, astronomer, jurist, Qur'an exegete, and poet.