Luciana Littizzetto is an Italian comedy actress, shock jock and humor writer.

Franco Basaglia was an Italian psychiatrist, neurologist, and professor, who proposed the dismantling of psychiatric hospitals, pioneer of the modern concept of mental health, Italian psychiatry reformer, figurehead and founder of Democratic Psychiatry, architect, and principal proponent of Law 180, which abolished mental hospitals in Italy. He is considered to be the most influential Italian psychiatrist of the 20th century.

Luigi Calabresi was an Italian Polizia di Stato officer in Milan. Responsible for investigating far-left political movements, Calabresi was assassinated in 1972 by members of Lotta Continua, who blamed him for the death of anarchist activist Giuseppe Pinelli in police custody in 1969. The deaths of Pinelli and Calabresi were significant events during the Years of Lead, a period of major political violence and unrest in Italy from the 1960s to the 1980s.

Fulvio Croce was an Italian lawyer. The president of the Turin Bar Association, he was killed by a terrorist group, the Red Brigades.

Basaglia Law or Law 180 is the Italian Mental Health Act of 1978 which signified a large reform of the psychiatric system in Italy, contained directives for the closing down of all psychiatric hospitals and led to their gradual replacement with a whole range of community-based services, including settings for acute in-patient care. The Basaglia Law is the basis of Italian mental health legislation. The principal proponent of Law 180 and its architect was Italian psychiatrist Franco Basaglia. Therefore, Law 180 is known as the “Basaglia Law” from the name of its promoter. The Parliament of Italy approved the Law 180 on 13 May 1978, and thereby initiated the gradual dismantling of psychiatric hospitals. Implementation of the psychiatric reform law was accomplished in 1998 which marked the very end of the state psychiatric hospital system in Italy. The Law has had worldwide impact as other counties took up widely the Italian model. It was Democratic Psychiatry which was essential in the birth of the reform law of 1978.

Democratic Psychiatry is an Italian real society, as well as a movement for liberation of the ill and weak from segregation in mental hospitals, by pushing for the Italian psychiatric reform. The movement was political in nature but not antipsychiatric in the sense in which this term is usually used in English. Democratic Psychiatry called for radical changes in the practice and theory of psychiatry and strongly attacked the way society managed mental illness. The movement was essential in the birth of the reform Basaglia Law of 1978.

Psychiatric reform in Italy is the reform of psychiatry which started in Italy after the passing of Basaglia Law in 1978 and terminated with the very end of the Italian state mental hospital system in 1998. Among European countries, Italy was the first to publicly declare its repugnance for a mental health care system which led to social exclusion and segregation. The psychiatric reform was also a consequence of a public debate sparked by Giorgio Coda's case and stories collected and analyzed in Alberto Papuzzi's book Portami su quello che canta.

Once Upon a Time the City of Fools is Italian television film of two episodes.

National Memorial Day of the Exiles and Foibe is an Italian commemoration of the victims of the Foibe and the Istrian–Dalmatian exodus, which led to the emigration of hundreds of thousands of local ethnic Italians from Yugoslavia after the end of the Second World War.

Giorgio Antonucci was an Italian physician, known for his questioning of the bases of psychiatry.

Stamina therapy was a controversial and unproven treatment marketed in Italy by convicted quack Davide Vannoni during 2007–2014. Mainly aimed at neurodegenerative diseases, the method relied on the conversion of mesenchymal stem cells into neurons. Its details were kept secret by its promoters and Vannoni has never published any details in a scientific journal. In the absence of scientific validation, claims of its therapeutic effectiveness are unproven.

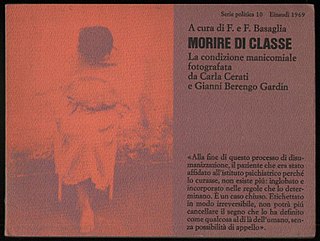

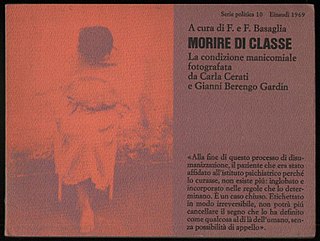

Morire di classe. La condizione manicomiale fotografata da Carla Cerati e Gianni Berengo Gardin, first published in 1969, is a polemical work about the conditions in Italian mental hospitals of the time, edited by Franco Basaglia and Franca Ongaro Basaglia and with black and white photographs by Carla Cerati and Gianni Berengo Gardin, an introduction by the Basaglias, and various other texts.

Sergio Cotta was an Italian philosopher, jurist and university professor. He was considered a specialist on the political thought of the Enlightenment. Cotta, along with André Masson and Robert Shackleton, was considered the most important interpreter of Montesquieu during the 20th century.

The term State-Mafia Pact describes an alleged series of negotiations between important Italian government officials and Cosa Nostra members that began after the period of the 1992 and 1993 terror attacks by the Sicilian Mafia with the aim to reach a deal to stop the attacks; according to other sources and hypotheses, it began even earlier. In summary, the supposed cornerstone of the deal was an end to "the Massacre Season" in return for a reduction in the detention measures provided for Italy's Article 41-bis prison regime. 41-bis was the law by which the Antimafia pool led by Giovanni Falcone had condemned hundreds of mafia members to the "hard prison regime". The negotiation hypothesis has been the subject of long investigations, both by the courts and in the media. In 2021, the Court of Appeal of Palermo acquitted a close associate of former prime minister Silvio Berlusconi, while upholding the sentences of the mafia bosses. This ruling was confirmed by the Italian Supreme Court of Cassation in 2023.

Claudia Letizia also known as Lady Letizia is an Italian actress, dancer, television and radio hostess and singer. She is known for having participated in the twelfth series of the reality show Grande Fratello, the Italian version of Big Brother.

The Mombello Psychiatric Hospital, also known as the Giuseppe Antonini of Limbiate Psychiatric Hospital, was the largest asylum in Italy, covering 40,000 m2 (430,000 sq ft) with multiple buildings located as to form a small village. It is located in the Italian commune of Limbiate, in the administrative district of Monza and Brianza, Lombard Province. Officially inaugurated in 1878, it was the last psychiatric hospital to be closed after the approval of the Legge Basaglia in 1978.

Ville Sbertoli was a lunatic asylum in Pistoia, Italy. The original structure was built in the 17th century. In 1868, it was bought by Agostino Sbertoli, who wanted to create a health facility for wealthy families. After serving as a political prison during World War II, it was transformed into a public psychiatric hospital in 1951. The complex was later abandoned.

Italy has the world's 48th largest exclusive economic zone (EEZ), with an area of 541,915 km2 (209,235 sq mi). It claims an EEZ of 200 nmi from its shores, which has long coastlines with the Tyrrhenian Sea to the west, the Ionian Sea to the south and the Adriatic Sea to the east. Its EEZ is limited by maritime boundaries with neighboring countries to the north-west, east and southeast.

A five-part abrogative referendum was held in Italy on 12 June 2022. Voters were asked to decide on the repeal of five articles or decrees relating to the functions of the Italian judicial system. Each of the five questions were submitted by nine Italian regions, all governed by the centre-right coalition.

Franco Rotelli was an Italian psychiatrist and essayist.