Related Research Articles

Macbeth was King of Scotland (Alba) from 1040 until his death. Alba covered only a portion of present-day Scotland.

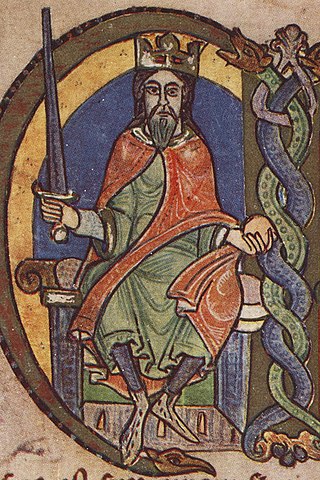

Malcolm III was King of Scotland from 1058 to 1093. He was later nicknamed "Canmore". Malcolm's long reign of 35 years preceded the beginning of the Scoto-Norman age. Henry I of England and Eustace III of Boulogne were his sons-in-law, making him the maternal grandfather of Empress Matilda, William Adelin and Matilda of Boulogne. All three of them were prominent in English politics during the 12th century.

Sir William Wallace was a Scottish knight who became one of the main leaders during the First War of Scottish Independence.

David I or Dauíd mac Maíl Choluim was a 12th-century ruler who was Prince of the Cumbrians from 1113 to 1124 and later King of Scotland from 1124 to 1153. The youngest son of Malcolm III and Margaret of Wessex, David spent most of his childhood in Scotland, but was exiled to England temporarily in 1093. Perhaps after 1100, he became a dependent at the court of King Henry I. There he was influenced by the Anglo-French culture of the court.

Malcolm IV, nicknamed Virgo, "the Maiden" was King of Scotland from 1153 until his death. He was the eldest son of Henry, Earl of Huntingdon and Northumbria and Ada de Warenne. The original Malcolm Canmore, a name now associated with his great-grandfather Malcolm III, succeeded his grandfather David I, and shared David's Anglo-Norman tastes.

Donald III, and nicknamed "Donald the Fair" or "Donald the White", was King of Scots from 1093 to 1094 and 1094–1097.

Andrew Moray, also known as Andrew de Moray, Andrew of Moray, or Andrew Murray, was an esquire, who became one of Scotland's war-leaders during the First Scottish War of Independence. Moray, son and heir to Sir Andrew Moray of Petty, an influential north Scotland baron, initially raised a small band of supporters at Avoch Castle in early summer 1297 to fight King Edward I of England, and soon had successfully regained control of the north for the absent Scots king, John Balliol. He subsequently merged his army with that of William Wallace, and jointly led the combined army to victory at the Battle of Stirling Bridge on 11 September 1297. Moray was mortally wounded in the fighting at Stirling, dying at an unknown date and place that year.

Clan Mackintosh is a Scottish clan from Inverness in the Scottish Highlands. The chiefs of the clan are the Mackintoshes of Mackintosh. Another branch of the clan, the Mackintoshes of Torcastle, are the chiefs of Clan Chattan, a historic confederation of clans.

The First War of Scottish Independence was the first of a series of wars between English and Scottish forces. It lasted from the English invasion of Scotland in 1296 until the de jure restoration of Scottish independence with the Treaty of Edinburgh–Northampton in 1328. De facto independence was established in 1314 at the Battle of Bannockburn. The wars were caused by the attempts of the English kings to establish their authority over Scotland while Scots fought to keep English rule and authority out of Scotland.

Clan MacDougall is a Highland Scottish clan, historically based in and around Argyll. The Lord Lyon King of Arms, the Scottish official with responsibility for regulating heraldry in Scotland, issuing new grants of coats of arms, and serving as the judge of the Court of the Lord Lyon, recognizes under Scottish law the Chief of Clan MacDougall. The MacDougall chiefs share a common ancestry with the chiefs of Clan Donald in descent from Somerled of the 12th century. In the 13th century the Clan MacDougall whose chiefs were the original Lords of Argyll and later Lords of Lorne was the most powerful clan in the Western Highlands. During the Wars of Scottish Independence the MacDougalls sided with the Clan Comyn whose chiefs rivaled Robert the Bruce for the Scottish Crown and this resulted in clan battles between the MacDougalls and Bruce. This marked the MacDougall's fall from power and led to the rise of their relatives, the Clan Donald, who had supported Bruce and also the rise to power of the Clan Campbell who were the habitual enemies of the MacDougalls and Clan Donald.

Moray was a province within the area of modern-day Scotland, that may at times up to the 12th century have operated as an independent kingdom or as a power base for competing claimants to the Kingdom of Alba. It covered a much larger territory than the modern council area of Moray, extending approximately from the River Spey in the east to the River Beauly in the north, and encompassing Badenoch, Lochaber and Glenelg in the south and west.

The Kingdom of Alba was the Kingdom of Scotland between the deaths of Donald II in 900 and of Alexander III in 1286. The latter's death led indirectly to an invasion of Scotland by Edward I of England in 1296 and the First War of Scottish Independence.

William fitz Duncan was a Scottish prince, the son of King Duncan II of Scotland by his wife Ethelreda of Dunbar. He was a territorial magnate in northern Scotland and northern England and a military leader.

The Meic Uilleim (MacWilliams) were the Gaelic descendants of William fitz Duncan, grandson of Máel Coluim mac Donnchada, king of Scots. They were excluded from the succession by the descendants of Máel Coluim's son David I during the 12th century and raised a number of rebellions to vindicate their claims to the Mormaerdom of Moray and perhaps to the rule of Scotland.

Harald Maddadsson was Earl of Orkney and Mormaer of Caithness from 1139 until 1206. He was the son of Matad, Mormaer of Atholl, and Margaret, daughter of Earl Haakon Paulsson of Orkney. Of mixed Norse and Gaelic blood, and a descendant of Scots kings, he was a significant figure in northern Scotland, and played a prominent part in Scottish politics of the twelfth century. The Orkneyinga Saga names him one of the three most powerful Earls of Orkney along with Sigurd Eysteinsson and Thorfinn Sigurdsson.

William Comyn was Lord of Badenoch and Earl of Buchan. He was one of the seven children of Richard Comyn, Justiciar of Lothian, and Hextilda of Tynedale. He was born in Scotland, in Altyre, Moray in 1163 and died in Buchan in 1233 where he is buried in Deer Abbey.

Ruaidhrí mac Raghnaill was a leading figure in the Kingdom of the Isles and a member of Clann Somhairle. He was a son of Raghnall mac Somhairle, and was the eponymous ancestor of Clann Ruaidhrí. Ruaidhrí may have become the principal member of Clann Somhairle following the annihilation of Aonghus mac Somhairle in 1210. At about this time, Ruaidhrí seems to have overseen a marital alliance with the reigning representative of the Crovan dynasty, Rǫgnvaldr Guðrøðarson, King of the Isles, and to have contributed to a reunification of the Kingdom of the Isles between Clann Somhairle and the Crovan dynasty.

Gofraid is an Irish masculine given name, arising in the Old Irish and Middle Irish/Middle Gaelic languages, as Gofhraidh, and later partially Anglicised as Goffraid.

Adam of Kilconquhar was a Scottish noble from the 13th century. Of Fife origin, he is notable for becoming the husband of the Countess of Carrick and participating in the Ninth Crusade under the command of Lord Edward, Duke of Gascony.

Clan Cumming, also known as Clan Comyn, is a Scottish clan from the central Highlands that played a major role in the history of 13th-century Scotland and in the Wars of Scottish Independence. The Clan Comyn was once the most powerful family in 13th-century Scotland, until they were defeated in civil war by their rival to the Scottish throne, Robert the Bruce.

References

- 1 2 3 "Bruce" . Retrieved 13 June 2007.[ permanent dead link ]

- ↑ "McDonald". Archived from the original on 29 September 2007. Retrieved 13 June 2007.

- ↑ MacDonald, p. 41.

- ↑ Duncan, pp. 110–112; MacDonald, pp. 41–42.

- ↑ Duncan, p. 112; MacDonald, pp.42–43.