Florence is the capital city of the Italian region of Tuscany. It is also the most populated city in Tuscany, with 360,930 inhabitants in 2023, and 984,991 in its metropolitan area.

The Republic of Florence, known officially as the Florentine Republic, was a medieval and early modern state that was centered on the Italian city of Florence in Tuscany, Italy. The republic originated in 1115, when the Florentine people rebelled against the Margraviate of Tuscany upon the death of Matilda of Tuscany, who controlled vast territories that included Florence. The Florentines formed a commune in her successors' place. The republic was ruled by a council known as the Signoria of Florence. The signoria was chosen by the gonfaloniere, who was elected every two months by Florentine guild members.

Piero di Cosimo de' Medici, known as Piero the Gouty, was the de facto ruler of Florence from 1464 to 1469, during the Italian Renaissance.

This article deals with the history of Tuscany.

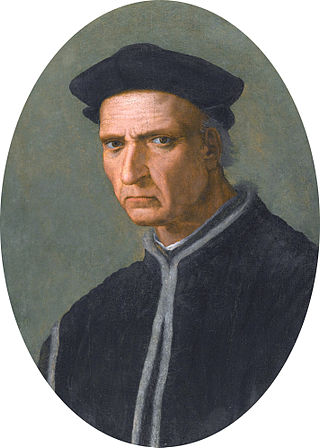

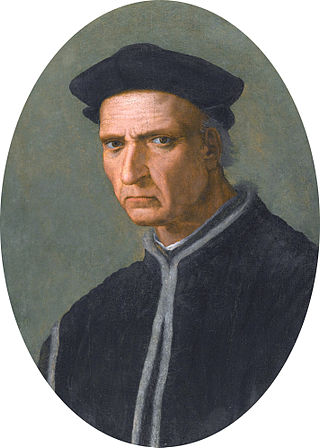

Francesco Guicciardini was an Italian historian and statesman. A friend and critic of Niccolò Machiavelli, he is considered one of the major political writers of the Italian Renaissance. In his masterpiece, The History of Italy, Guicciardini paved the way for a new style in historiography with his use of government sources to support arguments and the realistic analysis of the people and events of his time.

Piero di Tommaso Soderini, also known as Pier Soderini, was an Italian statesman of the Republic of Florence.

The House of Strozzi is the name of an ancient Florentine family, who like their great rivals the House of Medici, began in banking before moving into politics. Until its exile from Florence in 1434, the Strozzi family was by far the richest in the city, and was rivaled only by the Medici family, who ultimately took control of the government and ruined the Strozzi both financially and politically. This political and financial competition was the origin of the Strozzi-Medici rivalry. Later, while the Medici ruled Florence, the Strozzi family ruled Siena, which Florence attacked, causing great animosity between the two families. Soon afterward, the Strozzi married into the Medici family, essentially giving the Medici superiority.

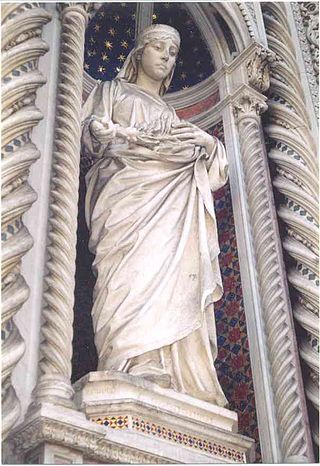

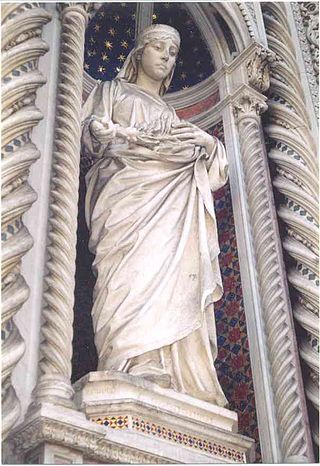

Hercules and Cacus is an Italian Renaissance sculpture in marble to the right of the entrance of the Palazzo Vecchio in the Piazza della Signoria, Florence, Italy.

Florence weathered the decline of the Western Roman Empire to emerge as a financial hub of Europe, home to several banks including that of the politically powerful Medici family. The city's wealth supported the development of art during the Italian Renaissance, and tourism attracted by its rich history continues today.

Giovanni Tornabuoni was an Italian merchant, banker and patron of the arts from Florence.

The palleschi, also known as bigi, were partisans of the Medici family in Florence. The name derived by the Medici coat-of-arms, bearing six 'balls' (palle).

The Gonfalonier was the holder of a highly prestigious communal office in medieval and Renaissance Italy, notably in Florence and the Papal States. The name derives from gonfalone, the term used for the banners of such communes.

This timeline lists important events relevant to the life of the Italian diplomat, writer and political philosopher Niccolò di Bernardo dei Machiavelli (1469–1527).

Paolo Antonio Soderini was a noble Florentine jurist active in the anti-Medicean Florentine republic, who spent some years resident at Rome.

The Pucci family has been a prominent noble family in Florence over the course of many centuries. A recent notable member of this family was Emilio Pucci, an Italian fashion designer who founded a clothing company after World War II.

Bernardo Rucellai, also known as Bernardo di Giovanni Rucellai or Latinised as Bernardus Oricellarius, was a member of the Florentine political and social elite. He was the son of Giovanni di Paolo Rucellai (1403–1481) and father of Giovanni di Bernardo Rucellai (1475–1525). He was married to Nannina de' Medici, the elder sister of Lorenzo de' Medici, and was thus uncle to Popes Leo X and Clement VII, who were cousins. Oligarch, banker, ambassador and man of letters, he is today remembered principally for the meetings of the members of the Accademia Platonica in the Orti Oricellari, the gardens of his house in Florence, the Palazzo Rucellai, where Niccolò Machiavelli gave readings of his Discorsi.

Giovanni Rucellai, known by his name with the patronymic Giovanni di Paolo Rucellai, was a member of a wealthy family of wool merchants in Renaissance Florence, in Tuscany, Italy. He held political posts under Cosimo and Lorenzo de' Medici, but is principally remembered for building Palazzo Rucellai and the Rucellai Sepulchre, for his patronage of the marble façade of the church of Santa Maria Novella, and as author of an important Zibaldone. He was the father of Bernardo Rucellai (1448–1514) and grandfather of Giovanni di Bernardo Rucellai (1475–1525).

Giovanni Rucellai, known as Giovanni di Bernardo Rucellai, was an Italian humanist, poet, dramatist and man of letters in Renaissance Florence, in Tuscany, Italy. A member of a wealthy family of wool merchants and one of the richest men in Florence, he was cousin to Pope Leo X and linked by marriage to the powerful Strozzi and de' Medici families. He was born in Florence, and died in Rome. He was the son of Bernardo Rucellai (1448–1514) and his wife Nannina de' Medici (1448–1493), and the grandson of Giovanni di Paolo Rucellai (1403–1481). He is now remembered mostly for his poem Le Api, one of the first poems composed in versi sciolti to achieve widespread acclaim.

Guglielmo di Antonio de' Pazzi, Lord of Civitella was an Italian nobleman, banker and politician from the Republic of Florence. He was also husband of Bianca de' Medici, sister of the Lord of Florence Lorenzo the Magnificent.