Porcelain is a ceramic material made by heating raw materials, generally including kaolinite, in a kiln to temperatures between 1,200 and 1,400 °C. The greater strength and translucence of porcelain, relative to other types of pottery, arise mainly from vitrification and the formation of the mineral mullite within the body at these high temperatures. End applications include tableware, decorative ware such as figurines, and products in technology and industry such as electrical insulators and laboratory ware.

Josiah Spode was an English potter and the founder of the English Spode pottery works which became famous for the high quality of its wares. He is often credited with the establishment of blue underglaze transfer printing in Staffordshire in 1781–84, and with the definition and introduction in c. 1789–91 of the improved formula for bone china which thereafter remained the standard for all English wares of this kind.

Spode is an English brand of pottery and homewares produced by the company of the same name, which is based in Stoke-on-Trent, England. Spode was founded by Josiah Spode (1733–1797) in 1770, and was responsible for perfecting two extremely important techniques that were crucial to the worldwide success of the English pottery industry in the century to follow.

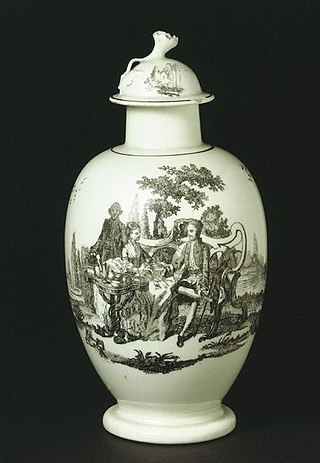

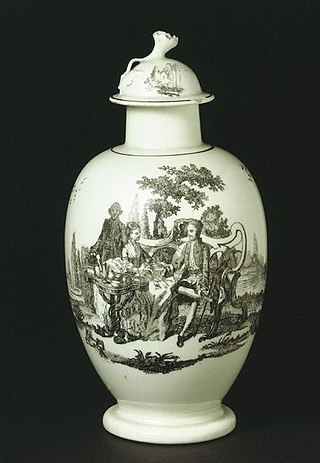

Transfer printing is a method of decorating pottery or other materials using an engraved copper or steel plate from which a monochrome print on paper is taken which is then transferred by pressing onto the ceramic piece. Pottery decorated using this technique is known as transferware or transfer ware.

Royal Worcester is a porcelain brand based in Worcester, England. It was established in 1751 and is believed to be the oldest or second oldest remaining English porcelain brand still in existence today, although this is disputed by Royal Crown Derby, which claims 1750 as its year of establishment. Part of the Portmeirion Group since 2009, Royal Worcester remains in the luxury tableware and giftware market, although production in Worcester itself has ended.

Wedgwood is an English fine china, porcelain and luxury accessories manufacturer that was founded on 1 May 1759 by the potter and entrepreneur Josiah Wedgwood and was first incorporated in 1895 as Josiah Wedgwood and Sons Ltd. It was rapidly successful and was soon one of the largest manufacturers of Staffordshire pottery, "a firm that has done more to spread the knowledge and enhance the reputation of British ceramic art than any other manufacturer", exporting across Europe as far as Russia, and to the Americas. It was especially successful at producing fine earthenware and stoneware that were accepted as equivalent in quality to porcelain but were considerably cheaper.

Thomas Minton (1765–1836) was an English potter. He founded Thomas Minton & Sons in Stoke-on-Trent, Staffordshire, which grew into a major ceramic manufacturing company with an international reputation.

The Willow pattern is a distinctive and elaborate chinoiserie pattern used on ceramic tableware. It became popular at the end of the 18th century in England when, in its standard form, it was developed by English ceramic artists combining and adapting motifs inspired by fashionable hand-painted blue-and-white wares imported from China. Its creation occurred at a time when mass-production of decorative tableware, at Stoke-on-Trent and elsewhere, was already making use of engraved and printed glaze transfers, rather than hand-painting, for the application of ornament to standardized vessels.

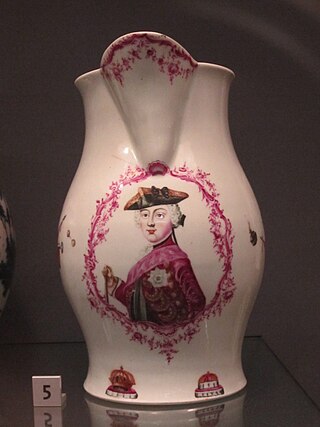

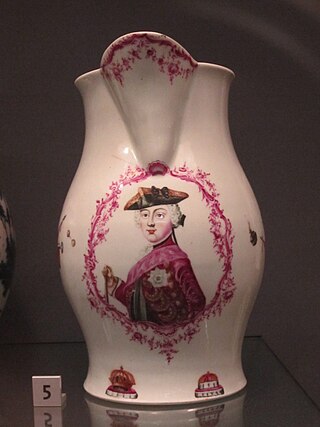

Liverpool porcelain is mostly of the soft-paste porcelain type and was produced between about 1754 and 1804 in various factories in Liverpool. Tin-glazed English delftware had been produced in Liverpool from at least 1710 at numerous potteries, but some then switched to making porcelain. A portion of the output was exported, mainly to North America and the Caribbean.

Mintons was a major company in Staffordshire pottery, "Europe's leading ceramic factory during the Victorian era", an independent business from 1793 to 1968. It was a leader in ceramic design, working in a number of different ceramic bodies, decorative techniques, and "a glorious pot-pourri of styles - Rococo shapes with Oriental motifs, Classical shapes with Medieval designs and Art Nouveau borders were among the many wonderful concoctions". As well as pottery vessels and sculptures, the firm was a leading manufacturer of tiles and other architectural ceramics, producing work for both the Houses of Parliament and United States Capitol.

Bristol porcelain covers porcelain made in Bristol, England by several companies in the 18th and 19th centuries. The plain term "Bristol porcelain" is most likely to refer to the factory moved from Plymouth in 1770, the second Bristol factory. The product of the earliest factory is usually called Lund's Bristol ware and was made from about 1750 until 1752, when the operation was merged with Worcester porcelain; this was soft-paste porcelain.

William Taylor Copeland, MP, Alderman was a British businessman and politician who served as Lord Mayor of London and a Member of Parliament.

William Duesbury (1725–1786) was an English enameller, in the sense of a painter of porcelain, who became an important porcelain entrepreneur, founder of the Royal Crown Derby and owner of porcelain factories at Bow, Chelsea, Derby and Longton Hall.

Davenport Pottery was an English earthenware and porcelain manufacturer based in Longport, Staffordshire. It was in business, owned and run by the Davenport family, between 1794 and 1887, making mostly tablewares in the main types of Staffordshire pottery.

Coalport, Shropshire, England was a centre of porcelain and pottery production between about 1795 and 1926, with the Coalport porcelain brand continuing to be used up to the present. The opening in 1792 of the Coalport Canal, which joins the River Severn at Coalport, had increased the attractiveness of the site, and from 1800 until a merger in 1814 there were two factories operating, one on each side of the canal, making rather similar wares which are now often difficult to tell apart.

The Ridgway family was one of the important dynasties manufacturing Staffordshire pottery, with a large number of family members and business names, over a period from the 1790s to the late 20th century. In their heyday in the mid-19th century there were several different potteries run by different branches of the family. Most of their wares were earthenware, but often of very high quality, but stoneware and bone china were also made. Many earlier pieces were unmarked and identifying them is difficult or impossible. Typically for Staffordshire, the various businesses, initially set up as partnerships, changed their official names rather frequently, and often used different trading names, so there are a variety of names that can be found.

The Lowestoft Porcelain Factory was a soft-paste porcelain factory on Crown Street in Lowestoft, Suffolk, England, which was active from 1757 to 1802. It mostly produced "useful wares" such as pots, teapots, and jugs, with shapes copied from silverwork or from Bow and Worcester porcelain. The factory, built on the site of an existing pottery or brick kiln, was later used as a brewery and malt kiln. Most of its remaining buildings were demolished in 1955.

Thomas Turner was an English potter. He was the lessee of the celebrated Salopian porcelain company, or Caughley manufactory, during the later decades of the 18th century. He is not to be confused with the potter John Turner (1737-1787) and his family, of Lane End, Staffordshire, who were active in the same period.

Leeds Pottery, also known as Hartley Greens & Co., is a pottery manufacturer founded around 1756 in Hunslet, just south of Leeds, England. It is best known for its creamware, which is often called Leedsware; it was the "most important rival" in this highly popular ware of Wedgwood, who had invented the improved version used from the 1760s on. Many pieces include openwork, made either by piercing solid parts, or "basketwork", weaving thin strips of clay together. Several other types of ware were produced, mostly earthenware but with some stoneware.

The Turner family of potters was active in Staffordshire, England 1756-1829. Their manufactures have been compared favourably with, and sometimes confused with, those of Josiah Wedgwood and Sons. Josiah Wedgwood was both a friend and a commercial rival of John Turner the elder, the first notable potter in the family.