Angola was first settled by San hunter-gatherer societies before the northern domains came under the rule of Bantu states such as Kongo and Ndongo. In the 15th century, Portuguese colonists began trading, and a settlement was established at Luanda during the 16th century. Portugal annexed territories in the region which were ruled as a colony from 1655, and Angola was incorporated as an overseas province of Portugal in 1951. After the Angolan War of Independence, which ended in 1974 with an army mutiny and leftist coup in Lisbon, Angola achieved independence in 1975 through the Alvor Agreement. After independence, Angola entered a long period of civil war that lasted until 2002.

The National Union for the Total Independence of Angola is the second-largest political party in Angola. Founded in 1966, UNITA fought alongside the People's Movement for the Liberation of Angola (MPLA) and the National Liberation Front of Angola (FNLA) in the Angolan War for Independence (1961–1975) and then against the MPLA in the ensuing civil war (1975–2002). The war was one of the most prominent Cold War proxy wars, with UNITA receiving military aid initially from the People's Republic of China from 1966 until October 1975 and later from the United States and apartheid South Africa while the MPLA received support from the Soviet Union and its allies, especially Cuba.

Jonas Malheiro Savimbi was an Angolan revolutionary, politician, and rebel military leader who founded and led the National Union for the Total Independence of Angola (UNITA). UNITA was one of several groups which waged a guerrilla war against Portuguese colonial rule from 1966 to 1974. Once independence was achieved, it then became an anti-communist group which confronted the ruling People's Movement for the Liberation of Angola (MPLA) during the Angolan Civil War. Savimbi had extensive contact with anti-communist activists in the United States, including Jack Abramoff and was one of the leading anti-communist voices in the world. Savimbi was killed in a clash with government troops in 2002.

The People's Movement for the Liberation of Angola, from 1977–1990 called the People's Movement for the Liberation of Angola – Labour Party, is an Angolan social democratic political party. The MPLA fought against the Portuguese Army in the Angolan War of Independence from 1961 to 1974, and defeated the National Union for the Total Independence of Angola (UNITA) and the National Liberation Front of Angola (FNLA) in the Angolan Civil War. The party has ruled Angola since the country's independence from Portugal in 1975, being the de facto government throughout the civil war and continuing to rule afterwards.

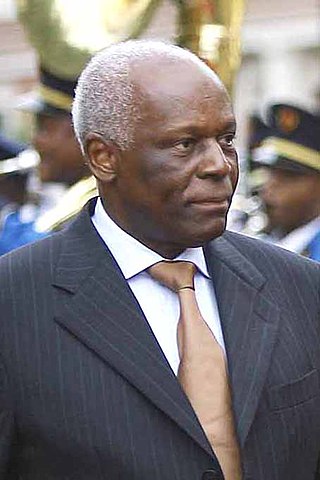

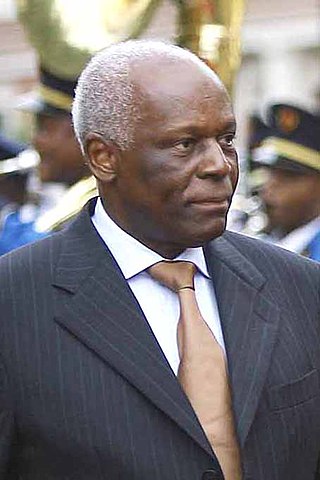

José Eduardo dos Santos was an Angolan politician and military officer who served as the second president of Angola from 1979 to 2017. As president, dos Santos was also the commander-in-chief of the Angolan Armed Forces (FAA) and president of the People's Movement for the Liberation of Angola (MPLA), the party that has ruled Angola since it won independence in 1975. By the time he stepped down in 2017, he was the second-longest-serving president in Africa, surpassed only by Teodoro Obiang Nguema Mbasogo of Equatorial Guinea.

Elections in Angola take place within the framework of a multi-party democracy. The National Assembly is directly elected by voters, while the leader of the party or coalition with the most seats in the National Assembly automatically becomes President.

The Angolan Civil War was a civil war in Angola, beginning in 1975 and continuing, with interludes, until 2002. The war began immediately after Angola became independent from Portugal in November 1975. It was a power struggle between two former anti-colonial guerrilla movements, the communist People's Movement for the Liberation of Angola (MPLA) and the anti-communist National Union for the Total Independence of Angola (UNITA).

The United Nations Angola Verification Mission II, established May 1991 and lasting until February 1995, was the second United Nations peacekeeping mission, of a total of four, deployed to Angola during the course of the Angolan Civil War, the longest war in modern African history. Specifically, the mission was established to oversee and maintain the multilateral ceasefire of 1990 and the subsequent Bicesse Accords in 1991, which instituted an electoral process for the first time including the two rival factions of the civil war, the People's Movement for the Liberation of Angola (MPLA), the de facto government of Angola, with control of Luanda and most of the country since independence in 1975, and the National Union for the Total Independence of Angola (UNITA).

The Bicesse Accords, also known as the Estoril Accords, laid out a transition to multi-party democracy in Angola under the supervision of the United Nations' UNAVEM II mission. President José Eduardo dos Santos of the MPLA and Jonas Savimbi of UNITA signed the accord in Lisbon, Portugal on May 31, 1991. UNITA rejected the official results of the 1992 presidential election as rigged and renewed their guerrilla war.

The National Assembly is the legislative branch of the government of Angola. Angola is a unicameral country so the National Assembly is the only legislative chamber at the national level. The People's Movement for the Liberation of Angola (MPLA) has held a majority in the Assembly since Angolan independence in 1975.

The Mitterrand–Pasqua affair, also known informally as Angolagate, was an international political scandal over the secret sale and shipment of arms from Central Europe to the government of Angola by the Government of France in the 1990s. The scandal has been tied to several prominent figures in French politics.

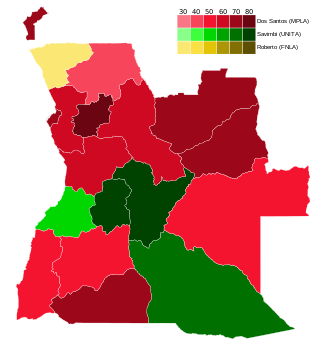

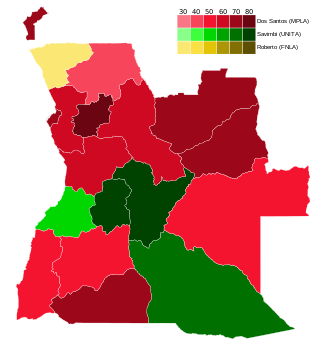

General elections were held in Angola on 29 and 30 September 1992 to elect a President and National Assembly, the first time free and multi-party elections had been held in the country. They followed the signing of the Bicesse Accord on 31 May 1991 in an attempt to end the 17-year-long civil war. Voter turnout was 91.3% for the parliamentary election and 91.2% for the presidential election.

The Alvor Agreement, signed on 15 January 1975 in Alvor, Portugal, granted Angola independence from Portugal on 11 November and formally ended the 13-year-long Angolan War of Independence.

The Lusaka Protocol, initialed in Lusaka, Zambia on 31 October 1994, attempted to end the Angolan Civil War by integrating and disarming UNITA and starting national reconciliation. Both sides signed a truce as part of the protocol on 15 November 1994, and the treaty was signed on 20 November 1994.

The Agreement among the People's Republic of Angola, the Republic of Cuba, and the Republic of South Africa granted independence to Namibia from South Africa and ended the direct involvement of foreign troops in the Angolan Civil War. The accords were signed on 22 December 1988 at the United Nations Headquarters in New York City by the Foreign Ministers of People's Republic of Angola, Republic of Cuba and Republic of South Africa.

Since its independence from Portugal in 1975, Angola has had three constitutions. The first came into force in 1975 as an "interim" measure; the second was approved in a 1992 referendum, and the third one was instituted in 2010.

In the 1980s in Angola, fighting spread outward from the southeast, where most of the fighting had taken place in the 1970s, as the African National Congress (ANC) and SWAPO increased their activity. The South African government responded by sending troops back into Angola, intervening in the war from 1981 to 1987, prompting the Soviet Union to deliver massive amounts of military aid from 1981 to 1986. The USSR gave the Angolan government over US$2 billion in aid in 1984. In 1981, newly elected United States President Ronald Reagan's U.S. assistant secretary of state for African affairs, Chester Crocker, developed a linkage policy, tying Namibian independence to Cuban withdrawal and peace in Angola.

Relations between Angola and South Africa in the post-apartheid era are quite strong as the ruling parties in both states, the African National Congress in South Africa and the MPLA in Angola, fought together during the Angolan Civil War and South African Border War. They fought against UNITA rebels, based in Angola, and the apartheid-era government in South Africa which supported them. Nelson Mandela mediated between the MPLA and UNITA during the final years of the Angolan Civil War. Although South Africa was preponderant in terms of relative capabilities during the late twentieth century, the recent growth of Angola has led to a more balanced relation.

In the 1990s in Angola, the last decade of the Angolan Civil War (1975–2002), the Angolan government transitioned from a nominally communist state to a nominally democratic one, a move made possible by political changes abroad and military victories at home. Namibia's declaration of independence, internationally recognized on April 1, eliminated the southwestern front of combat as South African forces withdrew to the east. The MPLA abolished the one-party system in June and rejected Marxist-Leninism at the MPLA's third Congress in December, formally changing the party's name from the MPLA-PT to the MPLA. The National Assembly passed law 12/91 in May 1991, coinciding with the withdrawal of the last Cuban troops, defining Angola as a "democratic state based on the rule of law" with a multi-party system.

The People's Republic of Angola was the self-declared socialist state which governed Angola from its independence in 1975 until 25 August 1992, during the Angolan Civil War.