Related Research Articles

YMCA, sometimes regionally called the Y, is a worldwide youth organization based in Geneva, Switzerland, with more than 64 million beneficiaries in 120 countries. It was founded on 6 June 1844 by George Williams in London, originally as the Young Men's Christian Association, and aims to put Christian values into practice by developing a healthy "body, mind, and spirit".

YWCA USA is a nonprofit organization dedicated to eliminating racism, empowering women, and promoting peace, justice, freedom, and dignity for all. It is one of the "oldest and largest multicultural organizations promoting solutions to enhance the lives of women, girls and families."

Madam C.J. Walker was an African American entrepreneur, philanthropist, and political and social activist. She is recorded as the first female self-made millionaire in America in the Guinness Book of World Records. Multiple sources mention that although other women might have been the first, their wealth is not as well-documented.

Dorothy Irene Height was an African American civil rights and women's rights activist. She focused on the issues of African American women, including unemployment, illiteracy, and voter awareness. Height is credited as the first leader in the civil rights movement to recognize inequality for women and African Americans as problems that should be considered as a whole. She was the president of the National Council of Negro Women for 40 years.

Reverdy Cassius Ransom was an American Christian socialist, civil rights activist, and leader in the African Methodist Episcopal Church. He was ordained and served as the 48th A.M.E. bishop.

Robert Charleton (1809–1872) was a Quaker, Recorded Minister and a prominent citizen of Bristol, England. He was a philanthropist and ran a pin-making factory which was noted for its good employment practices. He was an advocate of total abstinence and peaceful relations between nations.

Nannie Helen Burroughs was an educator, orator, religious leader, civil rights activist, feminist, and businesswoman in the United States. Her speech "How the Sisters Are Hindered from Helping," at the 1900 National Baptist Convention in Virginia, instantly won her fame and recognition. In 1909, she founded the National Training School for Women and Girls in Washington, DC. Burroughs' objective was at the point of intersection between race and gender.

The Young Women's Christian Association (YWCA) is a nonprofit organization with a focus on empowerment, leadership, and rights of women, young women, and girls in more than 100 countries.

The Boston Young Women's Christian Association (YWCA) (est.1866) was founded in Boston, Massachusetts, "to aid the young working-women of Boston, without regard to their religious belief." It was incorporated in 1867 by Pauline A. Durant, Ann Maria Sawyer, Hannah A. Bowen, and Clara L. Wells. It is the United States' oldest YWCA. With a mission to eliminate racism, empower women and promote peace, justice, freedom and dignity for all, the organization has been providing services to Boston residents and visitors for 150 years.

Jane Edna Hunter, an African-American social worker, was born near Pendleton, South Carolina. In 1911 she established the Working Girls Association in Cleveland, Ohio, which later became the Phillis Wheatley Association of Cleveland.

The White Rose Mission was created on February 11, 1897 as a "Christian, nonsectarian Home for Colored Girls and Women" by African American civic leaders, Victoria Earle Matthews (1861–1907) and Maritcha Remond Lyons (1848–1929). The settlement house, located on Manhattan's Upper West side in the neighborhood known then as San Juan Hill, was founded to offer refuge, shelter and food for newly arrived African American /Colored women from the southern United States and the West Indies. Aware of the perilous conditions for young African American women seeking work in New York City, Matthews and Lyons and other volunteers working with The White Rose Mission met incoming vessels. At Manhattan’s piers, docks and railway stations, volunteers offered assistance to female travelers who often fell prey to unscrupulous employment agents and con artists. As traveler’s assistance services were generally not available to African American women, the White Rose Mission, under the direction of Victoria Earle Matthews, was founded to address the specific problems facing African American female migrants.

Ruth Logan Roberts was a suffragist, activist, YWCA leader, and host of a salon in Harlem, New York City.

Cecelia Cabaniss Saunders sometimes written as Cecilia Cabaniss Saunders, was an African-American civil rights leader, and executive director of the Harlem, New York YWCA. She is best known for working against racial discrimination in wartime employment during World War II, for broader work training and opportunities for African-American women, and against police violence in Harlem.

Eva del Vakia Bowles was an American teacher and a Young Women's Christian Association organizer in New York City. When she began working at the New York City segregated YWCA in Harlem, she became the first black woman to be a general secretary of the organization. For eighteen years she organized black branches of the YWCA and expanded their services to community members. She received recognition from former president Theodore Roosevelt for her work during World War I on behalf of the segregated Y.

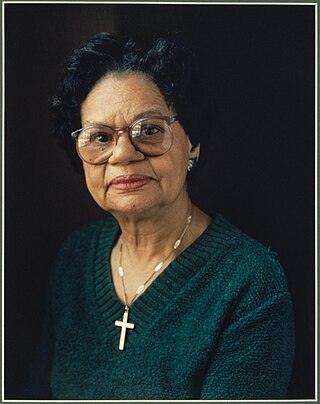

Olivia Pearl Stokes was a religious educator, ordained Baptist minister, author, administrator, and civil rights activist. As the first African American woman to receive a doctorate in religious education, Stokes was a pioneer in her field dedicated to empowering disenfranchised and underrepresented groups. A majority of her work reflects her primary role as a religious educator, her commitment to develop leadership training, and her efforts to eliminate negative stereotypes of women and African Americans. She was also an avid student of African cultures, and developed programs to promote understanding of African civilizations.

Judith Weisenfeld is an American scholar of religion. She is Agate Brown and George L. Collord Professor of Religion at Princeton University, where she is also the Chair of the Department of Religion. Her research primarily focuses on African-American religion in the first half of the 20th century. In 2019, Weisenfeld was elected to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences.

Etnah Rochon Boutte was an American educator, pharmacist, and clubwoman. She taught French at Fisk University and in New York City. She was executive secretary of the Circle for Negro War Relief during World War I.

Emma S. Connor Ransom was an American educator and clubwoman, active in the African Methodist Episcopal Church (AME) and the YWCA.

Frances Reynolds Keyser was an American suffragist, clubwoman, and educator. She succeeded Victoria Earle Matthews as superintendent of the White Rose Mission in New York City, and was academic dean of the Daytona Normal and Industrial Institute alongside school founder Mary McLeod Bethune.

YWCA of Greater Portland is a charitable organization with a mission to eliminate racism, empower women, and promote peace, justice, freedom, and dignity for all. The organization serves Multnomah County in four major areas of programming including youth services, domestic violence services, senior services, and social change.

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Weisenfeld, Judith (1994). "The Harlem YWCA and the Secular City, 1904-1945". Journal of Women's History. 6 (3): 62–78. doi:10.1353/jowh.2010.0312.

- 1 2 Judith Weisenfeld, African American Women and Christian Activism: New York's Black YWCA, 1905-1945 (Harvard University Press 1997): 115. ISBN 9780674007789

- 1 2 Williams, Hettie V. (2017). Bury My Heart in a Free Land: Black Women Intellectuals in Modern U.S. History. p. 354. ISBN 978-1440835483.

- ↑ Stout, Harry S.; Hart, D. G. (1998). New Directions in American Religious History. Oxford University Press. p. 516. ISBN 978-0195112139.