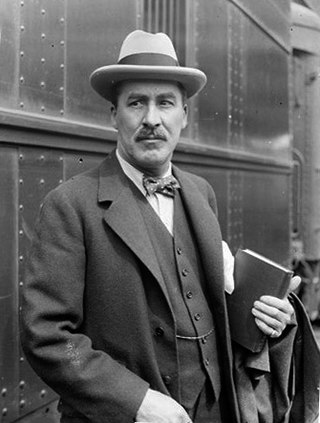

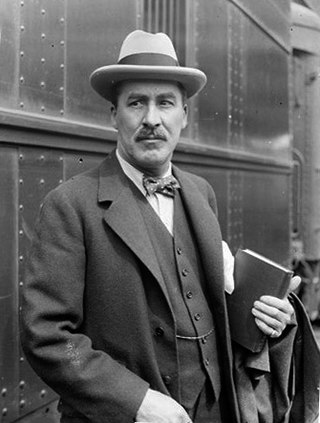

Howard Carter was a British archaeologist and Egyptologist who discovered the intact tomb of the 18th Dynasty Pharaoh Tutankhamun in November 1922, the best-preserved pharaonic tomb ever found in the Valley of the Kings.

Tutankhamun or Tutankhamen, was an ancient Egyptian pharaoh who ruled c. 1332 – 1323 BC during the late Eighteenth Dynasty of ancient Egypt. Born Tutankhaten, he was likely a son of Akhenaten, thought to be the KV55 mummy. His mother was identified through DNA testing as The Younger Lady buried in KV35; she was a full sister of her husband.

Nefertiti was a queen of the 18th Dynasty of Ancient Egypt, the great royal wife of Pharaoh Akhenaten. Nefertiti and her husband were known for their radical overhaul of state religious policy, in which they promoted the earliest known form of monotheism, Atenism, centered on the sun disc and its direct connection to the royal household. With her husband, she reigned at what was arguably the wealthiest period of ancient Egyptian history. After her husband's death, some scholars believe that Nefertiti ruled briefly as the female pharaoh known by the throne name, Neferneferuaten and before the ascension of Tutankhamun, although this identification is a matter of ongoing debate. If Nefertiti did rule as pharaoh, her reign was marked by the fall of Amarna and relocation of the capital back to the traditional city of Thebes.

Tiye was the Great Royal Wife of the Egyptian pharaoh Amenhotep III, mother of pharaoh Akhenaten and grandmother of pharaoh Tutankhamun; her parents were Yuya and Thuya. In 2010, DNA analysis confirmed her as the mummy known as "The Elder Lady" found in the tomb of Amenhotep II (KV35) in 1898.

Zahi Abass Hawass is an Egyptian archaeologist, Egyptologist, and former Minister of Tourism and Antiquities, serving twice. He has worked at archaeological sites in the Nile Delta, the Western Desert and the Upper Nile Valley.

Smenkhkare was an ancient Egyptian pharaoh of unknown background who lived and ruled during the Amarna Period of the 18th Dynasty. Smenkhkare was husband to Meritaten, the daughter of his likely co-regent, Akhenaten. Since the Amarna period was subject to a large-scale condemnation of memory by later pharaohs, very little can be said of Smenkhkare with certainty, and he has hence been subject to immense speculation.

The tomb of Tutankhamun, a pharaoh of the Eighteenth Dynasty of ancient Egypt, is located in the Valley of the Kings. The tomb, also known by its tomb number KV62, consists of four chambers and an entrance staircase and corridor. It is smaller and less extensively decorated than other Egyptian royal tombs of its time, and it probably originated as a tomb for a non-royal individual that was adapted for Tutankhamun's use after his premature death. Like other pharaohs, Tutankhamun was buried with a wide variety of funerary objects and personal possessions, such as coffins, furniture, clothing and jewelry, though in the unusually limited space these goods had to be densely packed. Robbers entered the tomb twice in the years immediately following the burial, but Tutankhamun's mummy and most of the burial goods remained intact. The tomb's low position, dug into the floor of the valley, allowed its entrance to be hidden by debris deposited by flooding and tomb construction. Thus, unlike other tombs in the valley, it was not stripped of its valuables during the Third Intermediate Period.

Kiya was one of the wives of the Egyptian Pharaoh Akhenaten. Little is known about her, and her actions and roles are poorly documented in the historical record, in contrast to those of Akhenaten's 'Great royal wife', Nefertiti. Her unusual name suggests that she may originally have been a Mitanni princess. Surviving evidence demonstrates that Kiya was an important figure at Akhenaten's court during the middle years of his reign, when she had a daughter with him. She disappears from history a few years before her royal husband's death. In previous years, she was thought to be mother of Tutankhamun, but recent DNA evidence suggests this is unlikely.

Ay was the penultimate pharaoh of ancient Egypt's 18th Dynasty. He held the throne of Egypt for a brief four-year period in the late 14th century BC. Prior to his rule, he was a close advisor to two, and perhaps three, other pharaohs of the dynasty. It is speculated that he was the power behind the throne during child ruler Tutankhamun's reign. His prenomenKheperkheperure means "Everlasting are the Manifestations of Ra", while his nomenAy it-netjer reads as "Ay, Father of the God". Records and monuments that can be clearly attributed to Ay are rare, both because his reign was short and because his successor, Horemheb, instigated a campaign of damnatio memoriae against him and the other pharaohs associated with the unpopular Amarna Period.

The area of the Valley of the Kings, in Luxor, Egypt, has been a major area of modern Egyptological exploration for the last two centuries. Before this, the area was a site for tourism in antiquity. This area illustrates the changes in the study of ancient Egypt, beginning as antiquity hunting and ending with the scientific excavation of the whole Theban Necropolis. Despite the exploration and investigation noted below, only eleven of the tombs have actually been completely recorded.

The Valley of the Kings, also known as the Valley of the Gates of the Kings, is an area in Egypt where, for a period of nearly 500 years from the Eighteenth Dynasty to the Twentieth Dynasty, rock-cut tombs were excavated for pharaohs and powerful nobles under the New Kingdom of ancient Egypt.

Harry Burton was an English archaeological photographer, best known for his photographs of excavations in Egypt's Valley of the Kings. Today, he is sometimes referred to as an Egyptologist, since he worked for the Egyptian Expedition of the Metropolitan Museum of Art for around 25 years, from 1915 until his death. His most famous photographs are the estimated 3,400 or more images that he took documenting Howard Carter's excavation of Tutankhamun's tomb from 1922 to 1932.

Exhibitions of artifacts from the tomb of Tutankhamun have been held at museums in several countries, notably the United Kingdom, Soviet Union, United States, Canada, Japan, and France.

The curse of the pharaohs or the mummy's curse is a curse alleged to be cast upon anyone who disturbs the mummy of an ancient Egyptian, especially a pharaoh. This curse, which does not differentiate between thieves and archaeologists, is claimed to cause bad luck, illness, or death. Since the mid-20th century, many authors and documentaries have argued that the curse is 'real' in the sense of having scientifically explicable causes such as bacteria, fungi or radiation. However, the modern origins of Egyptian mummy curse tales, their development primarily in European cultures, the shift from magic to science to explain curses, and their changing uses—from condemning disturbance of the dead to entertaining horror film audiences—suggest that Egyptian curses are primarily a cultural, not scientific, phenomenon.

Tutankhamun's mummy was discovered by English Egyptologist Howard Carter and his team on 28 October 1925 in tomb KV62 in the Valley of the Kings. Tutankhamun was the 13th pharaoh of the 18th Dynasty of the New Kingdom of Egypt, making his mummy over 3,300 years old. Tutankhamun's mummy is notable for being the only royal mummy to have been found entirely undisturbed.

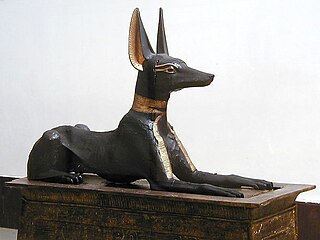

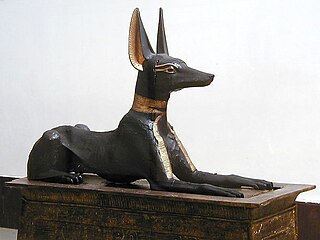

The Anubis Shrine was part of the burial equipment of the 18th Dynasty pharaoh Tutankhamun, whose tomb in the Valley of the Kings was discovered almost intact in 1922 by Egyptologists led by Howard Carter. Today the object, with the find number 261, is on display at the Egyptian Museum in Cairo, with the inventory number JE 61444.

The Lotus chalice or Alabaster chalice, called the Wishing Cup by Howard Carter, derives from the tomb of the Ancient Egyptian pharaoh Tutankhamun of the 18th Dynasty. The object received the find number 014 and was on display in the Egyptian Museum in Cairo, with the inventory numbers JE 67465 and GEM 36. It has been moved to the as yet unopened Grand Egyptian Museum.

Tut is a Canadian-American miniseries that premiered on American cable network Spike on July 19, 2015. The three-part miniseries is based on the life of Egyptian pharaoh Tutankhamun.

The mask of Tutankhamun is a gold funerary mask that belonged to Tutankhamun, who reigned over the New Kingdom of Egypt from 1332 BC to 1323 BC, during the Eighteenth Dynasty. After being buried with Tutankhamun's mummy for over 3,000 years, it was found amidst the discovery of Tutankhamun's tomb by the British archaeologist Howard Carter at the Valley of the Kings in 1925. Since then, it has been on display at the Egyptian Museum in the city of Cairo. In addition to being one of the best-known works of art in the world, it is a prominent symbol of ancient Egypt.

Mummies 317a and 317b were the infant daughters of Tutankhamun, a pharaoh of the Eighteenth Dynasty of Egypt. Their mother, who has been tentatively identified through DNA testing as the mummy KV21A, is presumed to be Ankhesenamun, his only known wife. 317a was born prematurely at 5–6 months' gestation, and 317b was born at or near full term. They are assumed to have been stillborn or died shortly after birth.