The Hellenistic Arsenal, located on the Kolonos Agoraios in Athens to the west of the Agora and north of the Temple of Hephaestus, is It was one of the largest structures in Athens during the Hellenistic period. [1]

The Hellenistic Arsenal, located on the Kolonos Agoraios in Athens to the west of the Agora and north of the Temple of Hephaestus, is It was one of the largest structures in Athens during the Hellenistic period. [1]

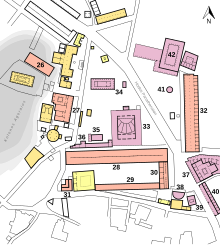

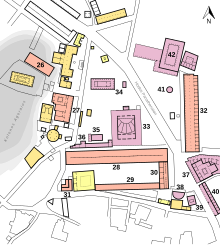

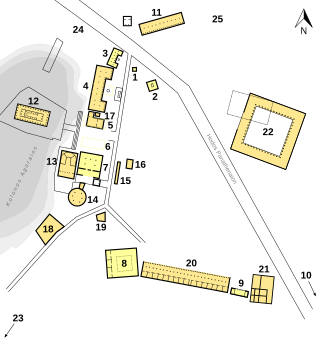

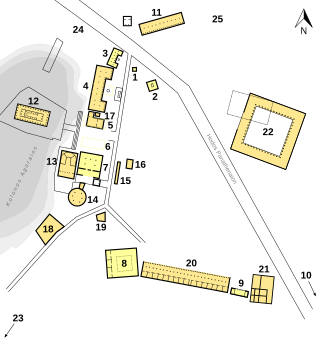

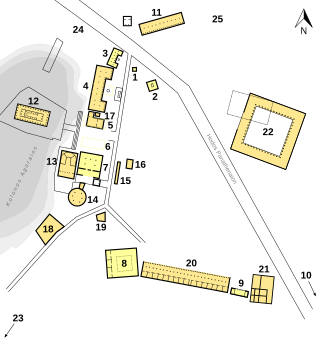

The arsenal was a long, rectangular building, with a northwest–southeast orientation, located north of the Temple of Hephaestus on the Kolonos Agoraios (the hill to the west of the Athenian Agora). [1] The entrance was at the northwestern end. [2] The building was aligned with and accessed from a paved road that ran from the Pnyx to the north slope of the Kolonos Agoraios, where it was linked to the Sacred Way by a staircase. [3] The arsenal was not accessible from the Agora. [2]

The arsenal was 44.40 metres long and 17.62 metres wide. Its walls were 0.98 metres thick. [4] Inside, the structure was divided into three aisles by two rows of eight columns with bases measuring 1.70 x 1.70 metres. [5] each column is 4.82 metres from the next one. [6] The central aisle is 5.10 metres wide; the side aisles are 4.60 metres wide. [7] These columns were aligned with eight piers or engaged columns on the inside of each of the long walls. [6] A wall 0.5 metres south of the arsenal runs parallel with its south wall and separates it from the precinct of the Temple of Hephaestus, probably to prevent water flowing down from the precinct into the arsenal. This wall impinges on the northeast corner of the Classical wall of the precinct of the Temple of Hephaestus about 15 metres from the eastern end of the arsenal. [8]

The trenches cut into the bedrock for the foundations of the long walls are preserved for large stretches. Blocks from the foundation remain in situ at the northern and southern corners. The rest of the masonry, including the whole superstructure, has been spoliated. [1] The surviving foundation blocks are made of high-quality, reddish, hard conglomerate. [6] The walls probably consisted of a row of poros orthostates and then mudbricks above that. [4] If there were windows, they were small and high up. [2] The columns and pilasters supported timber joists of a gable roof. [4]

There were two cisterns linked to the arsenal. The "Egyptian cistern", named for the Egyptian faience found inside it, [9] was located at the southwest corner of the arsenal. The other cistern, called the "cistern of Group C" was in the middle of its northern side. Both of these cisterns consisted of two chambers - one located inside the building and the other outside - linked together by winding passageway. [10] Rainwater would have flowed into them as it washed off the arsenal's roof. [11]

The date of construction is indicated by a third cistern, called "the Cave", which had served a house in the area, but was closed when the arsenal was built. [10] Pottery and coinage found in the cistern suggest that this closure occurred in the 260s. [12] Pottery deposits in the foundations tend to a similar period. [12] Pounder therefore places construction in the 270s-260s BC, a period of tension between Athens and Antigonid Macedonia, which culminated in the Chremonidean War. [13] [14]

The building has been identified as an arsenal because it resembles the mid-fourth century Naval Arsenal in the Piraeus. [15] Close similarities in measurements suggest that the Hellenistic Arsenal was directly modelled on the Naval Arsenal. [4] The location next to the Temple of Hephaestus, the armourer of the gods, might also have been appropriate for an arsenal. [13] The location was also appropriate because there were metalworking operations in the vicinity. [13] The Hipparcheion, the headquarters for Athens' cavalry also seems to have been located in the general area. [16] The location would also have been convenient for supplying Athenian troops, when they marshalled in the Agora. [17] The water from the cisterns may have been used to clean the weapons and armour stored in the arsenal. [11] Before the construction of the Hellenistic Arsenal, some weapons and armour were kept on the Acropolis in the Chalkotheke, but the majority must have been stored somewhere in the lower city. It is unclear where. [18]

Pounder suggests that the arsenal served as a headquarters for the treasurer of the military fund (Ancient Greek : ταμίας τῶν στρατιωτικῶν, romanized: tamias ton stratiotikon), because this officer suddenly reappears in the epigraphic record in an inventory list of the Asclepieion from 273/2 BC (IG II2 674), [19] and proposes that the structure was built around the year of this reappearance. [20]

G. Roger Edwards suggests that the arsenal was also used to store olive oil for victors in athletic games, because many fragments from the Panathenaic amphorae, which were awarded to victors in the Panathenaic Games, have been found in the area. [21] This fits with Pounder's theory, since the treasurer of the military fund was responsible for distributing the oil to the organisers of the Panathenaic Games in the Hellenistic period. [22]

The date when the arsenal went out of use is indicated by the deposits in the two cisterns linked with the structure. The Group C cistern went out of use after 200 BC, probably around 175-150 BC. [23] while the Egyptian cistern contains a main deposit dating between ca. 150 and 110 BC, [24] and a supplemental deposit early in the first century BC, which includes sculptural fragments broken off from the Temple of Hephaestus. The main deposit seems to indicate that the cistern had gone out of use; it is unclear why. [24] The final deposit most likely means that the building was destroyed during the Sullan Sack of Athens in 86 BC. [25] [26] Destruction fill over the southern foundations consists of mortar from the walls, tiles from the roof, and late Hellenistic pottery. [27] There is no evidence for burning; Pounder suggests that the building was disassembled so that the roof timbers could be used for siege equipment as Sulla attacked Athenian defenders still holed up on the Acropolis. [28]

The area was heavily occupied after the arsenal's destruction. Over the following centuries, the structure was slowly spoliated for other buildings, [28] such as the Temple of Ares in the Agora. [29] [30] Remains of later houses, wells, and cisterns from the Roman, Byzantine, and Ottoman periods overlie the remains of the arsenal. [31]

The Hellenistic arsenal was excavated by the American School of Classical Studies at Athens, as part of their Agora excavations in 1936 and 1937. The work was supervised by Dorothy Burr Thompson in the first year and Homer A. Thompson in the second. [31]

Alcamenes was an ancient Greek sculptor of Lemnos and Athens, who flourished in the 2nd half of the 5th century BC. He was a younger contemporary of Phidias and noted for the delicacy and finish of his works, among which a Hephaestus and an Aphrodite of the Gardens were conspicuous.

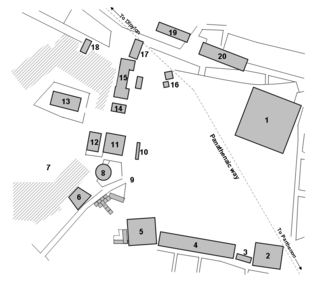

Eleusinion, also called the City Eleusinion was a sanctuary on the lower part of the north slope of the Acropolis in Athens, Greece, dedicated to Demeter and Kore (Persephone). It was the central hub of Eleusinian Mysteries within Athens and the starting point for the annual procession to Eleusis, in the northwest of Attica. Religious activity is attested in the area from the 7th century BC and construction took place throughout late Archaic, Classical, Hellenistic, and Roman periods. The sanctuary was enclosed within the new city walls built after the Herulian sack of Athens in AD 267 and it remained in use until the late fourth century AD.

The agora was a central public space in ancient Greek city-states. It is the best representation of a city-state's response to accommodate the social and political order of the polis. The literal meaning of the word "agora" is "gathering place" or "assembly". The agora was the center of the athletic, artistic, business, social, spiritual, and political life in the city. The Ancient Agora of Athens is the best-known example.

The Panathenaea was a multi-day ancient Greek festival held annually in Athens that would always conclude on 28 Hekatombaion, the first month of the Attic calendar. The main purpose of the festival was for Athenians and non-Athenians to celebrate the goddess Athena. Every four years, the festival was celebrated in a larger manner over a longer time period with increased festivities and was known as the Great (or Greater) Panathenaea. In the years that the festival occurred that were not considered the Great Panathenaea, the festival was known as the Lesser Panathenaea. The festival consisted of various competitions and ceremonies, culminating with a religious procession that ended in the Acropolis of Athens.

The Temple of Hephaestus or Hephaisteion, is a well-preserved Greek temple dedicated to Hephaestus; it remains standing largely intact today. It is a Doric peripteral temple, and is located at the north-west side of the Agora of Athens, on top of the Agoraios Kolonos hill. From the 7th century until 1834, it served as the Greek Orthodox church of Saint George Akamates. The building's condition has been maintained due to its history of varied use.

The ancient Agora of Athens is the best-known example of an ancient Greek agora, located to the northwest of the Acropolis and bounded on the south by the hill of the Areopagus and on the west by the hill known as the Agoraios Kolonos, also called Market Hill. The Agora's initial use was for a commercial, assembly, or residential gathering place.

The Stoa Poikile or Painted Portico was a Doric stoa erected around 460 BC on the north side of the Ancient Agora of Athens. It was one of the most famous sites in ancient Athens, owing its fame to the paintings and war-booty displayed within it and to its association with ancient Greek philosophy, especially Stoicism.

The Panhellenion or Panhellenium was a league of Greek city-states established in the year 131–132 AD by the Roman Emperor Hadrian while he was touring the Roman provinces of Greece. The League was established following a ceremony at the Temple of Olympian Zeus in Athens, the capital city of the Panhellenion. Evidence suggests that the Panhellenion continued to survive until the 250s AD.

Stoa Basileios, meaning Royal Stoa, was a Doric stoa in the northwestern corner of the Athenian Agora, which was built in the 6th century BC, substantially altered in the 5th century BC, and then carefully preserved until the mid-second century AD. It is among the smallest known Greek stoas, but had great symbolic significance as the seat of the Athenian King Archon, repository of Athens' laws, and site of "the stone" on which incoming magistrates swore their oath of office.

The South Stoa I of Athens was a two-aisled stoa located on the south side of the Agora, in Athens, Greece, between the Aiakeion and the Southeast Fountain House. It probably served as the headquarters and dining rooms for various boards of Athenian officials. It was built at the end of the 5th century BC and remained in use until the mid-second century BC, when it was replaced by South Stoa II.

The Ares Borghese is a Roman marble statue of the imperial era. It is 2.11 metres high. Though the statue is referred to as Ares, this identification is not entirely certain. This statue possibly preserves some features of an original work in bronze, now lost, of the 5th century BC.

The Temple of Ares was a Doric hexastyle peripteral temple dedicated to Ares, located in the northern part of the Ancient Agora of Athens. Fragments from the temple found throughout the Agora enable a full, if tentative, reconstruction of the temple's appearance and sculptural programme. The temple had a large altar to the east and was surrounded by statues. A terrace to the north looked down on the Panathenaic Way. The northwest corner of the temple overlays one of the best-preserved Mycenaean tombs in the Agora, which was in use from ca. 1450-1000 BC.

The Sanctuary of Aphrodite Urania was located north-west of the Ancient Agora of Athens and dedicated to the goddess Aphrodite under her epithet Urania. It has been identified with a sanctuary found in this area in the 1980s. This sanctuary initially consisted of a marble altar that was built around 500 BC and was gradually buried as the ground level rose. Another structure, perhaps a fountainhouse, was built to the west ca. 100 BC. In the early 1st century AD, an Ionic tetrastyle prostyle temple closely modelled on the Erechtheion's north porch, that was built to the north of the altar.

The Temple of Apollo Patroos is a small ruined temple on the west side of the Ancient Agora of Athens. The original temple was an apsidal structure, built in the mid-sixth century BC and destroyed in 480/79 BC. The area probably remained sacred to Apollo. A new hexastyle ionic temple was built ca. 306-300 BC, which has an unusual L-shaped floor plan. Some fragments from the sculptural decoration of this structure survive. The colossal cult statue, by Euphranor, has also been recovered.

The Sanctuary of Demeter and Kore on Acrocorinth was a temple in Ancient Corinth, dedicated to the goddesses Demeter and Kore (Persephone).

Olga Palagia is Professor of Classical Archaeology at the National and Kapodistrian University of Athens and is a leading expert on ancient Greek sculpture. She is known in particular for her work on sculpture in ancient Athens and has edited a number of key handbooks on Greek sculpture.

The Southwest Temple is the modern name for a tetrastyle prostyle Doric temple located in the southwest part of the Ancient Agora of Athens. Fragments from the temple found throughout the Agora enable a full, if tentative, reconstruction of the temple's appearance. These fragments originally belonged to several Hellenistic structures and a fifth-century BC stoa at Thorikos in southeastern Attica, but they were spoliated to build the temple in the Agora in the age of Augustus. It is unknown which god or hero the temple was dedicated to. It was spoliated to build the post-Herulian fortification wall after the Herulian sack of Athens in 267 AD.

The Southeast Temple is the modern name for an Ionic octastyle prostyle temple located in the southeast corner of the Ancient Agora of Athens. Architectural fragments from the temple enable a full, if tentative, reconstruction of its appearance.These fragments originally belonged to the Temple of Athena at Sounion at the southern tip of Attica, but they were spoliated to build the temple in the Agora in the first half of the second century AD. It was thus the last of several "itinerant temples," relocated from the Attic countryside to the Athenian Agora in the Imperial period. It is unknown which god or hero it was dedicated to. It was heavily damaged during the Herulian Sack of Athens in 267 AD and then spoliated to build the post-Herulian fortification wall.

South Stoa II was a stoa on the south side of the Agora in ancient Athens. It formed the south side of an enclosed complex called the South Square, which was built in the mid-second century BC and may have been intended for use as lawcourts.

The East Building was a rectangular structure at the south end of the Agora in ancient Athens. It was built in the mid-second century BC as the east side and main entrance to an enclosed complex called the South Square, which may have served as a commercial area or as lawcourts. The structure was damaged in the Sullan Sack of 86 BC and used for industrial purposes until the early second century AD when it was rebuilt. It was demolished after the Herulian Sack of 267 AD and used as building material for the Post-Herulian Wall.