Related Research Articles

Kabbalah or Qabalah is an esoteric method, discipline and school of thought in Jewish mysticism. A traditional Kabbalist is called a Mekubbal. The definition of Kabbalah varies according to the tradition and aims of those following it, from its origin in medieval Judaism to its later adaptations in Western esotericism. Jewish Kabbalah is a set of esoteric teachings meant to explain the relationship between the unchanging, eternal God—the mysterious Ein Sof —and the mortal, finite universe. It forms the foundation of mystical religious interpretations within Judaism.

The Zohar is a foundational work of Kabbalistic literature. It is a group of books including commentary on the mystical aspects of the Torah and scriptural interpretations as well as material on mysticism, mythical cosmogony, and mystical psychology. The Zohar contains discussions of the nature of God, the origin and structure of the universe, the nature of souls, redemption, the relationship of Ego to Darkness and "true self" to "The Light of God".

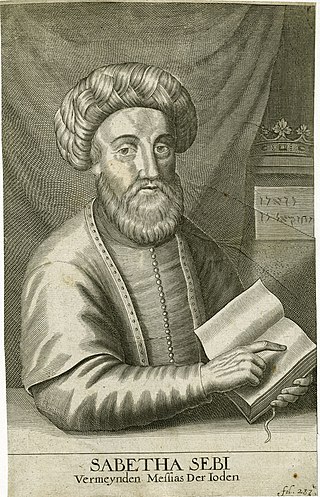

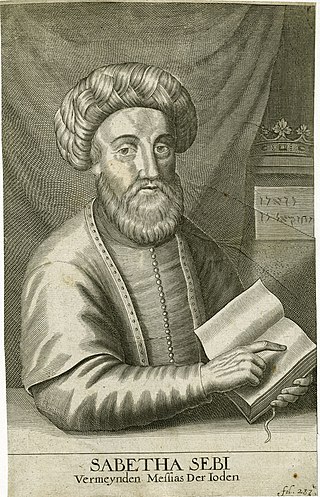

The Sabbateans were a variety of Jewish followers, disciples, and believers in Sabbatai Zevi (1626–1676), a Sephardic Jewish rabbi and Kabbalist who was proclaimed to be the Jewish Messiah in 1666 by Nathan of Gaza.

Sabbatai Zevi, was an Ottoman Jewish mystic, false messiah and ordained rabbi from Smyrna. He was likely of Ashkenazi origin. Active throughout the Ottoman Empire, Zevi claimed to be the long-awaited Jewish Messiah, and founded the Sabbatean movement.

Jacob Emden, also known as Ya'avetz, was a leading German rabbi and talmudist who championed Orthodox Judaism in the face of the growing influence of the Sabbatean movement. He was acclaimed in all circles for his extensive knowledge.

In Jewish law and history, Acharonim are the leading rabbis and poskim living from roughly the 16th century to the present, and more specifically since the writing of the Shulchan Aruch in 1563 CE.

Yechezkel ben Yehuda HaLevi Landau was an influential authority in halakha. He is best known for the work Noda Biyhudah, by which title he is also known.

Ein Sof, or Eyn Sof, in Kabbalah, is understood as God prior to any self-manifestation in the production of any spiritual realm, probably derived from Solomon ibn Gabirol's term, "the Endless One". Ein Sof may be translated as "unending", "(there is) no end", or infinity. It was first used by Azriel, who, sharing the Neoplatonic belief that God can have no desire, thought, word, or action, emphasized by it the negation of any attribute. Of the Ein Sof, nothing ("Ein") can be grasped ("Sof"-limitation). It is the origin of the Ohr Ein Sof, the "Infinite Light" of paradoxical divine self-knowledge, nullified within the Ein Sof prior to creation. In Lurianic Kabbalah, the first act of creation, the Tzimtzum self "withdrawal" of God to create an "empty space", takes place from there. In Hasidic Judaism, the Tzimtzum is only the illusionary concealment of the Ohr Ein Sof, giving rise to monistic panentheism. Consequently, Hasidism focuses on the Atzmus divine essence, rooted higher within the Godhead than the Ein Sof, which is limited to infinitude, and reflected in the essence (etzem) of the Torah and the soul.

Jonathan Eybeschutz was a Talmudist, Halachist, Kabbalist, holding positions as Dayan of Prague, and later as Rabbi of the "Three Communities": Altona, Hamburg and Wandsbek. He is well known for his conflict with Jacob Emden in the Emden–Eybeschutz Controversy.

Biala is a Hasidic dynasty originating from the city of Biała Rawska, where it was founded by R. Yaakov Yitzchak Rabinowicz (II). Biala is a branch of Peshischa Hasidism, as R. Yaakov Yitzchak Rabinowicz (II) was the great-grandson of R. Yaakov Yitzchak Rabinowicz, the first Peshischa Rebbe. The dynasty was originally spread throughout many towns in Poland, often taking the names of said towns. However, after the Holocaust, the name "Biala" become synonymous with the entire dynasty. Today the dynasty is mostly concentrated in Israel, America and Switzerland.

The Dönme were a group of Sabbatean crypto-Jews in the Ottoman Empire who converted outwardly to Islam, but retained their Jewish faith and Kabbalistic beliefs in secret. The movement was centered mainly in Thessaloniki. It originated during and soon after the era of Sabbatai Zevi, a 17th-century Sephardic Jewish Rabbi and Kabbalist who claimed to be the Jewish Messiah and eventually feigned conversion to Islam under threat of death from the Sultan Mehmed IV. After Zevi's forced conversion to Islam, a number of Sabbatean Jews purportedly converted to Islam and became the Dönme. Some Sabbateans lived on into 21st-century Turkey as descendants of the Dönme.

Nathan of Gaza, also Nathan Benjamin ben Elisha Hayyim haLevi Ashkenazi or Ghazzati, was a theologian and author born in Jerusalem. After his marriage in 1663 he moved to Gaza, where he became famous as a prophet for the Jewish messiah claimant Sabbatai Zevi.

Practical Kabbalah in historical Judaism, is a branch of the Jewish mystical tradition that concerns the use of magic. It was considered permitted white magic by its practitioners, reserved for the elite, who could separate its spiritual source from qlippoth realms of evil if performed under circumstances that were holy (Q-D-Š) and pure, tumah and taharah. The concern of overstepping Judaism's strong prohibitions of impure magic ensured it remained a minor tradition in Jewish history. Its teachings include the use of Divine and angelic names for amulets and incantations.

Komarno is a dynasty of Hasidic Judaism founded by Rabbi Aleksander Sender Safrin of Komarno, Ukraine.

Abraham Rovigo was a Jewish scholar, rabbi and kabbalist.

Meir bar Hiyya Rofe was a Hebron rabbi, known among other things for his tours of Europe as an emissary from the Holy Land on behalf of the Jewish community of Hebron. His father, Hiyya Rofe, was a very learned rabbi from Safed. Orphaned at a young age, Meir studied in Hebron, leaving about 1648 as an emissary to Italy, Holland, and Germany. On his return journey, he stayed for two years in Italy to publish Ma'aseh Ḥiyya, his father's talmudic novellae and responsa. In Amsterdam he had influenced the wealthy Abraham Pereyra to found a yeshiva in Hebron to be called Hesed le-Avraham, of which Meir himself became the head scholar.

Isaac Chelo, in Hebrew יצחק חילו, was a rabbi of the 14th century. His place of residence is unclear. Carmoly wrote "Laresa du royaume d'Aragon", which Scholem interpreted as an erroneous spelling of Lerida. However, Shapira took it to mean Larissa in Thessaly. Chelo is famous for an itinerary of the Holy Land first published in 1847. However, the document is now commonly considered a 19th-century forgery.

Israel Yaakov Algazi (1680–1757) was a Jewish rabbi of Izmir and Jerusalem, who served as Rishon Letzion for the last few years of his life.

References

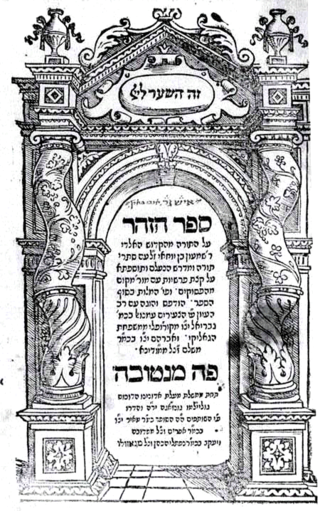

- ↑ The cover page of the third edition of the book contains (around the outside) verses which allude to Shabtai Zevi and his messianism.

- ↑ Moshe Fogel, "The Sabbatean-ness of the book Hemdat Yamim: A new consideration", The dream and its failure, the Sabbatean movement and its offshoots: messianism, Sabbateanism, and Frankism (ed. Rachel Elior), two volumes, Jerusalem: Department of Jewish thought, Institute for Jewish studies, Hebrew University of Jerusalem, 2001, p.365-422

- ↑ The history of Sabbateanism and its place in the life of Jews in the Ottoman Empire, Yaakov Barnai, p.64 and on

- 1 2 On the book Hemdat Yamim (by Yoel Rafel) - discussing the origins of Tu Bishvat, lays out the old disagreement, starting from Yaakov Emden's assertion that the author was Nathan of Gaza, and the disagreement of the professors Moshe Fogel (Hebrew University) who follows the view of Avraham Yaari that the sources are not Sabbatean, versus Boaz Huss (Ben Gurion University) who follows the view of Gershon Scholem and his student Isaiah Tishby, who wrote four articles arguing that the book consisted of Sabbatean sources.

- 1 2 3 "תעלומה ואין קורא לה? | קוֹנְדִיטוֹן". www.datshe.co.il. Archived from the original on 16 January 2014. Retrieved 15 January 2022.

- ↑ The relation of Hasidic greats to the book Hemdat Yamim

- ↑ On the book Hemdat Yamim and the Hasidic greats

- ↑ Jewish Encyclopedia: Israel Yaakov Algazi

- 1 2 The mystery of a book - the book Hemdat Yamim, who wrote it, and what was the amount of its influence, Avraham Yaari, Mossad Harav Kook, 1954

- ↑ Otzar Hemdat Yamim, 2008, Bnei Brak.

- ↑ Clarifying the arguments against the author of 'Hemdat Yamim'

- 1 2 And the mystery remains, Scholem's article opposing Yaari's opinion

- ↑ Chayei Adam, klal 144, se'if 20.

- ↑ ספר לשם שבו ואחלמה, ספר הדע"ה, דרושי עולם התוהו, ח"ב, דרוש ד', ענף כ"ד ס"ח בד"ה "והנה

- ↑ Kol Tzopayich, Behar-Bechukotai 2004