Related Research Articles

Simonne Monet-Chartrand was a Canadian labor activist, feminist writer, and pacifist.

Louise Saumoneau was a French feminist who later renounced feminism as being irrelevant to the class struggle. She became a union leader and a prominent socialist. During World War I she was active in the internationalist pacifist movement. In a change of stance, after the war she remained with the right of the socialist party after the majority split off to form the French Communist Party.

Louise Bodin was a French feminist and journalist who became a member of the steering committee of the French Communist Party.

Georges Jules Charles Pioch was a French poet, journalist, pacifist and socialist intellectual. He was president of the International League for Peace from 1930–37.

Marthe Bigot (1878–1962) was a French primary schoolteacher, feminist, pacifist and communist.

Madeleine Vernet was a French teacher, writer, libertarian and pacifist. She attacked abuses in the state system of foster homes, where children were often used for their labor. In 1906 she founded l'Avenir social, an orphanage for workers' children, which she ran despite government opposition until 1922, when she resigned after the board was taken over by Communists. She was a committed pacifist during World War I (1914–1918), and continued to be involved in pacifist organizations after the war.

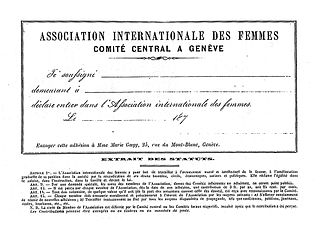

The Association internationale des femmes was a short-lived feminist and pacifist organization based in Geneva that was active between 1868 and 1872. It demanded full equality between men and women. This was too radical for many feminists at the time.

Hélène Brion was a French teacher, feminist, socialist and communist. She was one of the leaders of the French teachers' union. During World War I (1914–18) she was arrested for distributing pacifist propaganda, given a suspended sentence and dismissed from her job as a teacher. She visited Russia soon after the Russian Revolution, and wrote a book on her experiences. It was never published. She devoted much of her effort in later years to preparing a feminist encyclopedia, which was never completed or published.

Marianne Rauze was a French journalist, feminist, socialist, pacifist and communist.

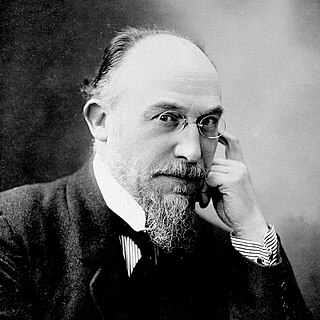

The Trois poèmes d'amour is a 1914 song cycle for voice and piano by Erik Satie. It is the only set of mélodies Satie composed to his own texts. The performance of the set lasts between 2 and 3 minutes.

Première femme de Chambre was an office at the royal court of France.

Louise Compain was a French novelist, journalist, freelance writer, feminist political activist, social reformer, and suffragist. She was the co-initiator of the feminist movement in France in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

Marie-Louise Globensky, Lady Lacoste, was a French-speaking Canadian philanthropist and diarist from the province of Quebec. She served as patroness for schools, orphans' homes, and several hospitals, including Sainte Justine, Hôpital Notre-Dame, and the Youville Foundling Hospital. Globensky was president of many benevolent societies, such as Château Ramezay and the Asile de la Providence. Appointed by her daughter Marie Lacoste Gérin-Lajoie, she served as vice-president of the Montreal Council of Women and supported women's suffrage, as long as social order was maintained. She also joined the National Federation of Saint John the Baptist, served on its board, and helped develop programs designed to help working women. A prolific diarist, her journals have contributed to the knowledge of how 19th-century middle-class women dealt with the social structures of their times.

The Paris Commune was an insurrectionary period in the history of Paris that lasted just over two months, from March 18, 1871, to the Semaine sanglante that ended on May 28, 1871. This insurrection refused to recognize the government of the National Assembly of 1871, which had just been elected by universal male suffrage. Many women took active roles in the events, and are known as "communardes". They are important in the history of women's rights in France, particularly with regards to women's emancipation. Equal pay and the first forms of structured organization of women in France appear during this period, in particular the Union des femmes pour la défense de Paris et les soins aux blessés or the Comité de vigilance de Montmartre.

Eugénie Hamer was a Belgian journalist, writer and activist. Her father and brother served in the Belgian military, but she was a committed pacifist. Involved in literary and women's social reform activities, she became one of the founders of the Alliance Belge pour la Paix par l'Éducation in 1906. The organization was founded in the belief that education, political neutrality, and women's suffrage were necessary components to peace. She was a participant in the 18th Universal Peace Congress held in Stockholm in 1910, the First National Peace Congress of Belgium held in 1913, and the Hague Conference of the International Congress of Women held in the Netherlands in 1915. This led to the creation of the International Committee of Women for Permanent Peace, subsequently known as the Women's International League for Peace and Freedom (WILPF). Hamer co-founded the Belgian chapter of the WILPF that same year. During World War I, she volunteered as a nurse and raised funds to acquire medical supplies and create an ambulance service.

Colette Reynaud (1872–1965) was a French feminist, socialist and pacifist journalist. In 1917, she was the co-founder and director of the weekly newspaper La Voix des femmes.

La Voix des femmes was a "political, social, scientific, artistic" weekly newspaper, founded in 1917 by Colette Reynaud and Louise Bodin, the first issue of which was published on October 31, 1917. The newspaper, which proclaimed itself in 1919 as "feminist, pacifist, socialist and internationalist", appeared until 1937.

Alice Jouenne was a French educator and socialist activist. During the interwar period, Jouenne focused on education, pacifism, and feminism. She was one of the founders of Éducation nouvelle en France.

Marie-Louise Bouglé was a French feminist, librarian, and archivist who founded a feminist library. The major themes of Archives Marie-Louise Bouglé are suffragism and pacifism. The collection is held by Bibliothèque historique de la ville de Paris.

Camille Drevet was a French anti-colonialist, feminist and pacifist activist. She was an important figure in the French section of the League against Imperialism. She served as international secretary of Women's International League for Peace and Freedom (LIFPL).

References

- ↑ Cross, Máire Fedelma (3 September 2020). In the Footsteps of Flora Tristan: A Political Biography. Liverpool University Press. p. 62. ISBN 978-1-78962-265-2. OCLC 1195464859.

- ↑ Stewart, Mary Lynn (20 June 2018). Gender, Generation, and Journalism in France, 1910-1940. McGill-Queen's Press - MQUP. p. 16. ISBN 978-0-7735-5402-3. OCLC 1035218064.

- 1 2 3 Quinn, P.; Trout, S., eds. (17 June 2001). The Literature of the Great War Reconsidered: Beyond Modern Memory. Springer. pp. 95, 101. ISBN 978-0-230-59989-5. OCLC 1022632853.

- 1 2 Higonnet, Margaret R., ed. (1999). Lines of Fire: Women Writers of World War I. Plume. p. 464. ISBN 978-0-452-28146-2. OCLC 1020204138.

- ↑ Ramsay, Raylene L. (2003). French Women in Politics: Writing Power: Paternal Legitimization and Maternal Legacies. Berghahn Books. pp. 104–. ISBN 978-1-57181-081-6. OCLC 1013441694.

- ↑ Sartori, Eva Martin; Zimmerman, Dorothy Wynne, eds. (1 January 1994). French Women Writers. University of Nebraska Press. p. 114. ISBN 978-0-8032-9224-6. OCLC 1027291730.

- ↑ Fell, A.; Sharp, I., eds. (12 April 2007). The Women's Movement in Wartime: International Perspectives, 1914-19. Springer. p. 89. ISBN 978-0-230-21079-0. OCLC 1047643539.

- ↑ Doy, Gen (13 August 2020). Claude Cahun: A Sensual Politics of Photography. Routledge. p. 225. ISBN 978-1-00-021343-0.

- 1 2 Potter, Caroline, ed. (13 May 2016). Erik Satie: Music, Art and Literature. Routledge. p. 69. ISBN 978-1-317-14179-2.

- ↑ Tamboukou, Maria (7 July 2016). Gendering the Memory of Work: Women Workers’ Narratives. Routledge. p. 30. ISBN 978-1-317-55226-0.

- ↑ Chadwick, Whitney; Latimer, Tirza True, eds. (2003). The Modern Woman Revisited: Paris Between the Wars. Rutgers University Press. pp. 67–69, 80, 87. ISBN 978-0-8135-3292-9. OCLC 1008050718.

- ↑ Kane, Nina; Woods, Jude, eds. (23 June 2017). Reflections on Female and Trans* Masculinities and Other Queer Crossings. Cambridge Scholars Publishing. p. 18. ISBN 978-1-4438-7797-8. OCLC 1327751175.