The Wright brothers, Orville Wright and Wilbur Wright, were American aviation pioneers generally credited with inventing, building, and flying the world's first successful airplane. They made the first controlled, sustained flight of an engine-powered, heavier-than-air aircraft with the Wright Flyer on December 17, 1903, four miles (6 km) south of Kitty Hawk, North Carolina, at what is now known as Kill Devil Hills. In 1904 the Wright brothers developed the Wright Flyer II, which made longer-duration flights including the first circle, followed in 1905 by the first truly practical fixed-wing aircraft, the Wright Flyer III.

Samuel Pierpont Langley was an American aviation pioneer, astronomer and physicist who invented the bolometer. He was the third secretary of the Smithsonian Institution and a professor of astronomy at the University of Pittsburgh, where he was the director of the Allegheny Observatory.

The history of aviation extends for more than two thousand years, from the earliest forms of aviation such as kites and attempts at tower jumping to supersonic and hypersonic flight by powered, heavier-than-air jets.

This is a list of aviation-related events from 1903:

Airplane inventors Wilbur and Orville Wright are famed for making the first controlled, powered, heavier-than-air flights on 17 December 1903 at Kitty Hawk, North Carolina. Lesser-known are other flights of theirs which played an important role at the dawn of aviation history. In 1909 Wilbur was invited by the Hudson-Fulton Celebration Committee to make paid exhibition flights to help mark 300 years of New York history, including Henry Hudson discovering Manhattan and Robert Fulton starting a successful commercial steamboat service on the Hudson River. The committee wanted the Wrights to demonstrate flights over the water around New York City. Orville was making flights for customers in Germany, so Wilbur, who had just finished training U.S. Army pilots, accepted the job.

Glenn Hammond Curtiss was an American aviation and motorcycling pioneer, and a founder of the U.S. aircraft industry. He began his career as a bicycle racer and builder before moving on to motorcycles. As early as 1904, he began to manufacture engines for airships. In 1908, Curtiss joined the Aerial Experiment Association, a pioneering research group, founded by Alexander Graham Bell at Beinn Bhreagh, Nova Scotia, to build flying machines.

Gustave Albin Whitehead was an aviation pioneer who emigrated from Germany to the United States where he designed and built gliders, flying machines, and engines between 1897 and 1915. Controversy surrounds published accounts and Whitehead's own claims that he flew a powered machine successfully several times in 1901 and 1902, predating the first flights by the Wright Brothers in 1903.

The June Bug was an American "pioneer era" biplane built by the Aerial Experiment Association (A.E.A) in 1908 and flown by Glenn Hammond Curtiss. The aircraft was the first American airplane to fly at least 1km in front of a crowd.

The Wright Flyer made the first sustained flight by a manned heavier-than-air powered and controlled aircraft—an airplane—on December 17, 1903. Invented and flown by brothers Orville and Wilbur Wright, it marked the beginning of the pioneer era of aviation.

The Wright Flyer III was the third powered aircraft by the Wright Brothers, built during the winter of 1904–05. Orville Wright made the first flight with it on June 23, 1905. The Wright Flyer III had an airframe of spruce construction with a wing camber of 1-in-20 as used in 1903, rather than the less effective 1-in-25 used in 1904. The new machine was equipped with the engine and other hardware from the scrapped Flyer II and, after major modifications, achieved much greater performance than Flyers I and II.

A steam-powered aircraft is an aircraft propelled by a steam engine. Steam power was used during the 19th century, but fell into disuse with the arrival of the more practical internal combustion engine at the beginning of the pioneer era.

The Manly–Balzer was the first purpose-designed aircraft engine, built in 1901 for the Langley Aerodrome project. The engine was originally ordered from Stephen Balzer (1864–1940) in New York, but his five-cylinder radial engine design failed to live up to its claims. Langley's chief assistant, Charles Manly, then reworked the engine to produce a design that held the record for power-to-weight ratio for any engine for many years. Manly later worked for Glenn Curtiss, and was one of the team-members who designed the mass-produced Curtiss OX-5.

The Langley Aerodrome was a pioneering but unsuccessful manned, tandem wing-configuration powered flying machine, designed at the close of the 19th century by Smithsonian Institution Secretary Samuel Langley. The U.S. Army paid $50,000 for the project in 1898 after Langley's successful flights with small-scale unmanned models two years earlier.

The Curtiss Flying School was started by Glenn Curtiss to compete against the Wright Flying School of the Wright brothers. The first example was located in San Diego, California.

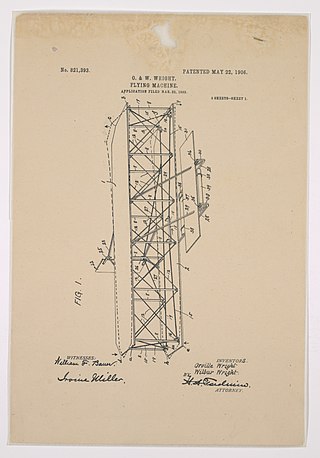

The Wright brothers patent war centers on the patent that the Wright brothers received for their method of airplane flight control. They were two Americans who are widely credited with inventing and building the world's first flyable airplane and making the first controlled, powered, and sustained heavier-than-air human flight on December 17, 1903.

The Langley Gold Medal, or Samuel P. Langley Medal for Aerodromics, is an award given by the Smithsonian Institution for outstanding contributions to the sciences of aeronautics and astronautics. Named in honor of Samuel P. Langley, the Smithsonian's third Secretary, it was authorized by the Board of Regents in 1909.

The Winds of Kitty Hawk is a 1978 American made-for-television biographical film directed by E. W. Swackhamer about the Wright brothers and their invention of the first successful powered heavier-than-air flying machine, the Wright Flyer. It's a tribute to the brothers and was broadcast on December 17, 1978, the 75th anniversary of their famous 1903 first aeroplane flight. It is one of several made-for-television films about historical people in aviation produced in the 1970s, including The Amazing Howard Hughes, Amelia Earhart, and The Lindbergh Kidnapping Case.

Several aviators have been claimed to be the first to fly a powered aeroplane. Much controversy surrounds these claims. It is generally accepted today that the Wright brothers were the first to achieve sustained and controlled powered manned flight, in 1903. It is popularly held in Brazil that their native citizen Alberto Santos-Dumont was the first successful aviator, discounting the Wright brothers' claim because their Flyer took off from a rail, and in later flights would sometimes employ a catapult. An editorial in the 2013 edition of Jane's All the World's Aircraft supported the claim of Gustave Whitehead. Claims by, or on behalf of, other pioneers such as Clément Ader have also been put forward from time to time.

Stanley Yale Beach was a wealthy aviation pioneer, who was an early financier of Gustave Whitehead, the contested first maker of a powered controlled flight before the Wright brothers. He was among the first technically trained men to be involved in dynamic flight in the United States, and was an early automobilist, following the beginnings of the development of the automobile industry as Automobile Editor of Scientific American, their family scientific magazine.