Mitanni, c. 1550–1260 BC, earlier called Ḫabigalbat in old Babylonian texts, c. 1600 BC; Hanigalbat or Hani-Rabbat in Assyrian records, or Naharin in Egyptian texts, was a Hurrian-speaking state in northern Syria and southeast Anatolia. Since no histories or royal annals/chronicles have yet been found in its excavated sites, knowledge about Mitanni is sparse compared to the other powers in the area, and dependent on what its neighbours commented in their texts.

Luwian, sometimes known as Luvian or Luish, is an ancient language, or group of languages, within the Anatolian branch of the Indo-European language family. The ethnonym Luwian comes from Luwiya – the name of the region in which the Luwians lived. Luwiya is attested, for example, in the Hittite laws.

Hattic, or Hattian, was a non-Indo-European agglutinative language spoken by the Hattians in Asia Minor in the 2nd millennium BC. Scholars call the language "Hattic" to distinguish it from Hittite, the Indo-European language of the Hittite Empire. The Hittites referred to the language as "hattili". The name is doubtlessly related to the Assyrian and Egyptian designation of an area west of the Euphrates as "Land of the Hatti" (Khatti).

Palaic is an extinct Indo-European language, attested in cuneiform tablets in Bronze Age Hattusa, the capital of the Hittites. Palaic, which was apparently spoken mainly in northern Anatolia, is generally considered to be one of four primary sub-divisions of the Anatolian languages, alongside Hittite, Luwic and Lydian.

Šarruma or Sharruma was a Hurrian mountain god, who was also worshipped by the Hittites and Luwians.

Kumarbi was an important god of the Hurrians, regarded as "the father of gods." He was also a member of the Hittite pantheon. According to Hurrian myths, he was a son of Alalu, and one of the parents of the storm-god Teshub, the other being Anu. His cult city was Urkesh.

Anitta, son of Pitḫana, reigned ca. 1740–1725 BC, and was a king of Kuššara, a city that has yet to be identified. He is the earliest known ruler to compose a text in the Hittite language.

Studien zu den Bogazköy-Texten edited by the German Akademie der Wissenschaften und der Literatur, Mainz, since 1965, is a series of editions of Hittite texts and monographs on topics of the Anatolian languages. The series was intended to publish the Hittite texts that were excavated at Hattusa.

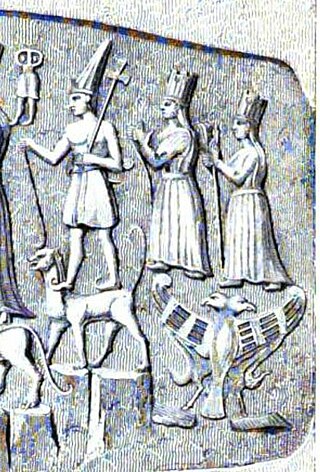

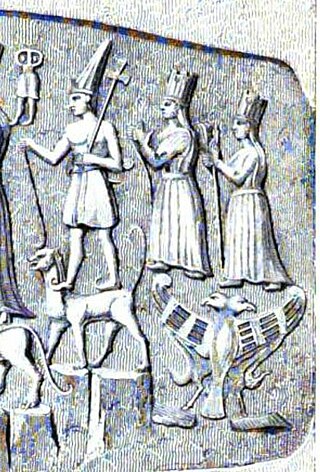

Hittite mythology and Hittite religion were the religious beliefs and practices of the Hittites, who created an empire centered in what is now Turkey from c. 1600–1180 BC.

Kikkuli was the Hurrian "master horse trainer [assussanni] of the land of Mitanni" and author of a chariot horse training text written primarily in the Hittite language, dating to the Hittite New Kingdom. The text is notable both for the information it provides about the development of Indo-European languages and for its content. The text was inscribed on cuneiform tablets discovered during excavations of Boğazkale and Ḫattuša in 1906 and 1907.

Prof. Ord. Sedat Alp was the first Turkish archaeologist, historian and academic with a specialization in Hittitology, and was among the foremost names in the field. He was the president of the Turkish Historical Association from 1982 to 1983.

Ammurapi was the last Bronze Age ruler and king of the ancient Syrian city of Ugarit. Ammurapi was a contemporary of the Hittite King Suppiluliuma II. He wrote a preserved vivid letter RS 18.147 in response to a plea for assistance from the king of Alashiya.

Emmanuel Laroche was a French linguist and Hittitologist. An expert in the languages of ancient Anatolia, he was professor of Anatolian studies at the Collège de France (1973–1985).

Aruna was the god of the sea in Hittite religion. His name is identical with the Hittite word for the sea, which could also refer to bodies of water, treated as numina rather than personified deities. His worship was not widespread, and most of the known attestations of it come exclusively from the southeast of Anatolia. He was celebrated in cities such as Ḫubešna and Tuwanuwa.

The Sun goddess of Arinna, also sometimes identified as Arinniti or as Wuru(n)šemu, is the chief goddess and companion of the weather god Tarḫunna in Hittite mythology. She protected the Hittite kingdom and was called the "Queen of all lands." Her cult centre was the sacred city of Arinna.

Takitu, Takiti or Daqitu was a Hurrian goddess who served as the sukkal of Ḫepat. She appears alongside her mistress in a number of Hurrian myths, in which she is portrayed as her closest confidante. Her name is usually assumed to have its origin in a Semitic language, though a possible Hurrian etymology has also been proposed. She was worshiped in Hattusa, Lawazantiya and Ugarit.

Ziparwa, originally known as Zaparwa, was the head of the pantheon of the Palaians, inhabitants of a region of northern Anatolia known as Pala in the Bronze Age. It is often assumed that he was a weather god in origin, though he was also associated with vegetation. Information about the worship of Ziparwa comes exclusively from Hittite texts, though some of them indicate that formulas in Palaic were used during festivals dedicated to him held in Hittite cities such as Hattusa.

Iyaya was a Hittite and Luwian goddess. Her functions remain uncertain, though it has been suggested she was associated with water or more broadly with nature. She might have been associated with the god Šanta, though the available evidence is limited. Her main cult centers were Lapana and Tiura, though she was also worshiped in other cities.

Uršui or Uršue was a Hurrian goddess. Her name might be derived from the toponym Uršu. It is not certain if the also attested name Uršui-Iškalli should be interpreted as Uršui's name being used as an epithet, as her name accompanied by epithet, or as a pair of goddesses. In Hurrian offering lists, appears as a member of the circle of either Ḫepat or Šauška.