In Greek mythology, Achilles or Achilleus was a hero of the Trojan War who was known as being the greatest of all the Greek warriors. A central character in Homer's Iliad, he was the son of the Nereid Thetis and Peleus, king of Phthia and famous Argonaut. Achilles was raised in Phthia along with his childhood companion Patroclus and received his education by the centaur Chiron. In the Iliad, he is presented as the commander of the mythical tribe of the Myrmidons.

Athena or Athene, often given the epithet Pallas, is an ancient Greek goddess associated with wisdom, warfare, and handicraft who was later syncretized with the Roman goddess Minerva. Athena was regarded as the patron and protectress of various cities across Greece, particularly the city of Athens, from which she most likely received her name. The Parthenon on the Acropolis of Athens is dedicated to her. Her major symbols include owls, olive trees, snakes, and the Gorgoneion. In art, she is generally depicted wearing a helmet and holding a spear.

In the ancient Greek myths, ambrosia is the food or drink of the Greek gods, and is often depicted as conferring longevity or immortality upon whoever consumed it. It was brought to the gods in Olympus by doves and served either by Hebe or by Ganymede at the heavenly feast.

In ancient Greek religion, Hera is the goddess of marriage, women, and family, and the protector of women during childbirth. In Greek mythology, she is queen of the twelve Olympians and Mount Olympus, sister and wife of Zeus, and daughter of the Titans Cronus and Rhea. One of her defining characteristics in myth is her jealous and vengeful nature in dealing with any who offended her, especially Zeus's numerous adulterous lovers and illegitimate offspring.

Hades, in the ancient Greek religion and mythology, is the god of the dead and the king of the underworld, with which his name became synonymous. Hades was the eldest son of Cronus and Rhea, although this also made him the last son to be regurgitated by his father. He and his brothers, Zeus and Poseidon, defeated their father's generation of gods, the Titans, and claimed joint rulership over the cosmos. Hades received the underworld, Zeus the sky, and Poseidon the sea, with the solid earth available to all three concurrently. In artistic depictions, Hades is typically portrayed holding a bident and wearing his helm with Cerberus, the three-headed guard-dog of the underworld, standing at his side.

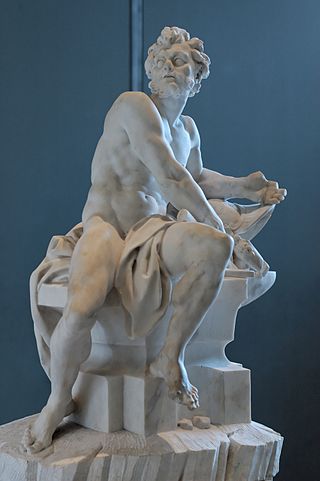

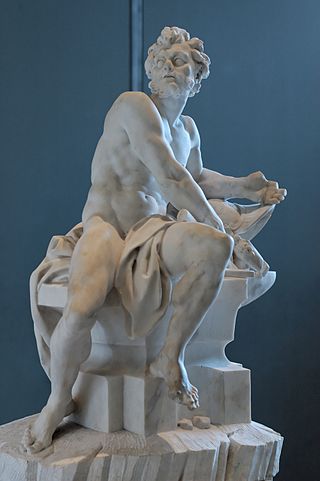

Hephaestus is the Greek god of artisans, blacksmiths, carpenters, craftsmen, fire, metallurgy, metalworking, sculpture and volcanoes. Hephaestus's Roman counterpart is Vulcan. In Greek mythology, Hephaestus was either the son of Zeus and Hera or he was Hera's parthenogenous child. He was cast off Mount Olympus by his mother Hera because of his lameness, the result of a congenital impairment; or in another account, by Zeus for protecting Hera from his advances.

The Trojan War was a legendary conflict in Greek mythology that took place around the 12th or 13th century BCE. The war was waged by the Achaeans (Greeks) against the city of Troy after Paris of Troy took Helen from her husband Menelaus, king of Sparta. The war is one of the most important events in Greek mythology, and it has been narrated through many works of Greek literature, most notably Homer's Iliad. The core of the Iliad describes a period of four days and two nights in the tenth year of the decade-long siege of Troy; the Odyssey describes the journey home of Odysseus, one of the war's heroes. Other parts of the war are described in a cycle of epic poems, which have survived through fragments. Episodes from the war provided material for Greek tragedy and other works of Greek literature, and for Roman poets including Virgil and Ovid.

In ancient Greek religion and mythology, Hestia is the virgin goddess of the hearth and the home. In myth, she is the firstborn child of the Titans Cronus and Rhea, and one of the Twelve Olympians.

Thetis is a figure from Greek mythology with varying mythological roles. She mainly appears as a sea nymph, a goddess of water, and one of the 50 Nereids, daughters of the ancient sea god Nereus.

Diomedes or Diomede is a hero in Greek mythology, known for his participation in the Trojan War.

Religious practices in ancient Greece encompassed a collection of beliefs, rituals, and mythology, in the form of both popular public religion and cult practices. The application of the modern concept of "religion" to ancient cultures has been questioned as anachronistic. The ancient Greeks did not have a word for 'religion' in the modern sense. Likewise, no Greek writer known to us classifies either the gods or the cult practices into separate 'religions'. Instead, for example, Herodotus speaks of the Hellenes as having "common shrines of the gods and sacrifices, and the same kinds of customs."

In ancient Greek religion and mythology, the twelve Olympians are the major deities of the Greek pantheon, commonly considered to be Zeus, Poseidon, Hera, Demeter, Aphrodite, Athena, Artemis, Apollo, Ares, Hephaestus, Hermes, and either Hestia or Dionysus. They were called Olympians because, according to tradition, they resided on Mount Olympus.

The ancient Greeks had numerous water deities. The philosopher Plato once remarked that the Greek people were like frogs sitting around a pond—their many cities hugging close to the Mediterranean coastline from the Hellenic homeland to Asia Minor, Libya, Sicily, and southern Italy. Thus, they venerated a rich variety of water divinities. The range of Greek water deities of the classical era range from primordial powers and an Olympian on the one hand, to heroized mortals, chthonic nymphs, trickster-figures, and monsters on the other.

The Aethiopis, also spelled Aithiopis, is a lost epic of ancient Greek literature. It was one of the Epic Cycle, that is, the Trojan cycle, which told the entire history of the Trojan War in epic verse. The story of the Aethiopis comes chronologically immediately after that of the Homeric Iliad, and is followed by that of the Little Iliad. The Aethiopis was sometimes attributed by ancient writers to Arctinus of Miletus. The poem comprised five books of verse in dactylic hexameter.

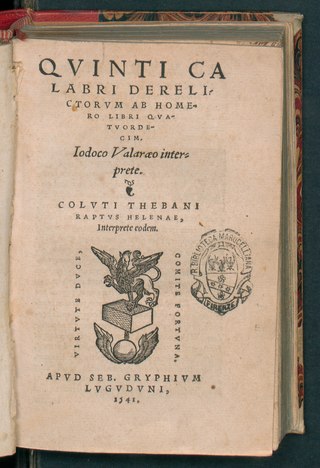

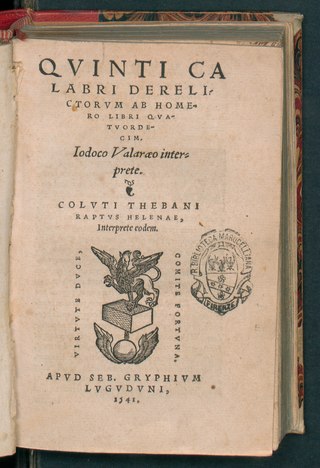

The Posthomerica is an epic poem in Greek hexameter verse by Quintus of Smyrna. Probably written in the 3rd century AD, it tells the story of the Trojan War, between the death of Hector and the fall of Ilium. The poem is an abridgement of the epic poems Aethiopis and Iliou Persis by Arctinus of Miletus, and the Little Iliad by Lesches, all now-lost poems of the Epic Cycle.

The Odyssean gods are the ancient Greek gods referenced in Homer's Odyssey.

The Returns from Troy are the stories of how the Greek leaders returned after their victory in the Trojan War. Many Achaean heroes did not return to their homes, but died or founded colonies outside the Greek mainland. The most famous returns are those of Odysseus, whose wanderings are narrated in the Odyssey, and Agamemnon, whose murder at the hands of his wife Clytemnestra was portrayed in Greek tragedy.

The Iliad is one of two major ancient Greek epic poems attributed to Homer. It is one of the oldest extant works of literature still widely read by modern audiences. As with the Odyssey, the poem is divided into 24 books and was written in dactylic hexameter. It contains 15,693 lines in its most widely accepted version. Set towards the end of the Trojan War, a ten-year siege of the city of Troy by a coalition of Mycenaean Greek states, the poem depicts significant events in the siege's final weeks. In particular, it depicts a fierce quarrel between King Agamemnon and a celebrated warrior, Achilles. It is a central part of the Epic Cycle. The Iliad is often regarded as the first substantial piece of European literature.

Jørgensen's law is a principle of narration in Homeric poetry first proposed by the Danish classicist Ove Jørgensen in 1904. According to Jørgensen's law, mortal characters in the Homeric poems are generally unaware of the precise actions of the gods, unless possessed of special powers, and so attribute them generically to "the gods", Zeus, or generalised forces. The narrator and the gods themselves, meanwhile, invariably name the specific god involved, making the audience aware immediately of the true nature of divine action.