Related Research Articles

A copyright is a type of intellectual property that gives its owner the exclusive legal right to copy, distribute, adapt, display, and perform a creative work, usually for a limited time. The creative work may be in a literary, artistic, educational, or musical form. Copyright is intended to protect the original expression of an idea in the form of a creative work, but not the idea itself. A copyright is subject to limitations based on public interest considerations, such as the fair use doctrine in the United States and fair dealings doctrine in the United Kingdom.

A performance rights organisation (PRO), also known as a performing rights society, provides intermediary functions, particularly collection of royalties, between copyright holders and parties who wish to use copyrighted works publicly in locations such as shopping and dining venues. Legal consumer purchase of works, such as buying CDs from a music store, confer private performance rights. PROs usually only collect royalties when use of a work is incidental to an organisation's purpose. Royalties for works essential to an organisation's purpose, such as theaters and radio, are usually negotiated directly with the rights holder. The interest of the organisations varies: many have the sole focus of musical works, while others may also encompass works and authors for audiovisual, drama, literature, or the visual arts.

Reproduction fees are charged by image collections for the right to reproduce images in publications. This is not the same as a copyright fee, but is charged separately, as is the cost of the provision of the image. It can be charged where an image is out of copyright, and reflects the possession of the image by a collection.

An orphan work is a copyright-protected work for which rightsholders are positively indeterminate or uncontactable. Sometimes the names of the originators or rightsholders are known, yet it is impossible to contact them because additional details cannot be found. A work can become orphaned through rightsholders being unaware of their holding, or by their demise and establishing inheritance has proved impracticable. In other cases, comprehensively diligent research fails to determine any authors, creators or originators for a work. Since 1989, the amount of orphan works in the United States has increased dramatically since some works are published anonymously, assignments of rights are not required to be disclosed publicly, and registration is optional. As a result, many works' statuses with respect to who holds which rights remain unknown to the public even when those rights are being actively exploited by authors or other rightsholders.

Bridgeman Images, based in New York, London, Paris and Berlin, provides one of the largest archives for reproductions of works of art in the world. Bridgeman Art Library was founded in 1972 by Harriet Bridgeman and changed its name in 2014. The Bridgeman Art Library works with art galleries and museums to gather images and footage for licensing.

Copyright in the Netherlands is governed by the Dutch Copyright Law, copyright is the exclusive right of the author of a work of literature or artistic work to publish and copy such work.

A replica is an exact copy or remake of an object, made out of the same raw materials, whether a molecule, a work of art, or a commercial product. The term is also used for copies that closely resemble the original, without claiming to be identical. Copies or reproductions of documents, books, manuscripts, maps or art prints are called facsimiles.

In Germany, photo rights or "Bildrechte" are the copyrights that are attached to the "author" of the photograph and are specified in the "Law for Copyright and similar Protection". These rights deal with rights of reproduction, distribution, modification, attribution, and prohibitions against illegal modification or reproduction. The ownership rights of a picture are treated under the broader "art copyright laws". Furthermore, if a museum or gallery owns a work of art or a photograph, they are permitted to make their own stipulations as to the selling of illustrations and reproductions of their property. This relates to the German legal concept of the right of owner to undisturbed possession. Wolf Vostell said: "Copyrights are like human rights".

The Jordanian Copyright Law and its Amendment No. (22) for the year 1992 is based on the Berne Convention for the Protection of Literary and Artistic Works and does not contain a definition of copyright; however in Article (3) it clearly states that the law offers legal protection to any kind of original work in literature, art and science regardless of the value or purpose of the work.

Spanish copyright law, or authors' right law, governs intellectual property rights that authors have over their original literary, artistic or scientific works in Spain. It was first instituted by the Law of 10 January 1879, and, in its origins, was influenced by French authors' right law and by the movement led by Victor Hugo for the international protection of literary and artistic works. As of 2006, the principal dispositions are contained in Book One of the Intellectual Property Law of 11 November 1987 as modified. A consolidated version of this law was approved by Royal Legislative Decree 1/1996 of 12 April 1996: unless otherwise stated, all references are to this law.

Public domain music is music to which no exclusive intellectual property rights apply.

A copyfraud is a false copyright claim by an individual or institution with respect to content that is in the public domain. Such claims are unlawful, at least under US and Australian copyright law, because material that is not copyrighted is free for all to use, modify and reproduce. Copyfraud also includes overreaching claims by publishers, museums and others, as where a legitimate copyright owner knowingly, or with constructive knowledge, claims rights beyond what the law allows.

Sweat of the brow is a copyright law doctrine. According to this doctrine, an author gains rights through simple diligence during the creation of a work, such as a database, or a directory. Substantial creativity or "originality" is not required.

Freedom of panorama (FoP) is a provision in the copyright laws of various jurisdictions that permits taking photographs and video footage and creating other images of buildings and sometimes sculptures and other art works which are permanently located in a public space, without infringing on any copyright that may otherwise subsist in such works, and the publishing of such images. Panorama freedom statutes or case law limit the right of the copyright owner to take action for breach of copyright against the creators and distributors of such images. It is an exception to the normal rule that the copyright owner has the exclusive right to authorize the creation and distribution of derivative works.

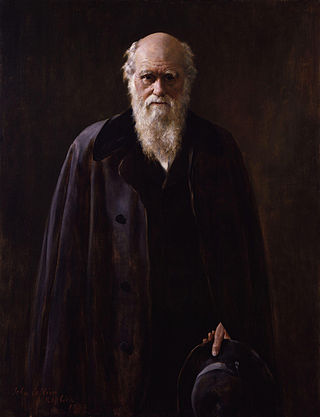

Bridgeman Art Library v. Corel Corp., 36 F. Supp. 2d 191, was a decision by the United States District Court for the Southern District of New York, which ruled that exact photographic copies of public domain images could not be protected by copyright in the United States because the copies lack originality. Even though accurate reproductions might require a great deal of skill, experience, and effort, the key element to determine whether a work is copyrightable under US law is originality.

The public domain (PD) consists of all the creative work to which no exclusive intellectual property rights apply. Those rights may have expired, been forfeited, expressly waived, or may be inapplicable. Because no one holds the exclusive rights, anyone can legally use or reference those works without permission.

The copyright law of the United States grants monopoly protection for "original works of authorship". With the stated purpose to promote art and culture, copyright law assigns a set of exclusive rights to authors: to make and sell copies of their works, to create derivative works, and to perform or display their works publicly. These exclusive rights are subject to a time and generally expire 70 years after the author's death or 95 years after publication. In the United States, works published before January 1, 1930, are in the public domain.

In July 2009, lawyers representing the British National Portrait Gallery (NPG) sent an email letter warning of possible legal action for alleged copyright infringement to Derrick Coetzee, an editor/administrator of the free content multimedia repository Wikimedia Commons, hosted by the Wikimedia Foundation (WMF), after Coetzee uploaded more than 3,300 high-resolution images of artworks, taken from the NPG website, to Wikimedia Commons.

The basic legal instrument governing copyright law in Georgia is the Law on Copyright and Neighboring Rights of June 22, 1999 replacing Art. 488–528 of the Georgian Civil Code of 1964. While the old law had followed the Soviet Fundamentals of 1961, the new law is largely influenced by the copyright law of the European Union.

Controlled digital lending (CDL) is a model by which libraries digitize materials in their collection and make them available for lending. It is based on interpretations of the United States copyright principles of fair use and copyright exhaustion.

References

Citations

- 1 2 Frye 2022, p. 180.

- ↑ Frye 2022, p. 182.

- ↑ Milone 1995, p. 396.

- ↑ Butler 1998, p. 72.

- ↑ Appel 1999, p. 180.

- ↑ Bertacchini & Morando 2011, p. 6.

- 1 2 Butler 1998, p. 68.

- ↑ Butler 1998, pp. 69–71.

- ↑ Frye 2022, p. 178.

- ↑ Frye 2022, pp. 178–179.

- ↑ Frye 2022, pp. 180–181.

- ↑ Frye 2022, p. 181.

- ↑ Bertacchini & Morando 2011, p. 8.

- ↑ Allan 2007, p. 962.

- ↑ Petri 2014, pp. 7–8.

- ↑ Petri 2014, p. 8.

- ↑ Sappa & Bossi 2024, p. 3.

- ↑ Sappa & Bossi 2024, pp. 1, 11–12.

Sources

- Allan, Robin J. (2007). "After Bridgeman: Copyright, Museums, and Public Domain Works of Art". University of Pennsylvania Law Review. 155: 961–989.

- Appel, Sharon (1999). "Copyright, Digitization of Images, and Art Museums: Cyberspace and Other New Frontiers" (PDF). UCLA Entertainment Law Review. 6 (2). doi: 10.5070/LR862026984 . ISSN 1939-5523 . Retrieved 2 January 2025.

- Bertacchini, Enrico; Morando, Federico (2011). "The Future of Museums in the Digital Age: New Models of Access and Use of Digital Collections" (PDF). EBLA Working Papers. University of Turin.

- Butler, Kathleen Connolly (1998). "Keeping the World Safe from Naked-Chicks-in-Art Refigerator Magnets: The Plot to Control Art Images in the Public Domain through Copyrights in Photographic and Digital Reproductions". Hastings Communications & Enterprise Law Journal. 55.

- Frye, Brian L. (2022). "Image Reproduction Rights in a Nutshell for Art Historians" (PDF). IDEA . 62 (175): 175–205. doi:10.2139/ssrn.3755966.

- Marciano, Alain; Moureau, Nathalie (2016). "Museums, Property Rights, and Photographs of Works of Art. Why Reproduction through Photograph Should Be Free". Review of Economics Research on Copyright Issues. 13. SSRN 2840305.

- Milone, Kim L. (2 January 1995). "Dithering Over Digitization: International Copyright and Licensing Agreements between Museums, Artists, and New Media Publishers" (PDF). Indiana International & Comparative Law Review. 5 (2): 393–424. doi:10.18060/17575. ISSN 2169-3226.

- Petri, Grischka (28 August 2014). "The Public Domain vs. the Museum: The Limits of Copyright and Reproductions of Two-dimensional Works of Art". Journal of Conservation and Museum Studies. 12 (1). doi: 10.5334/jcms.1021217 . ISSN 1364-0429.

- Sappa, Cristiana; Bossi, Ludovico (2024). "Postcards from Italy. The art of controlling cultural goods' images better than copyright could". SSRN Electronic Journal. doi:10.2139/ssrn.4967818. ISSN 1556-5068. SSRN 4967818.