Related Research Articles

Catalysis is the process of increasing the rate of a chemical reaction by adding a substance known as a catalyst. Catalysts are not consumed by the reaction and remain unchanged after it. If the reaction is rapid and the catalyst recycles quickly, very small amounts of catalyst often suffice; mixing, surface area, and temperature are important factors in reaction rate. Catalysts generally react with one or more reactants to form intermediates that subsequently give the final reaction product, in the process of regenerating the catalyst.

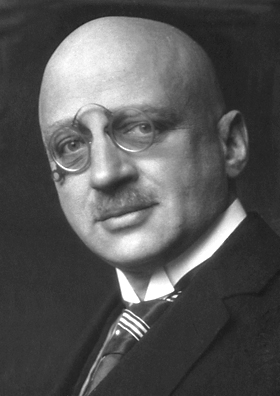

The Haber process, also called the Haber–Bosch process, is the main industrial procedure for the production of ammonia. It is named after its inventors, the German chemists: Fritz Haber and Carl Bosch, who developed it in the first decade of the 20th century. The process converts atmospheric nitrogen (N2) to ammonia (NH3) by a reaction with hydrogen (H2) using a metal catalyst under high temperatures and pressures. This reaction is slightly exothermic (i.e. it releases energy), meaning that the reaction is favoured at lower temperatures and higher pressures. It decreases entropy, complicating the process. Hydrogen is produced via steam reforming, followed by an iterative closed cycle to react hydrogen with nitrogen to produce ammonia.

A Ziegler–Natta catalyst, named after Karl Ziegler and Giulio Natta, is a catalyst used in the synthesis of polymers of 1-alkenes (alpha-olefins). Two broad classes of Ziegler–Natta catalysts are employed, distinguished by their solubility:

Zeolites are microporous, crystalline aluminosilicate materials commonly used as commercial adsorbents and catalysts. They mainly consist of silicon, aluminium, oxygen, and have the general formula Mn+

1/n(AlO

2)−

(SiO

2)

x・yH

2O where Mn+

1/n is either a metal ion or H+. These positive ions can be exchanged for others in a contacting electrolyte solution. H+

exchanged zeolites are particularly useful as solid acid catalysts.

Sintering or frittage is the process of compacting and forming a solid mass of material by pressure or heat without melting it to the point of liquefaction.

Adsorption is the adhesion of atoms, ions or molecules from a gas, liquid or dissolved solid to a surface. This process creates a film of the adsorbate * on the surface of the adsorbent(solvent). This process differs from absorption, in which a fluid is dissolved by or permeates a liquid or solid. Adsorption is a surface phenomenon and does not penetrate through the surface to the bulk of the adsorbent, while absorption involves the whole volume of the material, although adsorption does often precede absorption. The term sorption encompasses both processes, while desorption is the reverse of it.

Potassium hydroxide is an inorganic compound with the formula KOH, and is commonly called caustic potash.

Hydrogenation is a chemical reaction between molecular hydrogen (H2) and another compound or element, usually in the presence of a catalyst such as nickel, palladium or platinum. The process is commonly employed to reduce or saturate organic compounds. Hydrogenation typically constitutes the addition of pairs of hydrogen atoms to a molecule, often an alkene. Catalysts are required for the reaction to be usable; non-catalytic hydrogenation takes place only at very high temperatures. Hydrogenation reduces double and triple bonds in hydrocarbons.

Zinc chloride is the name of inorganic chemical compounds with the formula ZnCl2. It forms hydrates. Zinc chloride, anhydrous and its hydrates are colorless or white crystalline solids, and are highly soluble in water. Five hydrates of zinc chloride are known, as well as four forms of anhydrous zinc chloride. This salt is hygroscopic and even deliquescent. Zinc chloride finds wide application in textile processing, metallurgical fluxes, and chemical synthesis. No mineral with this chemical composition is known aside from the very rare mineral simonkolleite, Zn5(OH)8Cl2·H2O.

The Fischer–Tropsch process is a collection of chemical reactions that converts a mixture of carbon monoxide and hydrogen, known as syngas, into liquid hydrocarbons. These reactions occur in the presence of metal catalysts, typically at temperatures of 150–300 °C (302–572 °F) and pressures of one to several tens of atmospheres. The Fischer–Tropsch process is an important reaction in both coal liquefaction and gas to liquids technology for producing liquid hydrocarbons.

In chemistry, heterogeneous catalysis is catalysis where the phase of catalysts differs from that of the reactants or products. The process contrasts with homogeneous catalysis where the reactants, products and catalyst exist in the same phase. Phase distinguishes between not only solid, liquid, and gas components, but also immiscible mixtures, or anywhere an interface is present.

Raney nickel, also called spongy nickel, is a fine-grained solid composed mostly of nickel derived from a nickel–aluminium alloy. Several grades are known, of which most are gray solids. Some are pyrophoric, but most are used as air-stable slurries. Raney nickel is used as a reagent and as a catalyst in organic chemistry. It was developed in 1926 by American engineer Murray Raney for the hydrogenation of vegetable oils. Raney is a registered trademark of W. R. Grace and Company. Other major producers are Evonik and Johnson Matthey.

Chloroplatinic acid (also known as hexachloroplatinic acid) is an inorganic compound with the formula [H3O]2[PtCl6](H2O)x (0 ≤ x ≤ 6). A red solid, it is an important commercial source of platinum, usually as an aqueous solution. Although often written in shorthand as H2PtCl6, it is the hydronium (H3O+) salt of the hexachloroplatinate anion (PtCl2−

6). Hexachloroplatinic acid is highly hygroscopic.

The pore space of soil contains the liquid and gas phases of soil, i.e., everything but the solid phase that contains mainly minerals of varying sizes as well as organic compounds.

Isopropyl alcohol is a colorless, flammable organic compound with a pungent alcoholic odor. As an isopropyl group linked to a hydroxyl group it is the simplest example of a secondary alcohol, where the alcohol carbon atom is attached to two other carbon atoms. It is a structural isomer of propan-1-ol and ethyl methyl ether. They all have the formula C3H8O.

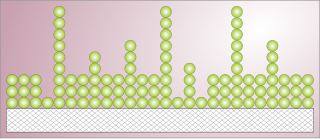

In chemistry, a catalyst support is the material, usually a solid with a high surface area, to which a catalyst is affixed. The activity of heterogeneous catalysts is mainly promoted by atoms present at the accessible surface of the material. Consequently, great effort is made to maximize the specific surface area of a catalyst. One popular method for increasing surface area involves distributing the catalyst over the surface of the support. The support may be inert or participate in the catalytic reactions. Typical supports include various kinds of activated carbon, alumina, and silica.

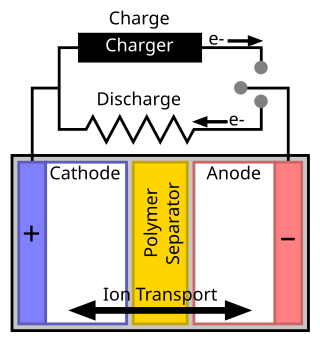

A separator is a permeable membrane placed between a battery's anode and cathode. The main function of a separator is to keep the two electrodes apart to prevent electrical short circuits while also allowing the transport of ionic charge carriers that are needed to close the circuit during the passage of current in an electrochemical cell.

The Stöber process is a chemical process used to prepare silica particles of controllable and uniform size for applications in materials science. It was pioneering when it was reported by Werner Stöber and his team in 1968, and remains today the most widely used wet chemistry synthetic approach to silica nanoparticles. It is an example of a sol-gel process wherein a molecular precursor is first reacted with water in an alcoholic solution, the resulting molecules then joining together to build larger structures. The reaction produces silica particles with diameters ranging from 50 to 2000 nm, depending on conditions. The process has been actively researched since its discovery, including efforts to understand its kinetics and mechanism – a particle aggregation model was found to be a better fit for the experimental data than the initially hypothesized LaMer model. The newly acquired understanding has enabled researchers to exert a high degree of control over particle size and distribution and to fine-tune the physical properties of the resulting material in order to suit intended applications.

Aerogels are a class of synthetic porous ultralight material derived from a gel, in which the liquid component for the gel has been replaced with a gas, without significant collapse of the gel structure. The result is a solid with extremely low density and extremely low thermal conductivity. Aerogels can be made from a variety of chemical compounds. Silica aerogels feel like fragile expanded polystyrene to the touch, while some polymer-based aerogels feel like rigid foams.

Solvated Metal Atom Dispersion is a method of producing highly reactive solvated nanoparticles. Samples of a metal (or ceramic) are heated to evaporate free atoms (or species), as in PVD evaporation. This vapor is then co-deposited with a suitable organic solvent (e.g. toluene) at very low temperatures (on the order of 70K) to form a solid mixture of the two. This is then warmed towards room temperature, producing solvated metal atoms or (over time) larger clusters. Sometimes, catalyst supports (such as SiO2 or Al2O3) are added to improve nucleation, as the process can more readily take place on surface OH groups.

References

- de Jong, Krijn (2009). Synthesis of Solid Catalysts. Wiley. ISBN 978-3-527-32040-0.

- Regalbuto, John (2007). Catalyst Preparation: Science and Engineering. CRC Press. ISBN 978-0-8493-7088-5.

- Ertl, Gerhard; Knözinger, Helmut; Weitkamp, Jens (1999). Preparation of Solid Catalysts. Wiley. ISBN 978-3-527-29826-6.