Related Research Articles

Cognitive science is the interdisciplinary, scientific study of the mind and its processes. It examines the nature, the tasks, and the functions of cognition. Mental faculties of concern to cognitive scientists include language, perception, memory, attention, reasoning, and emotion; to understand these faculties, cognitive scientists borrow from fields such as linguistics, psychology, artificial intelligence, philosophy, neuroscience, and anthropology. The typical analysis of cognitive science spans many levels of organization, from learning and decision to logic and planning; from neural circuitry to modular brain organization. One of the fundamental concepts of cognitive science is that "thinking can best be understood in terms of representational structures in the mind and computational procedures that operate on those structures."

Consciousness, at its simplest, is awareness of internal and external existence. However, its nature has led to millennia of analyses, explanations, and debate by philosophers, scientists, and theologians. Opinions differ about what exactly needs to be studied or even considered consciousness. In some explanations, it is synonymous with the mind, and at other times, an aspect of it. In the past, it was one's "inner life", the world of introspection, of private thought, imagination, and volition. Today, it often includes any kind of cognition, experience, feeling or perception. It may be awareness, awareness of awareness, metacognition, or self-awareness either continuously changing or not. The disparate range of research, notions and speculations raises a curiosity about whether the right questions are being asked.

The Chinese room argument holds that a computer executing a program cannot have a mind, understanding, or consciousness, regardless of how intelligently or human-like the program may make the computer behave. The argument was presented in a 1980 paper by the philosopher John Searle entitled "Minds, Brains, and Programs" and published in the journal Behavioral and Brain Sciences. Before Searle, similar arguments had been presented by figures including Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz (1714), Anatoly Dneprov (1961), Lawrence Davis (1974) and Ned Block (1978). Searle's version has been widely discussed in the years since. The centerpiece of Searle's argument is a thought experiment known as the Chinese room.

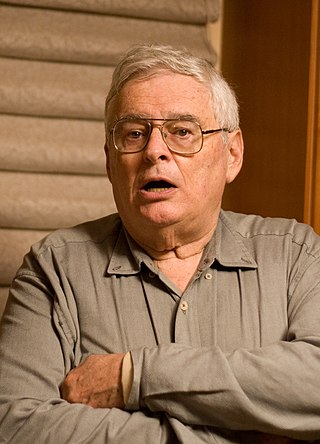

Daniel Clement Dennett III was an American philosopher and cognitive scientist. His research centered on the philosophy of mind, the philosophy of science, and the philosophy of biology, particularly as those fields relate to evolutionary biology and cognitive science.

Consciousness Explained is a 1991 book by the American philosopher Daniel Dennett, in which the author offers an account of how consciousness arises from interaction of physical and cognitive processes in the brain. Dennett describes consciousness as an account of the various calculations occurring in the brain at close to the same time. He compares consciousness to an academic paper that is being developed or edited in the hands of multiple people at one time, the "multiple drafts" theory of consciousness. In this analogy, "the paper" exists even though there is no single, unified paper. When people report on their inner experiences, Dennett considers their reports to be more like theorizing than like describing. These reports may be informative, he says, but a psychologist is not to take them at face value. Dennett describes several phenomena that show that perception is more limited and less reliable than we perceive it to be.

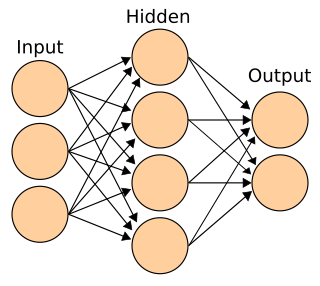

Connectionism is the name of an approach to the study of human mental processes and cognition that utilizes mathematical models known as connectionist networks or artificial neural networks. Connectionism has had many 'waves' since its beginnings.

The term autopoiesis refers to a system capable of producing and maintaining itself by creating its own parts. The term was introduced in the 1972 publication Autopoiesis and Cognition: The Realization of the Living by Chilean biologists Humberto Maturana and Francisco Varela to define the self-maintaining chemistry of living cells.

Jerry Alan Fodor was an American philosopher and the author of many crucial works in the fields of philosophy of mind and cognitive science. His writings in these fields laid the groundwork for the modularity of mind and the language of thought hypotheses, and he is recognized as having had "an enormous influence on virtually every portion of the philosophy of mind literature since 1960." At the time of his death in 2017, he held the position of State of New Jersey Professor of Philosophy, Emeritus, at Rutgers University, and had taught previously at the City University of New York Graduate Center and MIT.

Modularity of mind is the notion that a mind may, at least in part, be composed of innate neural structures or mental modules which have distinct, established, and evolutionarily developed functions. However, different definitions of "module" have been proposed by different authors. According to Jerry Fodor, the author of Modularity of Mind, a system can be considered 'modular' if its functions are made of multiple dimensions or units to some degree. One example of modularity in the mind is binding. When one perceives an object, they take in not only the features of an object, but the integrated features that can operate in sync or independently that create a whole. Instead of just seeing red, round, plastic, and moving, the subject may experience a rolling red ball. Binding may suggest that the mind is modular because it takes multiple cognitive processes to perceive one thing.

The language of thought hypothesis (LOTH), sometimes known as thought ordered mental expression (TOME), is a view in linguistics, philosophy of mind and cognitive science, forwarded by American philosopher Jerry Fodor. It describes the nature of thought as possessing "language-like" or compositional structure. On this view, simple concepts combine in systematic ways to build thoughts. In its most basic form, the theory states that thought, like language, has syntax.

In the philosophy of mind, the user illusion is a metaphor for a proposed description of consciousness that argues that conscious experience does not directly expose objective reality, but instead provides a simplified version of reality that allows humans to make decisions and act in their environment, akin to a computer desktop. According to this picture, our experience of the world is not immediate, as all sensation requires processing time. It follows that our conscious experience is less a perfect reflection of what is occurring, and more a simulation produced subconsciously by the brain. Therefore, there may be phenomena that exist beyond our peripheries, beyond what consciousness could create to isolate or reduce them.

The consciousness and binding problem is the problem of how objects, background, and abstract or emotional features are combined into a single experience. The binding problem refers to the overall encoding of our brain circuits for the combination of decisions, actions, and perception. It is considered a "problem" due to the fact that no complete model exists.

The intentional stance is a term coined by philosopher Daniel Dennett for the level of abstraction in which we view the behavior of an entity in terms of mental properties. It is part of a theory of mental content proposed by Dennett, which provides the underpinnings of his later works on free will, consciousness, folk psychology, and evolution.

Here is how it works: first you decide to treat the object whose behavior is to be predicted as a rational agent; then you figure out what beliefs that agent ought to have, given its place in the world and its purpose. Then you figure out what desires it ought to have, on the same considerations, and finally you predict that this rational agent will act to further its goals in the light of its beliefs. A little practical reasoning from the chosen set of beliefs and desires will in most instances yield a decision about what the agent ought to do; that is what you predict the agent will do.

What Is Life? The Physical Aspect of the Living Cell is a 1944 science book written for the lay reader by physicist Erwin Schrödinger. The book was based on a course of public lectures delivered by Schrödinger in February 1943, under the auspices of the Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies, where he was Director of Theoretical Physics, at Trinity College, Dublin. The lectures attracted an audience of about 400, who were warned "that the subject-matter was a difficult one and that the lectures could not be termed popular, even though the physicist’s most dreaded weapon, mathematical deduction, would hardly be utilized." Schrödinger's lecture focused on one important question: "how can the events in space and time which take place within the spatial boundary of a living organism be accounted for by physics and chemistry?"

In philosophy of mind, the computational theory of mind (CTM), also known as computationalism, is a family of views that hold that the human mind is an information processing system and that cognition and consciousness together are a form of computation. It is closely related to functionalism, a broader theory that defines mental states by what they do rather than what they're made of.

The philosophy of mind is a branch of philosophy that deals with the nature of the mind and its relation to the body and the external world.

Zenon Walter Pylyshyn was a Canadian cognitive scientist and philosopher. He was a Canada Council Senior Fellow from 1963 to 1964.

In philosophy of mind, qualia are defined as instances of subjective, conscious experience. The term qualia derives from the Latin neuter plural form (qualia) of the Latin adjective quālis meaning "of what sort" or "of what kind" in relation to a specific instance, such as "what it is like to taste a specific apple — this particular apple now".

Cognitive biology is an emerging science that regards natural cognition as a biological function. It is based on the theoretical assumption that every organism—whether a single cell or multicellular—is continually engaged in systematic acts of cognition coupled with intentional behaviors, i.e., a sensory-motor coupling. That is to say, if an organism can sense stimuli in its environment and respond accordingly, it is cognitive. Any explanation of how natural cognition may manifest in an organism is constrained by the biological conditions in which its genes survive from one generation to the next. And since by Darwinian theory the species of every organism is evolving from a common root, three further elements of cognitive biology are required: (i) the study of cognition in one species of organism is useful, through contrast and comparison, to the study of another species' cognitive abilities; (ii) it is useful to proceed from organisms with simpler to those with more complex cognitive systems, and (iii) the greater the number and variety of species studied in this regard, the more we understand the nature of cognition.

References

- ↑ Miller, George A. (1983), "Informavores", in Machlup, Fritz; Mansfield, Una (eds.), The Study of Information: Interdisciplinary Messages, Wiley-Interscience, pp. 111–113, ISBN 0-471-88717-X

- ↑ Schrödinger, Erwin (1944), What is Life?, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-42708-8

- ↑ Chevreau, Jonathan (1984-03-30), "Some A1 applications wishful thinking", The Globe and Mail

- ↑ Pylyshyn, Zenon (1984), Computation and Cognition: Toward a Foundation for Cognitive Science , MIT Press, ISBN 0-262-16098-6

- ↑ Dennett, Daniel (1997), Kinds of Minds: Towards an Understanding of Consciousness, Basic Books, ISBN 0-465-07351-4

- ↑ World Wide Words: Informavore , retrieved 2008-01-12