The Anomaluridae are a family of rodents found in central Africa. They are known as anomalures or scaly-tailed squirrels. The seven extant species are classified into three genera. Most are brightly coloured.

Draco volans, the common flying dragon, is a species of lizard endemic to Southeast Asia. Like other members of genus Draco, this species has the ability to glide using winglike lateral extensions of skin called patagia.

The flying mice, also known as the pygmy scaly-tails, pygmy scaly-tailed flying squirrels, or pygmy anomalures are not true mice, not true squirrels, and are not capable of true flight. These unusual rodents are essentially miniaturized versions of anomalures and are part of the same sub-Saharan African radiation of gliding mammal.

Scansoriopterygidae is an extinct family of climbing and gliding maniraptoran dinosaurs. Scansoriopterygids are known from five well-preserved fossils, representing four species, unearthed in the Tiaojishan Formation fossil beds of Liaoning and Hebei, China.

A number of animals have evolved aerial locomotion, either by powered flight or by gliding. Flying and gliding animals have evolved separately many times, without any single ancestor. Flight has evolved at least four times, in the insects, pterosaurs, birds, and bats. Gliding has evolved on many more occasions. Usually the development is to aid canopy animals in getting from tree to tree, although there are other possibilities. Gliding, in particular, has evolved among rainforest animals, especially in the rainforests in Asia where the trees are tall and widely spaced. Several species of aquatic animals, and a few amphibians and reptiles have also evolved to acquire this gliding flight ability, typically as a means of evading predators.

Sharovipteryx, is a genus of early gliding reptiles containing the single species Sharovipteryx mirabilis. It is known from a single fossil and is the only glider with a membrane surrounding the pelvis instead of the pectoral girdle. This lizard-like reptile was found in 1965 in the Madygen Formation, Dzailauchou, on the southwest edge of the Fergana valley in Kyrgyzstan, in what was then the Asian part of U.S.S.R. dating to the middle-late Triassic period. The Madygen horizon displays flora that put it in the Upper Triassic. An unusual reptile, Longisquama, was also found there.

The Philippine flying lemur or Philippine colugo, known locally as kagwang, is one of two species of colugo or "flying lemurs". It is monotypic of its genus. Although called a flying lemur, it cannot fly and is not a lemur. Instead, it glides as it leaps among trees.

Gliding flight is heavier-than-air flight without the use of thrust; the term volplaning also refers to this mode of flight in animals. It is employed by gliding animals and by aircraft such as gliders. This mode of flight involves flying a significant distance horizontally compared to its descent and therefore can be distinguished from a mostly straight downward descent like with a round parachute.

Mecistotrachelos is an extinct genus of gliding reptile believed to be an archosauromorph, distantly related to crocodylians and dinosaurs. The type and only known species is M. apeoros. This specific name translates to "soaring longest neck", in reference to its gliding habits and long neck. This superficially lizard-like animal was able to spread its lengthened ribs and glide on wing-like membranes. Mecistotrachelos had a much longer neck than other gliding reptiles of the Triassic such as Icarosaurus and Kuehneosaurus. It was probably an arboreal insectivore.

Pel's flying squirrel or Pel's scaly-tailed squirrel is a species of rodent in the family Anomaluridae. It is found in Liberia, Ivory Coast, and Ghana, where it lives in lowland tropical rainforests.

The red and white giant flying squirrel is a species of rodent in the family Sciuridae. It is the largest species of giant squirrel and has blue eyes. It is also known as the Chinese giant flying squirrel. At over a meter long including its tail, the red and white giant flying squirrel is the largest of its kind. Endemic to central and southern China and Taiwan, they inhabit dense hillside forests in mountainous terrain. They spend their days sleeping, emerging after sundown to forage in the trees. Their diet consists primarily of nuts and fruits, but also includes leafy vegetation as well as some insects and their larvae. Red and white giants move between trees by gliding, typically over distances of about 10–20 meters. This squirrel has a wide range and is relatively common, and the International Union for Conservation of Nature lists it as being of "least concern".

The Cameroon scaly-tail, also referred to as the Cameroon anomalure, flightless anomalure, or flightless scaly-tail, is a rodent species endemic to West Central Africa. The scientific literature has never reported observations of live individuals. The taxonomic classification of the species has been subject to recent revision.

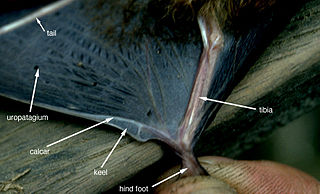

Macrotus is a genus of bats in the Neotropical family Phyllostomidae. This genus contains two species, Macrotus californicus commonly known as California leaf-nosed bat and Macrotus waterhousii commonly known as Mexican or Waterhouse's leaf-nosed bat. The range of this family includes the warmer parts of the southwestern United States, Mexico, Central and South America, and the Bahama Islands. Characteristic for the genus are large ears and the name giving triangular skin flap above the nose, the "leaf". The California Leaf-nosed Bat inhabits the arid deserts of the southwestern United States as far north as Nevada, south to Baja California and Sonora, Mexico. The California Leaf-nosed Bat is of medium size, with a total length between 9 and 11 cm Its most distinctive features are the large ears, connected across the forehead. The body is pale grayish brown dorsally with whitish under parts. The pelage (fur) on the body is silky, the hairs on the back about 8 mm, on the front about 6 mm long. The posterior base of the ears are covered with hair of a woolly texture while the interior surface and most of the anterior border shows scattered long hairs. The flight membranes are thin and delicate; the wings are broad and the tail is slightly shorter that the long hind limbs and extends several millimeters beyond the uropatagium. Macrotus waterhousii is also a big eared Bat which has ranges from Sonora to Hidalgo Mexico, south to Guatemala and the Greater Antilles and Bahamas. This species roosts primarily in caves, but also in mines and buildings. This species is also insectivorous, primarily consuming insects of the order Lepidoptera and Orthoptera. The mating and parturition times of M. waterhousii vary from island to island with 4–5 months gestation.

Role of skin in locomotion describes how the integumentary system is involved in locomotion. Typically the integumentary system can be thought of as skin, however the integumentary system also includes the segmented exoskeleton in arthropods and feathers of birds. The primary role of the integumentary system is to provide protection for the body. However, the structure of the skin has evolved to aid animals in their different modes of locomotion. Soft bodied animals such as starfish rely on the arrangement of the fibers in their tube feet for movement. Eels, snakes, and fish use their skin like an external tendon to generate the propulsive forces need for undulatory locomotion. Vertebrates that fly, glide, and parachute also have a characteristic fiber arrangements of their flight membranes that allows for the skin to maintain its structural integrity during the stress and strain experienced during flight.

Yi is a genus of scansoriopterygid dinosaurs from the Late Jurassic of China. Its only species, Yi qi, is known from a single fossil specimen of an adult individual found in Middle or Late Jurassic Tiaojishan Formation of Hebei, China, approximately 160 million years ago. It was a small, possibly tree-dwelling (arboreal) animal. Like other scansoriopterygids, Yi possessed an unusual, elongated third finger, that appears to have helped to support a membranous gliding plane made of skin. The planes of Yi qi were also supported by a long, bony strut attached to the wrist. This modified wrist bone and membrane-based plane is unique among all known dinosaurs, and might have resulted in wings similar in appearance to those of bats.

Ambopteryx is a genus of scansoriopterygid dinosaur from the Oxfordian stage of the Late Jurassic of China. It is the second dinosaur to be found with both feathers and bat-like membranous wings. Yi, the first such dinosaur, was described in 2015 and is the sister taxon to Ambopteryx. The holotype specimen is thought to be a sub-adult or adult. The specimen is estimated to have had a body length of 32 centimetres (13 in) and a weight of 306 grams (0.675 lb). The genus includes one species, Ambopteryx longibrachium.