In atomic physics, the Bohr model or Rutherford–Bohr model of the atom, presented by Niels Bohr and Ernest Rutherford in 1913, consists of a small, dense nucleus surrounded by orbiting electrons. It is analogous to the structure of the Solar System, but with attraction provided by electrostatic force rather than gravity, and with the electron energies quantized.

Atomic, molecular, and optical physics (AMO) is the study of matter–matter and light–matter interactions, at the scale of one or a few atoms and energy scales around several electron volts. The three areas are closely interrelated. AMO theory includes classical, semi-classical and quantum treatments. Typically, the theory and applications of emission, absorption, scattering of electromagnetic radiation (light) from excited atoms and molecules, analysis of spectroscopy, generation of lasers and masers, and the optical properties of matter in general, fall into these categories.

In atomic physics and quantum chemistry, the electron configuration is the distribution of electrons of an atom or molecule in atomic or molecular orbitals. For example, the electron configuration of the neon atom is 1s2 2s2 2p6, meaning that the 1s, 2s and 2p subshells are occupied by 2, 2 and 6 electrons respectively.

An extended periodic table theorises about chemical elements beyond those currently known in the periodic table and proven. The element with the highest atomic number known is oganesson (Z = 118), which completes the seventh period (row) in the periodic table. All elements in the eighth period and beyond thus remain purely hypothetical.

Electron capture is a process in which the proton-rich nucleus of an electrically neutral atom absorbs an inner atomic electron, usually from the K or L electron shells. This process thereby changes a nuclear proton to a neutron and simultaneously causes the emission of an electron neutrino.

A nuclear isomer is a metastable state of an atomic nucleus, in which one or more nucleons (protons or neutrons) occupy excited state (higher energy) levels. "Metastable" describes nuclei whose excited states have half-lives 100 to 1000 times longer than the half-lives of the excited nuclear states that decay with a "prompt" half life (ordinarily on the order of 10−12 seconds). The term "metastable" is usually restricted to isomers with half-lives of 10−9 seconds or longer. Some references recommend 5 × 10−9 seconds to distinguish the metastable half life from the normal "prompt" gamma-emission half-life. Occasionally the half-lives are far longer than this and can last minutes, hours, or years. For example, the 180m

73Ta

nuclear isomer survives so long (at least 1015 years) that it has never been observed to decay spontaneously. The half-life of a nuclear isomer can even exceed that of the ground state of the same nuclide, as shown by 180m

73Ta

as well as 192m2

77Ir

, 210m

83Bi

, 242m

95Am

and multiple holmium isomers.

The emission spectrum of a chemical element or chemical compound is the spectrum of frequencies of electromagnetic radiation emitted due to electrons making a transition from a high energy state to a lower energy state. The photon energy of the emitted photons is equal to the energy difference between the two states. There are many possible electron transitions for each atom, and each transition has a specific energy difference. This collection of different transitions, leading to different radiated wavelengths, make up an emission spectrum. Each element's emission spectrum is unique. Therefore, spectroscopy can be used to identify elements in matter of unknown composition. Similarly, the emission spectra of molecules can be used in chemical analysis of substances.

A scintillator is a material that exhibits scintillation, the property of luminescence, when excited by ionizing radiation. Luminescent materials, when struck by an incoming particle, absorb its energy and scintillate. Sometimes, the excited state is metastable, so the relaxation back down from the excited state to lower states is delayed. The process then corresponds to one of two phenomena: delayed fluorescence or phosphorescence. The correspondence depends on the type of transition and hence the wavelength of the emitted optical photon.

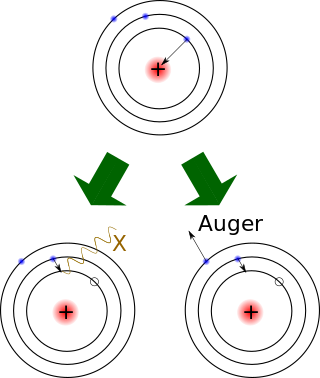

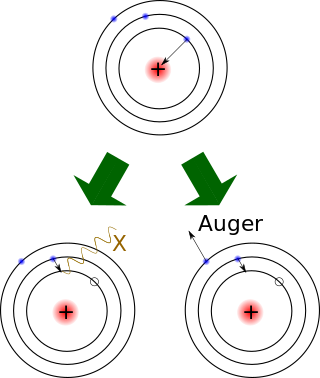

Internal conversion is an atomic decay process where an excited nucleus interacts electromagnetically with one of the orbital electrons of an atom. This causes the electron to be emitted (ejected) from the atom. Thus, in internal conversion, a high-energy electron is emitted from the excited atom, but not from the nucleus. For this reason, the high-speed electrons resulting from internal conversion are not called beta particles, since the latter come from beta decay, where they are newly created in the nuclear decay process.

In condensed matter physics, scintillation is the physical process where a material, called a scintillator, emits ultraviolet or visible light under excitation from high energy photons or energetic particles. See scintillator and scintillation counter for practical applications.

Double electron capture is a decay mode of an atomic nucleus. For a nuclide (A, Z) with a number of nucleons A and atomic number Z, double electron capture is only possible if the mass of the nuclide (A, Z−2) is lower.

Koopmans' theorem states that in closed-shell Hartree–Fock theory (HF), the first ionization energy of a molecular system is equal to the negative of the orbital energy of the highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO). This theorem is named after Tjalling Koopmans, who published this result in 1934.

Iodine-123 (123I) is a radioactive isotope of iodine used in nuclear medicine imaging, including single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) or SPECT/CT exams. The isotope's half-life is 13.2230 hours; the decay by electron capture to tellurium-123 emits gamma radiation with a predominant energy of 159 keV. In medical applications, the radiation is detected by a gamma camera. The isotope is typically applied as iodide-123, the anionic form.

Rydberg matter is an exotic phase of matter formed by Rydberg atoms; it was predicted around 1980 by É. A. Manykin, M. I. Ozhovan and P. P. Poluéktov. It has been formed from various elements like caesium, potassium, hydrogen and nitrogen; studies have been conducted on theoretical possibilities like sodium, beryllium, magnesium and calcium. It has been suggested to be a material that diffuse interstellar bands may arise from. Circular Rydberg states, where the outermost electron is found in a planar circular orbit, are the most long-lived, with lifetimes of up to several hours, and are the most common.

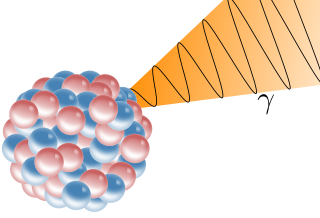

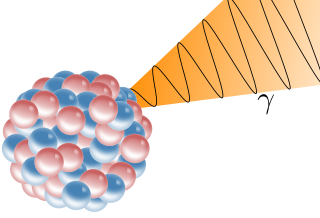

A gamma ray, also known as gamma radiation (symbol γ or ), is a penetrating form of electromagnetic radiation arising from the radioactive decay of atomic nuclei. It consists of the shortest wavelength electromagnetic waves, typically shorter than those of X-rays. With frequencies above 30 exahertz (3×1019 Hz), it imparts the highest photon energy. Paul Villard, a French chemist and physicist, discovered gamma radiation in 1900 while studying radiation emitted by radium. In 1903, Ernest Rutherford named this radiation gamma rays based on their relatively strong penetration of matter; in 1900 he had already named two less penetrating types of decay radiation (discovered by Henri Becquerel) alpha rays and beta rays in ascending order of penetrating power.

Nuclear resonance fluorescence (NRF) is a nuclear process in which a nucleus absorbs and emits high-energy photons called gamma rays. NRF interactions typically take place above 1 MeV, and most NRF experiments target heavy nuclei such as uranium and thorium

Total absorption spectroscopy is a measurement technique that allows the measurement of the gamma radiation emitted in the different nuclear gamma transitions that may take place in the daughter nucleus after its unstable parent has decayed by means of the beta decay process. This technique can be used for beta decay studies related to beta feeding measurements within the full decay energy window for nuclei far from stability.

Conversion electron Mössbauer spectroscopy (CEMS) is a Mössbauer spectroscopy technique based on conversion electron.

The index of physics articles is split into multiple pages due to its size.

Helmut Paul was an Austrian nuclear and atomic physicist. He taught as a full professor of experimental physics at the University of Linz from 1971 to 1996. Since then he was professor emeritus. He was Rector of the University from 1974 to 1977.