Wrought iron is an iron alloy with a very low carbon content in contrast to that of cast iron. It is a semi-fused mass of iron with fibrous slag inclusions, which give it a wood-like "grain" that is visible when it is etched, rusted, or bent to failure. Wrought iron is tough, malleable, ductile, corrosion resistant, and easily forge welded, but is more difficult to weld electrically.

Ashdown Forest is an ancient area of open heathland occupying the highest sandy ridge-top of the High Weald Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty. It is situated some 30 miles (48 km) south of London in the county of East Sussex, England. Rising to an elevation of 732 feet (223 m) above sea level, its heights provide expansive vistas across the heavily wooded hills of the Weald to the chalk escarpments of the North Downs and South Downs on the horizon.

The Weald is an area of South East England between the parallel chalk escarpments of the North and the South Downs. It crosses the counties of Hampshire, Surrey, West Sussex, East Sussex, and Kent. It has three parts, the sandstone "High Weald" in the centre, the clay "Low Weald" periphery and the Greensand Ridge, which stretches around the north and west of the Weald and includes its highest points. The Weald once was covered with forest and its name, Old English in origin, signifies "woodland". The term is still used, as scattered farms and villages sometimes refer to the Weald in their names.

A blast furnace is a type of metallurgical furnace used for smelting to produce industrial metals, generally pig iron, but also others such as lead or copper. Blast refers to the combustion air being supplied above atmospheric pressure.

Pease Pottage is a village in the Mid Sussex District of West Sussex, England. It lies on the southern edge of the Crawley built-up area, in the civil parish of Slaugham.

Hartfield is a village and civil parish in the Wealden district of East Sussex, England. The parish also includes the settlements of Colemans Hatch, Hammerwood and Holtye, all lying on the northern edge of Ashdown Forest.

The Wealden iron industry was located in the Weald of south-eastern England. It was formerly an important industry, producing a large proportion of the bar iron made in England in the 16th century and most British cannon until about 1770. Ironmaking in the Weald used ironstone from various clay beds, and was fuelled by charcoal made from trees in the heavily wooded landscape. The industry in the Weald declined when ironmaking began to be fuelled by coke made from coal, which does not occur accessibly in the area.

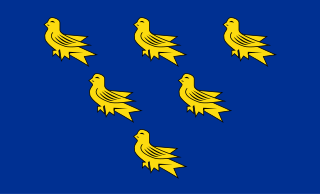

Sussex, from the Old English 'Sūþsēaxe', is a historic county in South East England.

Maresfield is a village and civil parish in the Wealden District of East Sussex, England. The village itself lies 1.5 miles (2.4 km) north from Uckfield; the nearby villages of Nutley and Fairwarp; and the smaller settlements of Duddleswell and Horney Common; and parts of Ashdown Forest all lie within Maresfield parish.

A bloomery is a type of metallurgical furnace once used widely for smelting iron from its oxides. The bloomery was the earliest form of smelter capable of smelting iron. Bloomeries produce a porous mass of iron and slag called a bloom. The mix of slag and iron in the bloom, termed sponge iron, is usually consolidated and further forged into wrought iron. Blast furnaces, which produce pig iron, have largely superseded bloomeries.

Buxted is a village and civil parish in the Wealden district of East Sussex in England. The parish is situated on the Weald, north of Uckfield; the settlements of Five Ash Down, Heron's Ghyll and High Hurstwood are included within its boundaries. At one time its importance lay in the Wealden iron industry, and later it became commercially important in the poultry and egg industry.

The Classis Britannica was a provincial naval fleet of the navy of ancient Rome. Its purpose was to control the English Channel and the waters around the Roman province of Britannia. Unlike modern "fighting navies", its job was largely the logistical movement of personnel and support, and keeping open communication routes across the Channel.

Nutley is a village in the Wealden District of East Sussex, England. It lies about 5 mi (8.0 km) north-west of Uckfield, the main road being the A22. Nutley, Fairwarp and Maresfield together form the Maresfield civil parish.

Tilgate Park is a large recreational park situated south of Tilgate, South-East Crawley.

William Levett was an English clergyman. An Oxford-educated country rector, he was a pivotal figure in the use of the blast furnace to manufacture iron. With the patronage of the English Crown, furnaces in Sussex under Levett's ownership cast the first iron muzzle-loader cannons in England in 1543, a development which enabled England to ultimately reconfigure the global balance-of-power by becoming an ascendant naval force. William Levett continued to perform his ministerial duties while building an early munitions empire, and left the riches he accumulated to a wide variety of charities at his death.

The Medway and its tributaries and sub-tributaries have been used for over 1,150 years as a source of power. There are over two hundred sites where the use of water power is known. These uses included corn milling, fulling, paper making, iron smelting, pumping water, making gunpowder, vegetable oil extraction, and electricity generation. Today, there is just one watermill working for trade. Those that remain have mostly been converted. Such conversions include a garage, dwellings, restaurants, museums and a wedding venue. Some watermills are mere derelict shells, lower walls or lesser remains. Of the majority, there is nothing to be seen. A large number of tributaries feed into the River Medway. The tributaries that powered watermills will be described in the order that they feed in. The mills are described in order from source to mouth. Left bank and right bank are referred to as though the reader is facing downstream. This article covers the tributaries that feed in above Penshurst.

Metals and metal working had been known to the people of modern Italy since the Bronze Age. By 53 BC, Rome had expanded to control an immense expanse of the Mediterranean. This included Italy and its islands, Spain, Macedonia, Africa, Asia Minor, Syria and Greece; by the end of the Emperor Trajan's reign, the Roman Empire had grown further to encompass parts of Britain, Egypt, all of modern Germany west of the Rhine, Dacia, Noricum, Judea, Armenia, Illyria, and Thrace. As the empire grew, so did its need for metals.

St Leonard's Forest is at the western end of the Wealden Forest Ridge which runs from Horsham to Tonbridge, and is part of the High Weald Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty. It lies on the ridge to the south of the A264 between Horsham and Crawley with the villages of Colgate and Lower Beeding within it. The A24 lies to west and A23 to the East and A272 through Cowfold to the south. Much has been cleared, but a large area is still wooded. Forestry England has 289 ha. which is open to the public, as are Owlbeech and Leechpool Woods to the east of Horsham, and Buchan Country Park to the SW of Crawley. The rest is private with just a few public footpaths and bridleways. Leonardslee Gardens were open to the public until July 2010 and re-opened in April 2019. An area of 85.4 hectares is St Leonards Forest Site of Special Scientific Interest.

Ashdown Forest contains a wealth of archeological features. Absence of ploughing, predominance of heathland and lack of building development have allowed archaeological sites to survive and remain visible. More than 570 such sites have been identified, including Bronze Age round barrows, Iron Age enclosures, prehistoric field systems, iron workings from Roman times onwards, the Pale, medieval and post-medieval pillow mounds for the rearing of rabbits, and a set of military kitchen mounds between Camp Hill and Nutley dating from 1793 that are among the only surviving ones in the United Kingdom. The earliest known trace of human activity in Ashdown Forest is a stone hand axe found near Gills Lap, which is thought to be about 50,000 years old. The vast majority of finds however date from the Mesolithic and onwards into the modern era.

Ashdown Forest, a former royal hunting forest situated some 30 miles south-east of London, is a large area of lowland heathland whose ecological importance has been recognised by its designation as a UK Site of Special Scientific Interest and by the European Union as a Special Protection Area for birds and a Special Area of Conservation for its heathland habitats, and by its membership of Natura 2000, which brings together Europe's most important and threatened wildlife areas.