Related Research Articles

Comer Vann Woodward was an American historian who focused primarily on the American South and race relations. He was long a supporter of the approach of Charles A. Beard, stressing the influence of unseen economic motivations in politics.

The history of Atlanta dates back to 1836, when Georgia decided to build a railroad to the U.S. Midwest and a location was chosen to be the line's terminus. The stake marking the founding of "Terminus" was driven into the ground in 1837. In 1839, homes and a store were built there and the settlement grew. Between 1845 and 1854, rail lines arrived from four different directions, and the rapidly growing town quickly became the rail hub for the entire Southern United States. During the American Civil War, Atlanta, as a distribution hub, became the target of a major Union campaign, and in 1864, Union William Sherman's troops set on fire and destroyed the city's assets and buildings, save churches and hospitals. After the war, the population grew rapidly, as did manufacturing, while the city retained its role as a rail hub. Coca-Cola was launched here in 1886 and grew into an Atlanta-based world empire. Electric streetcars arrived in 1889, and the city added new "streetcar suburbs".

The Cotton States and International Exposition was a world's fair held in Atlanta, Georgia, United States in 1895. The exposition was designed "to foster trade between southern states and South American nations as well as to show the products and facilities of the region to the rest of the nation and Europe."

The Dunning School was a historiographical school of thought regarding the Reconstruction period of American history (1865–1877), supporting conservative elements against the Radical Republicans who introduced civil rights in the South. It was named for Columbia University professor William Archibald Dunning, who taught many of its followers.

Charles Henry Smith was an American writer and politician from the state of Georgia. He used the pen name Bill Arp for nearly 40 years. He had a national reputation as a homespun humorist during his lifetime, and at least four communities are named for him.

The 1906 Atlanta Race Massacre, also known as the 1906 Atlanta Race Riot, was an episode of mass racial violence against African Americans in the United States in September 1906. Violent attacks by armed mobs of White Americans against African Americans in Atlanta, Georgia, began after newspapers, on the evening of September 22, 1906, published several unsubstantiated and luridly detailed reports of the alleged rapes of 4 local women by black men. The violence lasted through September 24, 1906. The events were reported by newspapers around the world, including the French Le Petit Journal which described the "lynchings in the USA" and the "massacre of Negroes in Atlanta," the Scottish Aberdeen Press & Journal under the headline "Race Riots in Georgia," and the London Evening Standard under the headlines "Anti-Negro Riots" and "Outrages in Georgia." The final death toll of the conflict is unknown and disputed, but officially at least 25 African Americans and two whites died. Unofficial reports ranged from 10–100 black Americans killed during the massacre. According to the Atlanta History Center, some black Americans were hanged from lampposts; others were shot, beaten or stabbed to death. They were pulled from street cars and attacked on the street; white mobs invaded black neighborhoods, destroying homes and businesses.

The Commission on Interracial Cooperation (1918–1944) was an organization founded in Atlanta, Georgia, December 18, 1918, and officially incorporated in 1929. Will W. Alexander, pastor of a local white Methodist church, was head of the organization. It was formed in the aftermath of violent race riots that occurred in 1917 in several southern cities. In 1944, it merged with the Southern Regional Council.

This is a selected bibliography of the main scholarly books and articles of Reconstruction, the period after the American Civil War, 1863–1877.

Charles Colcock Jones Jr. was a politician, attorney and author from Georgia, United States. He was the mayor of Savannah, Georgia, immediately prior to Sherman's March to the Sea.

The Southern Regional Council (SRC) is a reform-oriented organization created in 1944 to avoid racial violence and promote racial equality in the Southern United States. Voter registration and political-awareness campaigns are used toward this end. The SRC evolved in 1944 from the Commission on Interracial Cooperation. It is headquartered in Atlanta, Georgia.

The civil rights movement (1865–1896) aimed to eliminate racial discrimination against African Americans, improve their educational and employment opportunities, and establish their electoral power, just after the abolition of slavery in the United States. The period from 1865 to 1895 saw a tremendous change in the fortunes of the Black community following the elimination of slavery in the South.

The Lily-White Movement was an anti-black political movement within the Republican Party in the United States in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. It was a response to the political and socioeconomic gains made by African-Americans following the Civil War and the Thirteenth Amendment to the Constitution, which eliminated slavery and involuntary servitude.

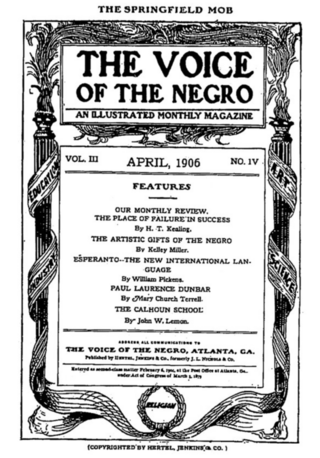

The Voice of the Negro was a literary periodical aimed at a national audience of African Americans which was published from 1904 to 1907. It was created in Atlanta, Georgia in June 1904 by Austin N. Jenkins, the white manager of the publishing company J. L. Nichols and Company. He gave full control of the magazine to the Black editors John W. E. Bowen, Sr. and Jesse Max Barber.

Poor White is a sociocultural classification used to describe economically disadvantaged Whites in the English-speaking world, especially White Americans with low incomes.

The following is a timeline of the history of the city of Atlanta, Georgia, United States.

Charles Henry James Taylor (1857–1899), was an American journalist, editor, lawyer, orator, and political organizer. An early supporter of Democratic President Grover Cleveland, he was appointed Minister to Liberia during Cleveland's first presidential term.

The Southern Cultivator is a defunct agrarian publication that was published in the Southern United States.

Francis Fontaine was an American Confederate soldier, plantation owner, newspaper editor, poet and novelist from the state of Georgia.

The black-and-tan faction was an American biracial faction in the Republican Party in the South from the 1870s to the 1960s. It replaced the Negro Republican Party faction's name after the 1890s.

The Georgia Railroad strike of 1909, also known as the Georgia race strike, was a labor strike that involved white firemen working for the Georgia Railroad that lasted from May 17 to May 29. White firemen, organized under the Brotherhood of Locomotive Firemen and Enginemen, resented the hiring of African American firemen by the railroad and accompanying policies regarding seniority. The labor dispute ended in Federal mediation under the terms of the Erdman Act, with the mediators deciding in favor of the railroad on all major issues.

References

- ↑ Internet archives

- 1 2 David B. Parker, Alias Bill Arp: Charles Henry Smith and the South's Goodly Heritage, Athens, Georgia: University of Georgia Press, 2009, pp. 94-95

- ↑ Open Library: Psyche

- ↑ Open Library: Journal of the Constitutional convention of the people of Georgia

- ↑ Open Library: Catalogue of Ores, Rocks and Woods

- ↑ Open Library: Democracy Examined

- ↑ Open Library: The Commonwealth of Georgia

- ↑ Open Library: The life and services of ex-Governor Charles Jones Jenkins

- ↑ Open Library: Catalogue of the Young Men's Library of Atlanta

- ↑ Open Library: Political and Judicial Divisions of the Commonwealth of Georgia

- ↑ Open Library: The Negro Problem

- ↑ Open Library: The Education of the Negro

- ↑ Open Library: Whites and blacks

- ↑ Open Library: Amanda, the Octoroon

- ↑ Open Library: The Discipline of Dancing