Related Research Articles

A mummy is a dead human or an animal whose soft tissues and organs have been preserved by either intentional or accidental exposure to chemicals, extreme cold, very low humidity, or lack of air, so that the recovered body does not decay further if kept in cool and dry conditions. Some authorities restrict the use of the term to bodies deliberately embalmed with chemicals, but the use of the word to cover accidentally desiccated bodies goes back to at least the early 17th century.

Saqqara, also spelled Sakkara or Saccara in English, is an Egyptian village in the markaz (county) of Badrashin in the Giza Governorate, that contains ancient burial grounds of Egyptian royalty, serving as the necropolis for the ancient Egyptian capital, Memphis. Saqqara contains numerous pyramids, including the Pyramid of Djoser, sometimes referred to as the Step Tomb, and a number of mastaba tombs. Located some 30 km (19 mi) south of modern-day Cairo, Saqqara covers an area of around 7 by 1.5 km.

Nekhen, also known as Hierakonpolis was the religious and political capital of Upper Egypt at the end of prehistoric Egypt and probably also during the Early Dynastic Period.

Djer is considered the third pharaoh of the First Dynasty of ancient Egypt in current Egyptology. He lived around the mid 31st century BC and reigned for c. 40 years. A mummified forearm of Djer or his wife was discovered by Egyptologist Flinders Petrie, but was discarded by Émile Brugsch.

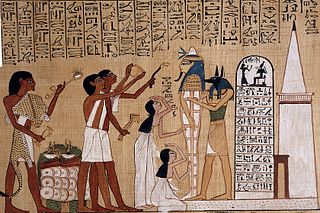

The ancient Egyptians had an elaborate set of funerary practices that they believed were necessary to ensure their immortality after death. These rituals included mummifying the body, casting magic spells, and burials with specific grave goods thought to be needed in the afterlife.

Tomb KV60 is an ancient Egyptian tomb in the Valley of the Kings, Egypt. It was discovered by Howard Carter in 1903, and re-excavated by Donald P. Ryan in 1989. It is one of the more perplexing tombs of the Theban Necropolis, due to the uncertainty over the identity of one female mummy found there (KV60A). She is identified by some, such as Egyptologist Elizabeth Thomas, to be that of the Eighteenth Dynasty pharaoh Hatshepsut; this identification is advocated for by Zahi Hawass.

In ancient Egypt, cats were represented in social and religious scenes dating as early as 1980 BC. Several ancient Egyptian deities were depicted and sculptured with cat-like heads such as Mafdet, Bastet and Sekhmet, representing justice, fertility, and power, respectively. The deity Mut was also depicted as a cat and in the company of a cat.

Hetepheres I was a queen of Egypt during the Fourth Dynasty of Egypt who was a wife of one king, the mother of the next king, the grandmother of two more kings, and the figure who tied together two dynasties.

This is a glossary of ancient Egypt artifacts.

The Gebelein predynastic mummies are six naturally mummified bodies, dating to approximately 3400 BC from the Late Predynastic period of Ancient Egypt. They were the first complete predynastic bodies to be discovered. The well-preserved bodies were excavated at the end of the nineteenth century by Wallis Budge, the British Museum Keeper for Egyptology, from shallow sand graves near Gebelein in the Egyptian desert.

Nefer-Setekh is the name of an ancient Egyptian high official, who lived and worked either during the late midst of the 2nd or during the beginning of the 3rd dynasty. He became known by his name, which was addressed to the deity Seth.

The Department of Egyptian Antiquities of the Louvre is a department of the Louvre that is responsible for artifacts from the Nile civilizations which date from 4,000 BC to the 4th century. The collection, comprising over 50,000 pieces, is among the world's largest, overviews Egyptian life spanning Ancient Egypt, the Middle Kingdom, the New Kingdom, Coptic art, and the Roman, Ptolemaic, and Byzantine periods.

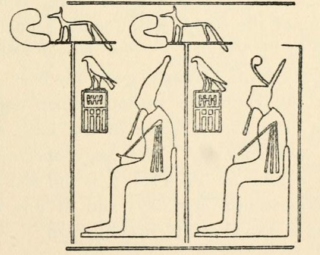

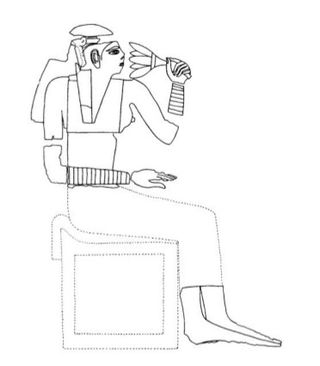

Nisuheqet was an ancient Egyptian king's son of the Second Dynasty. Nisuheqet is only known from his stela found in tomb 964.H.8 at Helwan. The only title he bears on this monument is king's son. The stela is made of limestone and shows the prince on the left, sitting on a chair with an offering table and offerings in front of him. The stela was discovered in excavations by Zaki Saad at Helwan, that were conducted between 1952 and 1954. The royal father of this king's son remains unknown.

Khenmetptah was an ancient Egyptian king's daughter who lived most likely in the Second Dynasty. She is only known from her stela once placed in her tomb and found at Helwan. On the stela Khenmetptah is shown sitting on a chair in front of an offering table. Next to the offering table are shown many offerings. Above this scene is a short text: the king's daughter Khenmetptah. Her royal father is not known. On stylistical grounds the stela is datable to the Second Dynasty.

Satkhnum was an ancient Egyptian king's daughter who lived most likely in the Second Dynasty. She is only known from her stela once placed in her tomb and found at Helwan. On the stela Satkhnum is shown sitting on a chair in front of an offering table. Next to the offering table are shown many offerings. Above this scene is a short text: Satkhnum, the king's daughter. Her royal father is not known. On stylistical grounds the stela is datable to the Second Dynasty.

At Helwan south of modern Cairo was excavated a large ancient Egyptian cemetery with more than 10,000 burials. The cemetery was in use from the Naqada Period around 3200 BC to the Fourth Dynasty and again at the beginning of the Middle Kingdom and then up to the Roman Period and beyond. The burial ground was discovered and excavated by Zaki Saad in 1942 to 1954. Further excavations started in 1997 by an Australian expedition. The excavations of Zaki Saad were never fully published, only several preliminary reports appeared. Helwan was most likely the cemetery of Memphis in the first Dynasties. The tombs range from small pits to bigger elaborated mastabas. Regarding the underground parts of these tombs, two types are attested. There are on one side pits with the burial at the bottom and there are on the other side underground chambers, reached via a pit or via a staircase. The majority of burials are for one deceased.

Meriiti was an ancient Egyptian official living at the end of the First Dynasty around 2900 BC. He is only known from his stela found in tomb 810.H.11 at Helwan. The stela was found in the burial chamber next to the coffin. It shows on the left Meriiti sitting on a chair with offerings in front of him. On the right side of the stela is a list of Meriiti's titles.

The archaeology of Ancient Egypt is the study of the archaeology of Egypt, stretching from prehistory through three millennia of documented history. Egyptian archaeology is one of the branches of Egyptology.

Henut-wedjebu was an ancient Egyptian noblewoman buried in the late Eighteenth Dynasty during the reigns of Amenhotep III or Amenhotep IV. She is known from her intact burial at Sheikh Abd el-Qurna, discovered in 1896 by French Egyptologist Georges Daressy. The same year, Henut-wedjebu's coffin and mummy was purchased by Charles Parsons and gifted to Washington University in St. Louis. Her coffin is on display in the Saint Louis Art Museum.

The Qurna Queen was an ancient Egyptian woman who lived in the Seventeenth Dynasty of Egypt, around 1600 BC to 1500 BC, whose mummy is now in the National Museum of Scotland. She was in her late teens or early twenties at the time of her death, and her mummy and coffin were found in El-Kohr, near the Valley of the Kings. Damage to her coffin means that her name has been lost. The quality of the grave goods and the location of the burial have been used to argue that the inhabitant of the grave was a member of the royal family. If this is the case, it would mean that the site's mummies, coffins and grave goods would make up the only complete royal burial exported from Egypt in its entirety.

References

- ↑ "Calling Dr Jones". This Week At Macquarie University. 14 September 2015. Retrieved 5 February 2024.

- ↑ E. Christiana Köhler, Jana Jones: Helwan II, The Early Dynastic and Old Kingdom Funerary Relief Slabs, Studien zur Archäologie und Geschichte Altägyptens, Band 25, Rahden 2009, ISBN 978-3-86757-971-1, p. 1

- ↑ Friedman, Renée Frances; Watrall, Ethan; Jones, Jana; Fahmy, Ahmed G.; Van Neer, Wim; Linseele, Veerle (2002). "Excavations at Hierakonpolis". Archéo-Nil. 12 (1): 55–68. doi:10.3406/arnil.2002.870 . Retrieved 17 August 2024.

- ↑ Jones, Jana (28 September 2018). "Prehistoric Egyptians mummified bodies 1,500 years before the pharaohs". CNN. Retrieved 5 February 2024.

- ↑ Wei-Haas, Maya (15 August 2018). "Mummy Helps Confirm Earliest Egyptian Embalming Recipe". National Geographic. Retrieved 5 February 2024.

- ↑ Masterson, Andrew (15 August 2018). "Egyptian mummification pushed back 1500 years". cosmosmagazine.com. Retrieved 5 February 2024.

- ↑ McGrath, Ciaran (16 August 2018). "Egyptians were making mummies more than 5,000 years ago". Express.co.uk. Retrieved 17 August 2024.