Dorothy Coade Hewett was an Australian playwright, poet and author. She wrote in a number of different literary styles: modernism, socialist realism, expressionism and avant garde. She was a member of the Australian Communist Party in the 1950s and 1960s, which informed her work during that period.

Hal Gibson Pateshall Colebatch was a West Australian author, historian, poet, lecturer, journalist, editor, and lawyer.

A real-estate bubble or property bubble is a type of economic bubble that occurs periodically in local or global real estate markets, and it typically follows a land boom. A land boom is a rapid increase in the market price of real property such as housing until they reach unsustainable levels and then declines. This period, during the run-up to the crash, is also known as froth. The questions of whether real estate bubbles can be identified and prevented, and whether they have broader macroeconomic significance, are answered differently by schools of economic thought, as detailed below.

Poverty in Australia refers to the incidence of relative poverty in Australia and its measurement. Relative income poverty is measured as the percentage of the population that earns less than the median wage of the working population.

Affordable housing is housing which is deemed affordable to those with a household income at or below the median, as rated by the national government or a local government by a recognized housing affordability index. Most of the literature on affordable housing refers to mortgages and a number of forms that exist along a continuum – from emergency homeless shelters, to transitional housing, to non-market rental, to formal and informal rental, indigenous housing, and ending with affordable home ownership. Demand for affordable housing is generally associated with a decrease in housing affordability, such as rent increases, in addition to increased homelessness.

The Australian Dream or Great Australian Dream is, in its narrowest sense, a belief that in Australia, home ownership can lead to a better life and is an expression of success and security. The term is derived from the American Dream, which describes a similar phenomenon in the United States also starting in the 1940s, although they are differentiated from each other in that the American Dream is more concerned with the abstract notion that upward social mobility in general is achievable for all while the Australian Dream is more invested specifically in home ownership as a means of prosperity. Although this standard of living is enjoyed by many in the existing Australian population, commentators have argued that rising real house prices have made it increasingly difficult to achieve the "Great Australian Dream", especially for those living in large cities and the Millennials.

Tom Flood is an Australian novelist, playwright, and writer of short stories. His is best known for authoring the novel Oceana Fine for which he won several of Australia's top literary prizes; among them the Australian/Vogel Literary Award, the Miles Franklin Award, and the Victorian Premier's Literary Award.

Kate Lilley is a contemporary Australian poet and academic.

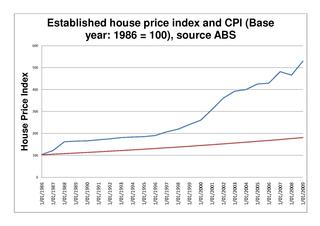

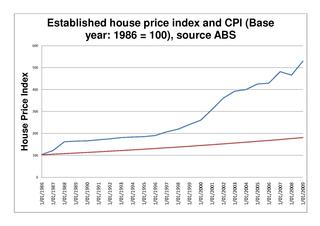

The Australian property market comprises the trade of land and its permanent fixtures located within Australia. The average Australian property price grew 0.5% per year from 1890 to 1990 after inflation, however rose from 1990 to 2017 at a faster rate. House prices in Australia receive considerable attention from the media and the Reserve Bank and some commentators have argued that there is an Australian property bubble.

The Australian property bubble is the economic theory that the Australian property market has become or is becoming significantly overpriced and due for a significant downturn. Since the early 2010s, various commentators, including one Treasury official, have claimed the Australian property market is in a significant bubble.

Northam Senior High School is a comprehensive public co-educational high school, located in Northam, a regional centre in the Wheatbelt region, 97 kilometres (60 mi) east of Perth, Western Australia.

PodProperty is an Australian online legal service provider that specializes in co-ownership agreements for tenants in common.

Paul Christopher Memmott is an Australian architect, anthropologist, academic and the Director of the Aboriginal Environments Research Centre at the University of Queensland. He is an expert on topics related to Indigenous architecture and vernacular architecture, housing, homelessness and overcrowding.

This Old Man Comes Rolling Home, Dorothy Hewett's first full-length play, was written in 1965. It captures the spirit and character of Redfern, an inner-city suburb of Sydney sometimes called "Australia's last slum". The play is a slice of life, following about six months in the life of the Dockertys, an extended family of seven children and partners, during the early 1950s. The family is subject to various stresses, most significantly because the mother is an alcoholic, largely lost in dreams of her youth.

Bonbons and Roses for Dolly, Dorothy Hewett's fourth full-length play, was written in 1971, soon after The Chapel Perilous. It begins with the rise to riches of three generations of a family, and the opening of their new picture house, the Crystal Palace. Over the years the cinema descends into ruin. The daughter Dolly inherits the decaying theatre. She symbolically shoots her grandparents and parents, then herself, as her dreams crumble.

Judith Nancy Yates was an Australian housing economist. She was a lecturer and associate professor at the University of Sydney from 1971 to 2009. As a social liberal economist, she published over 120 papers in academic journals and government and industry reports on most aspects of Australia's housing sector, most notably on distributional aspects of the tax and finance system, on affordability and the supply of low-rent housing.Throughout her career she was appointed to a number of government advisory committees, and she contributed to many government inquiries.

The Tatty Hollow Story, Dorothy Hewett's fifth full-length play, and last of a series of expressionist plays, was written in 1974 after Hewett's move from Perth to Sydney.

What About the People! is a joint 1950 book of verse by Dorothy Hewett (1923-2002) and Merv Lilley (1919-2014). It was the first book-length publication of poetry by either poet. What About the People! represented much of their significant output up to that time. The 1962 reprinting contained 43 poems by Lilley and 31 by Hewett, with one poem probably composed jointly.

Bobbin Up was the first novel by the author Dorothy Hewett (1923-2002). It is set in 1957 in a spinning mill in Alexandria, an industrial suburb of inner Sydney, and describes the lives of fifteen working-class women who work there for breadline wages. The novel is a series of loosely connected vignettes, where the life of each woman and her family is described within one or two chapters. The book concludes with a stay-in strike by the women for reinstatement after a mass layoff. Most of the group appear together in the final chapter.

The Fields of Heaven is a play written by Dorothy Hewett in 1982. It shows the gradual destruction of a once-beautiful country property in the Great Southern district of Western Australia, Marvel Locke, due to overgrazing and rising salt. In Act 1 it is tree-covered with fields of wheat like "cloth of gold". In Act 2, only a few straggling trees remain. Evocative bush sounds give way to harsh crow calls.