Related Research Articles

In archaeology,a hammerstone is a hard cobble used to strike off lithic flakes from a lump of tool stone during the process of lithic reduction. The hammerstone is a rather universal stone tool which appeared early in most regions of the world including Europe,India and North America. This technology was of major importance to prehistoric cultures before the age of metalworking.

In archaeology,in particular of the Stone Age,lithic reduction is the process of fashioning stones or rocks from their natural state into tools or weapons by removing some parts. It has been intensely studied and many archaeological industries are identified almost entirely by the lithic analysis of the precise style of their tools and the chaîne opératoire of the reduction techniques they used.

In lithic analysis,a subdivision of archaeology,a bulb of applied force is a defining characteristic of a lithic flake. Bulb of applied force was first correctly described by Sir John Evans,the cofounder of prehistoric archeology. However,bulb of percussion was coined scientifically by W.J. Sollas. When a flake is detached from its parent core,a portion of the Hertzian cone of force caused by the detachment blow is detached with it,leaving a distinctive bulb on the flake and a corresponding flake scar on the core. In the case of a unidirectional core,the bulb of applied force is produced by an initiated crack formed at the point of contact,which begins producing the Hertzian cone. The outward pressure increases causing the crack to curve away from the core and the bulb formation. The bulb of applied force forms below the striking platform as a slight bulge. If the flake is completely crushed the bulb will not be visible. Bulbs of applied force may be distinctive,moderate,or diffuse,depending upon the force of the blow used to detach the flake,and upon the type of material used as a fabricator. The bulb of applied force can indicate the mass or density of the tool used in the application of the force. The bulb may also be an indication of the angle of the force. This information is helpful to archaeologists in understanding and recreating the process of flintknapping. Generally,the harder the material used as a fabricator,the more distinctive the bulb of applied force. Soft hammer percussion has a low diffuse bulb while hard hammer percussion usually leaves a more distinct and noticeable bulb of applied force. Pressure flake also allowed for diffuse bulbs. The bulb of percussion of a flake or blade is convex and the core has a corresponding concave bulb. The concave bulb on the core is known as the negative bulb of percussion. Bulbs of applied force are not usually present if the flake has been struck off naturally. This allows archaeologists to identify and distinguish natural breakage from human artistry. The three main bulb types are flat or nondescript,normal,and pronounced. A flat or nondescript bulb is poorly defined and does not rise up on the ventral surface. A normal bulb on the ventral side has average height and well-defined. A pronounced bulb rises up on ventral side and is very large.

In archaeological terminology,a projectile point is an object that was hafted to a weapon that was capable of being thrown or projected,such as a javelin,dart,or arrow. They are thus different from weapons presumed to have been kept in the hand,such as knives,spears,axes,hammers,and maces.

Knapping is the shaping of flint,chert,obsidian,or other conchoidal fracturing stone through the process of lithic reduction to manufacture stone tools,strikers for flintlock firearms,or to produce flat-faced stones for building or facing walls,and flushwork decoration. The original Germanic term knopp meant to strike,shape,or work,so it could theoretically have referred equally well to making statues or dice. Modern usage is more specific,referring almost exclusively to the hand-tool pressure-flaking process pictured. It is distinguished from the more general verb "chip" and is different from "carve",and "cleave".

Experimental archaeology is a field of study which attempts to generate and test archaeological hypotheses,usually by replicating or approximating the feasibility of ancient cultures performing various tasks or feats. It employs a number of methods,techniques,analyses,and approaches,based upon archaeological source material such as ancient structures or artifacts.

In archaeology,lithic analysis is the analysis of stone tools and other chipped stone artifacts using basic scientific techniques. At its most basic level,lithic analyses involve an analysis of the artifact's morphology,the measurement of various physical attributes,and examining other visible features.

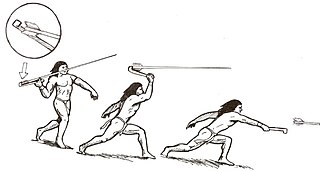

A spear-thrower,spear-throwing lever,or atlatl is a tool that uses leverage to achieve greater velocity in dart or javelin-throwing,and includes a bearing surface that allows the user to store energy during the throw.

A hand axe is a prehistoric stone tool with two faces that is the longest-used tool in human history. It is made from stone,usually flint or chert that has been "reduced" and shaped from a larger piece by knapping,or hitting against another stone. They are characteristic of the lower Acheulean and middle Palaeolithic (Mousterian) periods,roughly 1.6 million years ago to about 100,000 years ago,and used by Homo erectus and other early humans,but rarely by Homo sapiens.

In archaeology,a denticulate tool is a stone tool containing one or more edges that are worked into multiple notched shapes,much like the toothed edge of a saw. Such tools have been used as saws for woodworking,processing meat and hides,craft activities and for agricultural purposes. Denticulate tools were used by many different groups worldwide and have been found at a number of notable archaeological sites. They can be made from a number of different lithic materials,but a large number of denticulate tools are made from flint.

In archaeology,a blade is a type of stone tool created by striking a long narrow flake from a stone core. This process of reducing the stone and producing the blades is called lithic reduction. Archaeologists use this process of flintknapping to analyze blades and observe their technological uses for historical purposes.

The Levallois technique is a name given by archaeologists to a distinctive type of stone knapping developed around 250,000 to 300,000 years ago during the Middle Palaeolithic period. It is part of the Mousterian stone tool industry,and was used by the Neanderthals in Europe and by modern humans in other regions such as the Levant.

Don E. Crabtree was an American flintknapper and pioneering experimental archaeologist.

In archaeology,lithic technology includes a broad array of techniques used to produce usable tools from various types of stone. The earliest stone tools to date have been found at the site of Lomekwi 3 (LOM3) in Kenya and they have been dated to around 3.3 million years ago. The archaeological record of lithic technology is divided into three major time periods:the Paleolithic,Mesolithic,and Neolithic. Not all cultures in all parts of the world exhibit the same pattern of lithic technological development,and stone tool technology continues to be used to this day,but these three time periods represent the span of the archaeological record when lithic technology was paramount. By analysing modern stone tool usage within an ethnoarchaeological context,insight into the breadth of factors influencing lithic technologies in general may be studied. See:Stone tool. For example,for the Gamo of Southern Ethiopia,political,environmental,and social factors influence the patterns of technology variation in different subgroups of the Gamo culture;through understanding the relationship between these different factors in a modern context,archaeologists can better understand the ways that these factors could have shaped the technological variation that is present in the archaeological record.

In archaeology,a tranchet flake is a characteristic type of flake removed by a flintknapper during lithic reduction. Known as one of the major categories in core-trimming flakes,the making of a tranchet flake involves removing a flake parallel to the final intended cutting edge of the tool which creates a single straight edge as wide as the tool itself. A large flint artifact with a chisel-end,the tranchet flake has a cutting edge that is sharp and straight. The cutting edge is unmodified in most cases;sometimes,it is polished for increased durability and/or sharpness.

In archaeology,a flake tool is a type of stone tool that was used during the Stone Age that was created by striking a flake from a prepared stone core. People during prehistoric times often preferred these flake tools as compared to other tools because these tools were often easily made,could be made to be extremely sharp &could easily be repaired. Flake tools could be sharpened by retouch to create scrapers or burins. These tools were either made by flaking off small particles of flint or by breaking off a large piece and using that as a tool itself. These tools were able to be made by this "chipping" away effect due to the natural characteristic of stone. Stone is able to break apart when struck near the edge. Flake tools are created through flint knapping,a process of producing stone tools using lithic reduction.

In archaeology,debitage is all the material produced during the process of lithic reduction –the production of stone tools and weapons by knapping stone. This assemblage may include the different kinds of lithic flakes and lithic blades,but most often refers to the shatter and production debris,and production rejects.

Harold Lewis Dibble was an American Paleolithic archaeologist. His main research concerned the lithic reduction during which he conducted fieldwork in France,Egypt,and Morocco. He was a professor of Anthropology at the University of Pennsylvania and Curator-in-Charge of the European Section of the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology.

Errett Callahan was an American archaeologist,flintknapper,and pioneer in the fields of experimental archaeology and lithic replication studies.

Nicholas Patrick Toth is an American archaeologist and paleoanthropologist. He is a Professor in the Cognitive Science Program at Indiana University and is a founder and co-director of the Stone Age Institute. Toth's archaeological and experimental research has focused on the stone tool technology of Early Stone Age hominins who produced Oldowan and Acheulean artifacts which have been discovered across Africa,Asia,the Middle East,and Europe. He is best known for his experimental work,with Kathy Schick,including their work with the bonobo Kanzi who they taught to make and use simple stone tools similar to those made by our Early Stone Age ancestors.

References

- 1 2 3 "John Whittaker - Cirriculum Vitae". Academia.edu. Retrieved 2019-09-08.

- ↑ Whittaker, John (1994). Flintknapping: Making and Understanding Stone Tools. Austin: University of Texas Press. p. 223. ISBN 9780292790834.

- 1 2 "John C. Whittaker". Grinnell College . Retrieved 2019-09-08.

- ↑ (PDF) http://waa.basketmakeratlatl.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/02/Atlatl-elbow.pdf.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|title=(help)