Related Research Articles

Balša Balšić died September 18, 1385) or Balša II was the Lord of Lower Zeta from 1378 to 1385. He was a member of the Balšić noble family, which ruled Zeta from c. 1362 to 1421.

Gjon Kastrioti was an Albanian feudal lord from the House of Kastrioti and the father of Albanian leader Gjergj Kastrioti. He governed the territory between the Cape of Rodon and Dibër and had at his disposal an army of 2,000 horsemen.

Stracimir Balšić or Strazimir Balsha fl. 1360 – 15 January 1373) was a Lord of Zeta, alongside his two brothers Đurađ I and Balša II, in ca. 1362–1372. The Balšić family took over Zeta, by 1362, during the fall of the Serbian Empire. Stracimir took monastic vows and died in 1373. He left three sons, one of whom later became the Lord of Zeta.

The Kastrioti were an Albanian noble family, active in the 14th and 15th centuries as the rulers of the Principality of Kastrioti. At the beginning of the 15th century, the family controlled a territory in the Mat and Dibra regions. The most notable member was Gjergj Kastrioti, better known as Skanderbeg, regarded today as an Albanian hero for leading the resistance against Mehmed the Conqueror's efforts to expand the Ottoman Empire into Albania. After Skanderbeg's death and the fall of the Principality in 1468, the Kastrioti family gave their allegiance to the Kingdom of Naples and were given control over the Duchy of San Pietro in Galatina and the County of Soleto, now in the Province of Lecce, Italy. Ferrante, son of Gjon Kastrioti II, Duke of Galatina and Count of Soleto, is the direct ancestor of all male members of the Kastrioti family today. Today, the family consists of two Italian branches, one in Lecce and the other in Naples. The descendants of the House of Kastrioti in Italy use the family name "Castriota Scanderbeg".

Gjergj Kastrioti, commonly known as Skanderbeg, was an Albanian feudal lord and military commander who led a rebellion against the Ottoman Empire in what is today Albania, North Macedonia, Greece, Kosovo, Montenegro, and Serbia.

The Principality of Kastrioti was one of the Albanian principalities during the Late Middle Ages. It was formed by Pal Kastrioti who ruled it until 1407, after which his son, Gjon Kastrioti ruled until his death in 1437 and then ruled by the national hero of Albania, Skanderbeg.

The term Albanian Principalities refers to a number of principalities created in the Middle Ages in Albania and the surrounding regions in the western Balkans that were ruled by Albanian nobility. The 12th century marked the first Albanian principality, the Principality of Arbanon. It was later, however, in the 2nd half of the 14th century that these principalities became stronger, especially with the fall of the Serbian Empire after 1355. Some of these principalities were notably united in 1444 under the military alliance called League of Lezhë up to 1480 which defeated the Ottoman Empire in more than 28 battles. They covered modern day Albania,western and central Kosovo, Epirus, areas up to Corinth, western North Macedonia, southern Montenegro. The leaders of these principalities were some of the most noted Balkan figures in the 14th and 15th centuries such as Gjin Bua Shpata, Andrea II Muzaka, Gjon Zenebishi, Karl Topia, Andrea Gropa, Balsha family, Gjergj Arianiti, Gjon Kastrioti, Skanderbeg, Dukagjini family and Lek Dukagjini.

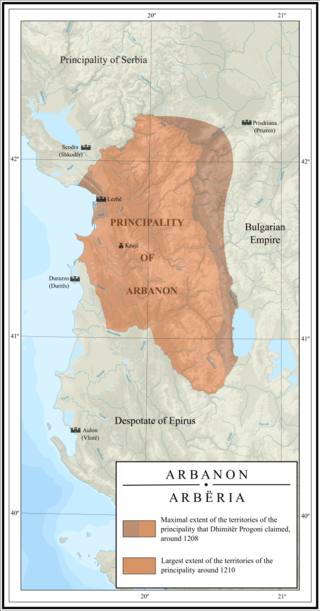

Arbanon was a medieval principality in present-day Albania, ruled by the native Progoni family, and the first Albanian state to emerge in recorded history. The principality was established in 1190 by the Albanian archon Progon in the region surrounding Kruja, to the east and northeast of Venetian territories. Progon was succeeded by his sons Gjin and then Demetrius (Dhimitër), who managed to retain a considerable degree of autonomy from the Byzantine Empire. In 1204, Arbanon attained full, though temporary, political independence, taking advantage of the weakening of Constantinople following its pillage during the Fourth Crusade. However, Arbanon lost its large autonomy ca. 1216, when the ruler of Epirus, Michael I Komnenos Doukas, started an invasion northward into Albania and Macedonia, taking Kruja and ending the independence of the principality. From this year, after the death of Demetrius, the last ruler of the Progoni family, Arbanon was successively controlled by the Despotate of Epirus, then by the Bulgarian Empire and, from 1235, by the Empire of Nicaea.

The Principality of Albania was an Albanian principality ruled by the Albanian dynasty of Thopia. The first notable ruler was Tanusio Thopia, who became Count of Mat in 1328. The principality would reach its zenith during the rule of Karl Thopia, who emerged in 1359 after the Battle of Achelous, conquering the cities of Durrës and Krujë and consolidating his rule of central Albania between the rivers of Mat and Shkumbin. The principality would last up until 1415, when it was conquered by the Ottoman Empire.

The Great Warrior Skanderbeg is a 1953 Soviet-Albanian biopic directed by Sergei Yutkevich. It was entered into the 1954 Cannes Film Festival where it earned the International Prize. Yutkevich also earned the Special Mention award for his direction.

The Principality of Valona and Kanina, also known as the Despotate of Valona and Kanina, Principality of Valona or Principality of Vlorë (1346–1417) was a medieval principality in Albania, roughly encompassing the territories of the modern counties of Vlorë (Valona), Fier, and Berat. Initially a vassal of the Serbian Empire, it became an independent lordship after 1355, although de facto under Venetian influence, and remained as such until it was conquered by the Ottoman Turks in 1417.

Skanderbeg's Italian expedition (1460–1462) was undertaken to aid his ally Ferdinand I of Naples, whose rulership was threatened by the Angevin Dynasty. Gjergj Kastrioti Skanderbeg was the ruler of Albania who had been leading a rebellion against the Ottoman Empire since 1443 and allied himself with several European monarchs in order to consolidate his domains. In 1458, Alfonso V of Aragon, ruler of Sicily and Naples and Skanderbeg's most important ally, died, leaving his illegitimate son, Ferdinand, on the Neapolitan throne; René d'Anjou, the French Duke of Anjou, laid claim to the throne. The conflict between René's and Ferdinand's supporters soon erupted into a civil war. Pope Calixtus III, of Spanish background himself, could do little to secure Ferdinand, so he turned to Skanderbeg for aid.

Voisava was a noblewoman and wife of Gjon Kastrioti, an Albanian feudal lord from the House of Kastrioti. They had nine children together, one of whom was the Albanian national hero Gjergj Kastrioti, better known as Skanderbeg.

The Myth of Skanderbeg is one of the main constitutive myths of Albanian nationalism. In the late nineteenth century during the Albanian struggle and the Albanian National Awakening, Skanderbeg became a symbol for the Albanians and he was turned into a national Albanian hero and myth.

John Komnenos Asen was the ruler of the Principality of Valona from c. 1345 to 1363, initially as a vassal of the Serbian Empire, and after 1355 as a largely independent lord. Descended from high-ranking Bulgarian nobility, John was a brother of both Tsar Ivan Alexander of Bulgaria and Helena of Bulgaria, the wife of Tsar Stephen Dušan of Serbia. Perhaps in search of better opportunities, he emigrated to Serbia, where his sister was married. There, he was granted the title of despot by Stephen Dušan, who placed him in charge of his territories in modern south Albania.

Pal or Gjergj Kastrioti was an Albanian medieval ruler in the latter part of the 14th century in northern Albania. Not much is known about his life. He is mentioned in only two historical sources which describe his rule as extending in a region between Mat and Dibër. His son was Gjon Kastrioti and his grandson Skanderbeg, the Albanian national hero.

Mrkša Žarković was a Serbian nobleman who ruled parts of today's southern Albania from 1396 to 1414.

Aleks Buda was an Albanian historian. After completion of his education in Italy and Austria, he returned to Albania. Although his education was in literature, he made a career as a historian during the socialist period in Albania. He was a member and president of the Academy of Sciences of Albania.

Shufada was a medieval trade port in northern Albania. It was near the mouth of a river, with academics proposing Mat, Ishëm and Erzen. It was at the time one among a string of ports in Albania that enjoyed prosperity and economic significance until being abandoned at the start of the Ottoman period. A 1420 commercial treaty between Gjon Kastrioti and the Republic of Ragusa shows that Shufada was the main customs port for the former's domains.

Comita Muzaka, also known as Komnina, Komnena or Komnene was an Albanian princess and member of the Muzaka family.

References

- ↑ Soulis 1984, p. 137.

- ↑ Ducellier 1981, p. 523.

- 1 2 Soulis 1984 , p. 138

- ↑ Soulis 1984, p. 253.

- 1 2 Omari 2014 , p. 29

- ↑ Ducellier 1981, p. 620.

- ↑ Hodgkinson 1999, p. 224.

- ↑ Kretschmayr, Heinrich (1920). Geschichte von Venedig (in German). Vol. 2. Gotha: F.A. Perthes. p. 375. OCLC 39124645.

- ↑ Buda 1986, p. 239.

- ↑ Fine 1994, p. 357.

- ↑ Omari 2014, p. 46.