Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) is a clear, colorless body fluid found within the tissue that surrounds the brain and spinal cord of all vertebrates.

Viral meningitis, also known as aseptic meningitis, is a type of meningitis due to a viral infection. It results in inflammation of the meninges. Symptoms commonly include headache, fever, sensitivity to light and neck stiffness.

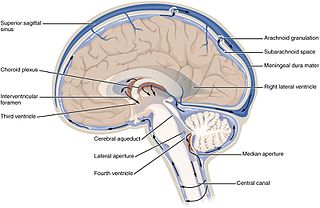

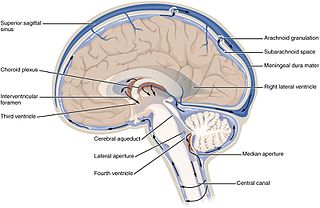

Hydrocephalus is a condition in which an accumulation of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) occurs within the brain. This typically causes increased pressure inside the skull. Older people may have headaches, double vision, poor balance, urinary incontinence, personality changes, or mental impairment. In babies, it may be seen as a rapid increase in head size. Other symptoms may include vomiting, sleepiness, seizures, and downward pointing of the eyes.

The ventricular system is a set of four interconnected cavities known as cerebral ventricles in the brain. Within each ventricle is a region of choroid plexus which produces the circulating cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). The ventricular system is continuous with the central canal of the spinal cord from the fourth ventricle, allowing for the flow of CSF to circulate.

Lumbar puncture (LP), also known as a spinal tap, is a medical procedure in which a needle is inserted into the spinal canal, most commonly to collect cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) for diagnostic testing. The main reason for a lumbar puncture is to help diagnose diseases of the central nervous system, including the brain and spine. Examples of these conditions include meningitis and subarachnoid hemorrhage. It may also be used therapeutically in some conditions. Increased intracranial pressure is a contraindication, due to risk of brain matter being compressed and pushed toward the spine. Sometimes, lumbar puncture cannot be performed safely. It is regarded as a safe procedure, but post-dural-puncture headache is a common side effect if a small atraumatic needle is not used.

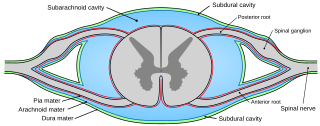

Pia mater, often referred to as simply the pia, is the delicate innermost layer of the meninges, the membranes surrounding the brain and spinal cord. Pia mater is medieval Latin meaning "tender mother". The other two meningeal membranes are the dura mater and the arachnoid mater. Both the pia and arachnoid mater are derivatives of the neural crest while the dura is derived from embryonic mesoderm. The pia mater is a thin fibrous tissue that is permeable to water and small solutes. The pia mater allows blood vessels to pass through and nourish the brain. The perivascular space between blood vessels and pia mater is proposed to be part of a pseudolymphatic system for the brain. When the pia mater becomes irritated and inflamed the result is meningitis.

Spinal anaesthesia, also called spinal block, subarachnoid block, intradural block and intrathecal block, is a form of neuraxial regional anaesthesia involving the injection of a local anaesthetic or opioid into the subarachnoid space, generally through a fine needle, usually 9 cm (3.5 in) long. It is a safe and effective form of anesthesia usually performed by anesthesiologists that can be used as an alternative to general anesthesia commonly in surgeries involving the lower extremities and surgeries below the umbilicus. The local anesthetic with or without an opioid injected into the cerebrospinal fluid provides locoregional anaesthesia: true analgesia, motor, sensory and autonomic (sympathetic) blockade. Administering analgesics in the cerebrospinal fluid without a local anaesthetic produces locoregional analgesia: markedly reduced pain sensation, some autonomic blockade, but no sensory or motor block. Locoregional analgesia, due to mainly the absence of motor and sympathetic block may be preferred over locoregional anaesthesia in some postoperative care settings. The tip of the spinal needle has a point or small bevel. Recently, pencil point needles have been made available.

Congenital syphilis is syphilis that occurs when a mother with untreated syphilis passes the infection to her baby during pregnancy or at birth. It may present in the unborn baby, newborn baby or later. Clinical features vary and differ between early onset, that is presentation before age 2-years of age, and late onset, presentation after age 2-years. Infection in the unborn baby may present as poor growth, non-immune hydrops leading to premature birth or loss of the baby, or no signs. Affected newborns mostly initially have no clinical signs. They may be small and irritable. Characteristic features include a rash, fever, large liver and spleen, a runny and congested nose, and inflammation around bone or cartilage. There may be jaundice, large glands, pneumonia, meningitis, warty bumps on genitals, deafness or blindness. Untreated babies that survive the early phase may develop skeletal deformities including deformity of the nose, lower legs, forehead, collar bone, jaw, and cheek bone. There may be a perforated or high arched palate, and recurrent joint disease. Other late signs include linear perioral tears, intellectual disability, hydrocephalus, and juvenile general paresis. Seizures and cranial nerve palsies may first occur in both early and late phases. Eighth nerve palsy, interstitial keratitis and small notched teeth may appear individually or together; known as Hutchinson's triad.

Arachnoiditis is an inflammatory condition of the arachnoid mater or 'arachnoid', one of the membranes known as meninges that surround and protect the nerves of the central nervous system, including the brain and spinal cord. The arachnoid can become inflamed because of adverse reactions to chemicals, infection from bacteria or viruses, as the result of direct injury to the spine, chronic compression of spinal nerves, complications from spinal surgery or other invasive spinal procedures, or the accidental intrathecal injection of steroids intended for the epidural space. Inflammation can sometimes lead to the formation of scar tissue and adhesion that can make the spinal nerves "stick" together, a condition where such tissue develops in and between the leptomeninges. The condition is extremely painful, especially when progressing to adhesive arachnoiditis. Another form of the condition is arachnoiditis ossificans, in which the arachnoid becomes ossified, or turns to bone, and is thought to be a late-stage complication of the adhesive form of arachnoiditis.

Intrathecal administration is a route of administration for drugs via an injection into the spinal canal, or into the subarachnoid space so that it reaches the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and is useful in spinal anesthesia, chemotherapy, or pain management applications. This route is also used to introduce drugs that fight certain infections, particularly post-neurosurgical. The drug needs to be given this way to avoid being stopped by the blood–brain barrier. The same drug given orally must enter the blood stream and may not be able to pass out and into the brain. Drugs given by the intrathecal route often have to be compounded specially by a pharmacist or technician because they cannot contain any preservative or other potentially harmful inactive ingredients that are sometimes found in standard injectable drug preparations.

Myelography is a type of radiographic examination that uses a contrast medium to detect pathology of the spinal cord, including the location of a spinal cord injury, cysts, and tumors. Historically the procedure involved the injection of a radiocontrast agent into the cervical or lumbar spine, followed by several X-ray projections. Today, myelography has largely been replaced by the use of MRI scans, although the technique is still sometimes used under certain circumstances – though now usually in conjunction with CT rather than X-ray projections.

A Rich focus is a tuberculous granuloma occurring within the cortex or meninges of the brain that ruptures into the subarachnoid space, causing tuberculous meningitis. The Rich focus is named for Arnold Rice Rich, a pathologist at Johns Hopkins Hospital, who along with his colleague Howard McCordock first described the post-mortem finding of caseous foci within the cerebral cortex or meninges which appeared to predate the development of meningitis. Prior to their research the prevailing view had been that meningitis occurred as a result of the dissemination of tuberculous bacilli associated with miliary tuberculosis and that these processes occurred at the same time.

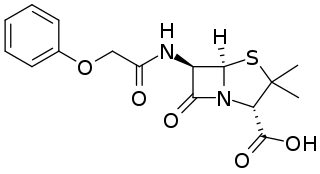

Phenoxymethylpenicillin, also known as penicillin V (PcV) and penicillin VK, is an antibiotic useful for the treatment of a number of bacterial infections. Specifically it is used for the treatment of strep throat, otitis media, and cellulitis. It is also used to prevent rheumatic fever and to prevent infections following removal of the spleen. It is given by mouth.

Leptomeningeal cancer is a rare complication of cancer in which the disease spreads from the original tumor site to the meninges surrounding the brain and spinal cord. This leads to an inflammatory response, hence the alternative names neoplastic meningitis (NM), malignant meningitis, or carcinomatous meningitis. The term leptomeningeal describes the thin meninges, the arachnoid and the pia mater, between which the cerebrospinal fluid is located. The disorder was originally reported by Eberth in 1870.

A pneumococcal infection is an infection caused by the bacterium Streptococcus pneumoniae, which is also called the pneumococcus. S. pneumoniae is a common member of the bacterial flora colonizing the nose and throat of 5–10% of healthy adults and 20–40% of healthy children. However, it is also a cause of significant disease, being a leading cause of pneumonia, bacterial meningitis, and sepsis. The World Health Organization estimates that in 2005 pneumococcal infections were responsible for the death of 1.6 million children worldwide.

Meningitis is acute or chronic inflammation of the protective membranes covering the brain and spinal cord, collectively called the meninges. The most common symptoms are fever, headache, and neck stiffness. Other symptoms include confusion or altered consciousness, nausea, vomiting, and an inability to tolerate light or loud noises. Young children often exhibit only nonspecific symptoms, such as irritability, drowsiness, or poor feeding. A non-blanching rash may also be present.

Drug-Induced Aseptic Meningitis (DIAM) is a type of aseptic meningitis related to the use of medications such as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) or biologic drugs such as intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG). Additionally, this condition generally shows clinical improvement after cessation of the medication, as well as a tendency to relapse with resumption of the medication.

Austrian syndrome, also known as Osler's triad, is a medical condition that was named after Robert Austrian in 1957. The presentation of the condition consists of pneumonia, endocarditis, and meningitis, all caused by Streptococcus pneumoniae. It is associated with alcoholism due to hyposplenism and can be seen in males between the ages of 40 and 60 years old. Robert Austrian was not the first one to describe the condition, but Richard Heschl or William Osler were not able to link the signs to the bacteria because microbiology was not yet developed.

Bailey v Ministry of Defence [2008] EWCA Civ 883 is an English tort law case. It concerns the problematic question of factual causation, and the interplay of the "but for" test and its relaxation through a "material contribution" test.

Honor Mildred Vivian Smith was an English neurologist who specialised in the treatment of tuberculous meningitis. She worked and taught at the teaching hospitals of the University of Oxford, and was appointed OBE in 1962.