The ellipsis, rendered ..., alternatively described as suspension points/dots, points/periods of ellipsis, or ellipsis points, or colloquially, dot-dot-dot, is a punctuation mark consisting of a series of three dots. An ellipsis can be used in many ways, such as for intentional omission of text or numbers, to imply a concept without using words. Style guides differ on how to render an ellipsis in printed material.

An orthography is a set of conventions for writing a language, including norms of spelling, punctuation, word boundaries, capitalization, hyphenation, and emphasis.

The comma, is a punctuation mark that appears in several variants in different languages. Some typefaces render it as a small line, slightly curved or straight, but inclined from the vertical, others give it the appearance of a miniature filled-in figure 9 placed on the baseline. In many typefaces it is the same shape as an apostrophe or single closing quotation mark ’.

The apostrophe is a punctuation mark, and sometimes a diacritical mark, in languages that use the Latin alphabet and some other alphabets. In English, the apostrophe is used for three basic purposes:

A bracket is either of two tall fore- or back-facing punctuation marks commonly used to isolate a segment of text or data from its surroundings. They come in four main pairs of shapes, as given in the box to the right, which also gives their names, that vary between British and American English. "Brackets", without further qualification, are in British English the (...) marks and in American English the [...] marks.

In English writing, quotation marks or inverted commas, also known informally as quotes, talking marks, speech marks, quote marks, quotemarks or speechmarks, are punctuation marks placed on either side of a word or phrase in order to identify it as a quotation, direct speech or a literal title or name. Quotation marks may be used to indicate that the meaning of the word or phrase they surround should be taken to be different from that typically associated with it, and are often used in this way to express irony. They are also sometimes used to emphasise a word or phrase, although this is usually considered incorrect.

In the English language, there are grammatical constructions that many native speakers use unquestioningly yet certain writers call incorrect. Differences of usage or opinion may stem from differences between formal and informal speech and other matters of register, differences among dialects, difference between the social norms of spoken and written English, and so forth. Disputes may arise when style guides disagree with each other, when an older standard gradually loses traction, or when a guideline or judgement is confronted by large amounts of conflicting evidence or has its rationale challenged.

"Between you and I" is an English phrase that has drawn considerable interest from linguists, grammarians, and stylists. It is commonly used by style guides as a convenient label for a construction where the nominative/subjective form of pronouns is used for two pronouns joined by and in circumstances where the accusative/oblique case would be used for a single pronoun, typically following a preposition, but also as the object of a transitive verb. One frequently cited use of the phrase occurs in Shakespeare's The Merchant of Venice (1596–98). According to many style guides, the Shakespearian character who used the phrase should have written "between you and me". Use of this common construction has been described as "a grammatical error of unsurpassable grossness", although whether it is in fact an error is a matter of debate.

The serial comma is a comma placed after the second-to-last term in a list when writing out three or more terms. For example, a list of three countries might be punctuated without the serial comma as "France, Italy and Spain" or with the serial comma as "France, Italy, and Spain". The serial comma can help avoid ambiguity in some situations, but can also create it in others. There is no universally accepted standard for when to use the serial comma.

In written English usage, a comma splice or comma fault is the use of a comma to join two independent clauses. For example:

It is nearly half past five, we cannot reach town before dark.

Scare quotes are quotation marks that writers place around a word or phrase to signal that they are using it in an ironic, referential, or otherwise non-standard sense. Scare quotes may indicate that the author is using someone else's term, similar to preceding a phrase with the expression "so-called"; they may imply skepticism or disagreement, belief that the words are misused, or that the writer intends a meaning opposite to the words enclosed in quotes. Whether quotation marks are considered scare quotes depends on context because scare quotes are not visually different from actual quotations. The use of scare quotes is sometimes discouraged in formal or academic writing.

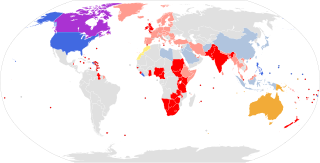

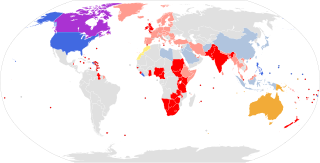

Despite the various English dialects spoken from country to country and within different regions of the same country, there are only slight regional variations in English orthography, the two most notable variations being British and American spelling. Many of the differences between American and British or Commonwealth English date back to a time before spelling standards were developed. For instance, some spellings seen as "American" today were once commonly used in Britain, and some spellings seen as "British" were once commonly used in the United States.

A compound modifier is a compound of two or more attributive words: that is, two or more words that collectively modify a noun. Compound modifiers are grammatically equivalent to single-word modifiers and can be used in combination with other modifiers.

Guillemets are a pair of punctuation marks in the form of sideways double chevrons, « and », used as quotation marks in a number of languages. In some of these languages, "single" guillemets, ‹ and ›, are used for a quotation inside another quotation. Guillemets are not conventionally used in English.

Quotation marks are punctuation marks used in pairs in various writing systems to identify direct speech, a quotation, or a phrase. The pair consists of an opening quotation mark and a closing quotation mark, which may or may not be the same glyph. Quotation marks have a variety of forms in different languages and in different media.

The dash is a punctuation mark consisting of a long horizontal line. It is similar in appearance to the hyphen but is longer and sometimes higher from the baseline. The most common versions are the en dash–, generally longer than the hyphen but shorter than the minus sign; the em dash—, longer than either the en dash or the minus sign; and the horizontal bar―, whose length varies across typefaces but tends to be between those of the en and em dashes.

A false, coined, fake, bogus or pseudo-title, also called a Time-style adjective and an anarthrous nominal premodifier, is a kind of preposed appositive phrase before a noun predominantly found in journalistic writing. It formally resembles a title, in that it does not start with an article, but is a common noun phrase, not a title. An example is the phrase convicted bomber in "convicted bomber Timothy McVeigh", rather than "the convicted bomber Timothy McVeigh".

The full stop, period, or full point. is a punctuation mark used for several purposes, most often to mark the end of a declarative sentence.