A kern was a Gaelic warrior, specifically a light infantryman, in Ireland in the Middle Ages.

A kern was a Gaelic warrior, specifically a light infantryman, in Ireland in the Middle Ages.

The word kern is an anglicisation of the Middle Irish word ceithern [ˈkʲeθʲern̪] or ceithrenn meaning a collection of persons, particularly fighting men. An individual member is a ceithernach. [1] The word may derive from a conjectural proto-Celtic word *keternā, ultimately from an Indo-European root meaning a chain. [2] Kern was adopted into English as a term for a Gaelic soldier in medieval Ireland and as cateran , meaning 'Highland marauder', 'bandit'. The term ceithernach is also used in modern Irish for a chess pawn.

Kerns notably accompanied bands of the mercenary gallowglasses as their light infantry forces, where the gallowglass filled the need for heavy infantry. This two-tier "army" structure though should not be taken to reflect earlier Irish armies prior to the Norman invasions, as there were more locally trained soldiers filling various roles prior to this. The gallowglass largely replaced the other forms of infantry though, as more Irish began to imitate them, creating gallowglass of purely Irish origin.

Earlier, the ceithern would have consisted of myriad militia-type infantry, and possibly light horse, most likely remembered later in the "horse boys" that accompanied gallowglass and fought as light cavalry. They would be armed from common stock or by what they owned themselves, usually with swords, shields, bows, javelins and filled out numerous portions of an army, probably forming the vast bulk of most Gaelic forces. In the mid-16th century Shane O'Neill was known to have armed his peasantry and Hugh O'Neill, Earl of Tyrone, outfitted many of his Ceithernn with contemporary battle dress and weapons and drilled them as a professional force, complete with experienced captains and modern weapons. [3] [4]

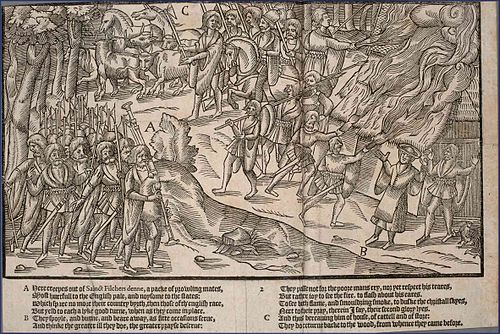

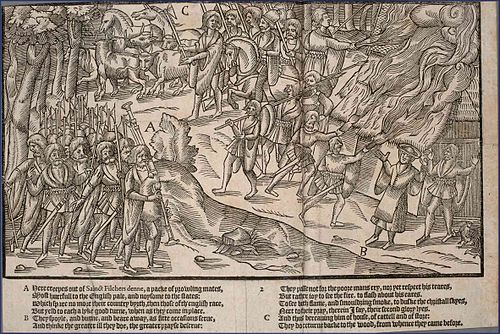

Jean Froissart (c. 1337–c. 1410) includes a description of the Irish wearing "very simple" armour (perhaps leather or fabric forms of protection). Kerns were light troops who relied on speed and mobility, often utilising lightning strike tactics as a force multiplier to engage much larger formations. In the words of one writer, they were, "lighter and lustier than [English soldiers] in travail and footmanship". [5] John Dymmok, who served in the retinue of the earl of Essex, Elizabeth I's lord lieutenant of Ireland, provides the classic description of a kern equipped for war: ". . . a kind of footman, slightly armed with a sword, a target (round shield) of wood, or a bow and sheaf of arrows with barbed heads, or else three darts, which they cast with a wonderful facility and nearness, a weapon more noisome to the enemy, especially horsemen, than it is deadly". Kerns were armed with a sword (claideamh), long dagger (scian), bow (bogha) and a set of javelins, or darts (ga). [6]

Kerns did not cling to their obsolete weapons and tactics but wholeheartedly and with great speed adopted weapons and military methodology of the continent, becoming heavily dependent upon firepower. However, they retained their original armaments and used them to great effect in areas where pike-and-shot formation was ineffective, such as woodland and dense scrub. [7]

Native Irish displaced by the Anglo-Norman invasion, operated as bandits in the forests of Ireland where they were known as "wood kerns" or cethern coille. [8] They were such a threat to the new settlers that a law was passed in 1297 requiring lords of the woods to keep the roads clear of fallen and growing trees, to make it harder for wood kerns to launch their attacks. [8]

Notably, Kerns appear in Shakespeare's Henry VI, Part 2 (1599):

Cardinal.

My Lord of York, try what your fortune is.

The uncivil kerns of Ireland are in arms,

And temper clay with blood of Englishmen.

To Ireland will you lead a band of men,

Collected choicely, from each county some,

And try your hap against the Irishmen? [9]

Shakespeare mentions kerns (and gallowglasses) in his play Macbeth (1606):

The merciless Macdonwald,

Worthy to be a rebel, for to that

The multiplying villainies of nature

Do swarm upon him, from the Western isles

Of kerns and gallowglasses is supplied

[10]

{{cite book}}: |last= has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)