Related Research Articles

In legal terminology, a complaint is any formal legal document that sets out the facts and legal reasons that the filing party or parties believes are sufficient to support a claim against the party or parties against whom the claim is brought that entitles the plaintiff(s) to a remedy. For example, the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure (FRCP) that govern civil litigation in United States courts provide that a civil action is commenced with the filing or service of a pleading called a complaint. Civil court rules in states that have incorporated the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure use the same term for the same pleading.

In law, interrogatories are a formal set of written questions propounded by one litigant and required to be answered by an adversary in order to clarify matters of fact and help to determine in advance what facts will be presented at any trial in the case.

A lawsuit is a proceeding by a party or parties against another in the civil court of law. The archaic term "suit in law" is found in only a small number of laws still in effect today. The term "lawsuit" is used in reference to a civil action brought by a plaintiff demands a legal or equitable remedy from a court. The defendant is required to respond to the plaintiff's complaint. If the plaintiff is successful, judgment is in the plaintiff's favor, and a variety of court orders may be issued to enforce a right, award damages, or impose a temporary or permanent injunction to prevent an act or compel an act. A declaratory judgment may be issued to prevent future legal disputes.

Hill v Church of Scientology of Toronto February 20, 1995- July 20, 1995. 2 S.C.R. 1130 was a libel case against the Church of Scientology, in which the Supreme Court of Canada interpreted Ontario's libel law in relation to the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms.

In United States law, a motion is a procedural device to bring a limited, contested issue before a court for decision. It is a request to the judge to make a decision about the case. Motions may be made at any point in administrative, criminal or civil proceedings, although that right is regulated by court rules which vary from place to place. The party requesting the motion may be called the moving party, or may simply be the movant. The party opposing the motion is the nonmoving party or nonmovant.

A subpoena duces tecum, or subpoena for production of evidence, is a court summons ordering the recipient to appear before the court and produce documents or other tangible evidence for use at a hearing or trial. In some jurisdictions, it can also be issued by legislative bodies such as county boards of supervisors.

Discovery, in the law of common law jurisdictions, is a pre-trial procedure in a lawsuit in which each party, through the law of civil procedure, can obtain evidence from the other party or parties by means of discovery devices such as interrogatories, requests for production of documents, requests for admissions and depositions. Discovery can be obtained from non-parties using subpoenas. When a discovery request is objected to, the requesting party may seek the assistance of the court by filing a motion to compel discovery.

The Federal Rules of Civil Procedure govern civil procedure in United States district courts. The FRCP are promulgated by the United States Supreme Court pursuant to the Rules Enabling Act, and then the United States Congress has seven months to veto the rules promulgated or they become part of the FRCP. The Court's modifications to the rules are usually based upon recommendations from the Judicial Conference of the United States, the federal judiciary's internal policy-making body.

United States v. Reynolds, 345 U.S. 1 (1953), is a landmark legal case in 1953 that saw the formal recognition of the state secrets privilege, a judicially recognized extension of presidential power.

The clergy–penitent privilege, clergy privilege, confessional privilege, priest–penitent privilege, pastor–penitent privilege, clergyman–communicant privilege, or ecclesiastical privilege, is a rule of evidence that forbids judicial inquiry into certain communications between clergy and members of their congregation. This rule recognises certain communication as privileged and not subject to otherwise obligatory disclosure; for example, this often applies to communications between lawyers and clients. In many jurisdictions certain communications between a member of the clergy of some or all religious faiths and a person consulting them in confidence are privileged in law. In particular, Catholics, Lutherans and Anglicans, among adherents of other Christian denominations, confess their sins to priests, who are unconditionally forbidden by Church canon law from making any disclosure, a position supported by the law of many countries, although in conflict with civil (secular) law in some jurisdictions. It is a distinct concept from that of confidentiality.

Stuart Jeff Rabner is the chief justice of the New Jersey Supreme Court. He served as New Jersey Attorney General, Chief Counsel to Governor Jon Corzine, and as a federal prosecutor at the U.S. Attorney's Office for the District of New Jersey.

In common law jurisdictions, legal professional privilege protects all communications between a professional legal adviser and his or her clients from being disclosed without the permission of the client. The privilege is that of the client and not that of the lawyer.

Hickman v. Taylor, 329 U.S. 495 (1947), is a United States Supreme Court case in which the Court recognized the work-product doctrine, which holds that information obtained or produced by or for attorneys in anticipation of litigation may be protected from discovery under the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure. The Court's decision in the case was unanimous.

In England and Wales, the principle of legal professional privilege has long been recognised by the common law. It is seen as a fundamental principle of justice, and grants a protection from disclosing evidence. It is a right that attaches to the client and so may only be waived by the client.

A Doe subpoena is a subpoena that seeks the identity of an unknown defendant to a lawsuit. Most jurisdictions permit a plaintiff who does not yet know a defendant's identity to file suit against John Doe and then use the tools of the discovery process to seek the defendant's true name. A Doe subpoena is often served on an online service provider or ISP for the purpose of identifying the author of an anonymous post.

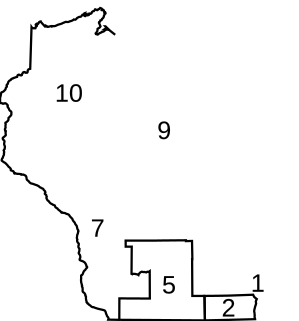

The Wisconsin circuit courts are the general trial courts in the state of Wisconsin. There are currently 69 circuits in the state, divided into 10 judicial administrative districts. Circuit court judges hear and decide both civil and criminal cases. Each of the 249 circuit court judges are elected and serve six-year terms.

Civil discovery under United States federal law is wide-ranging and can involve any material which is relevant to the case except information which is privileged, information which is the work product of the opposing party, or certain kinds of expert opinions. Electronic discovery or "e-discovery" is used when the material is stored on electronic media.

R v Basi is a landmark decision by Supreme Court of Canada where the Court weighed the rights of the defendant versus the privileges of an informant in an important trial into alleged government corruption.

In Phato v Attorney-General, Eastern Cape & Another; Commissioner of the South African Police Services v Attorney-General, Eastern Cape & Others, in two applications, which were combined for the purposes of the judgment, the issue was the right of an accused to access to the police docket relating to the accused's impending trial in a magistrate's court on a charge under the Witchcraft Suppression Act 3 of 1957.

The Evidence Act 2006 is an Act of the Parliament of New Zealand that codifies the laws of evidence. When enacted, the Act drew together the common law and statutory provisions relating to evidence into one comprehensive scheme, replacing most of the previous evidence law on the admissibility and use of evidence in court proceedings.

References

- Khala v Minister of Safety and Security 1994 (2) SACR 361 (W).