The Ku Klux Klan, commonly shortened to the KKK or the Klan, is an American Protestant-led Christian extremist, white supremacist, far-right hate group. It was founded in 1865 during Reconstruction in the devastated South. Various historians have characterized the Klan as America's first terrorist group. The group contains several organizations structured as a secret society, which have frequently resorted to terrorism, violence and acts of intimidation to impose their criteria and oppress their victims, most notably African Americans, Jews, and Catholics. There have been three distinct iterations with various other targets relative to time and place.

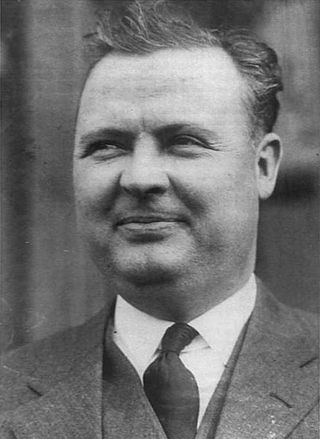

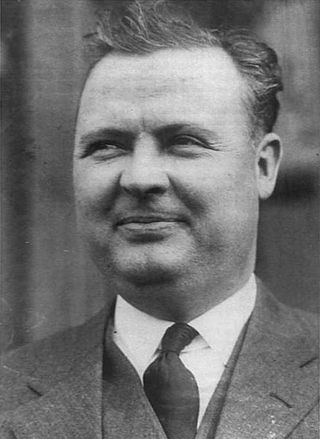

David Curtis "Steve" Stephenson was an American Ku Klux Klan leader, convicted rapist and murderer. In 1923 he was appointed Grand Dragon of the Indiana Klan and head of Klan recruiting for seven other states. Later that year, he led those groups to independence from the national KKK organization. Amassing wealth and political power in Indiana politics, he was one of the most prominent national Klan leaders. He had close relationships with numerous Indiana politicians, especially Governor Edward L. Jackson.

In modern times, cross burning or cross lighting is a practice which is associated with the Ku Klux Klan. However, it was practiced long before the Klan's inception. Since the early 20th century, the Klan burned crosses on hillsides as a way to intimidate and threaten Black Americans and other marginalized groups.

The Imperial Klans of America, Knights of the Ku Klux Klan (IKA) is a white supremacist, white nationalist, neo-Nazi paramilitary organization. Until the late 2000s, it was the second largest Klan group in the United States, and at one point in the early 2000s, it was the largest. In 2008, the IKA was reported to have at least 23 chapters in 17 states, most of which were small.

The grand wizard is the national leader of Ku Klux Klan organizations in the United States and abroad.

William Joseph Simmons was an American preacher and fraternal organizer who founded and led the second Ku Klux Klan from Thanksgiving evening 1915 until being ousted in 1922 by Hiram Wesley Evans.

James Arnold Colescott was an American white supremacist who was Imperial Wizard of the Knights of the Ku Klux Klan. Under financial pressure from the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) for back taxes, he disbanded the second wave of the original Ku Klux Klan in 1944.

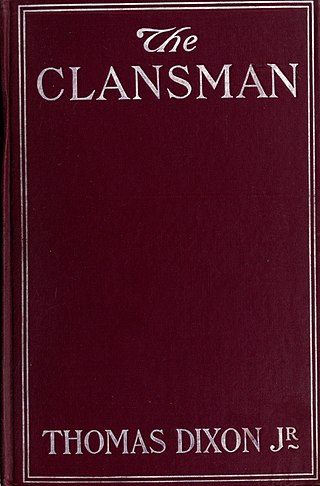

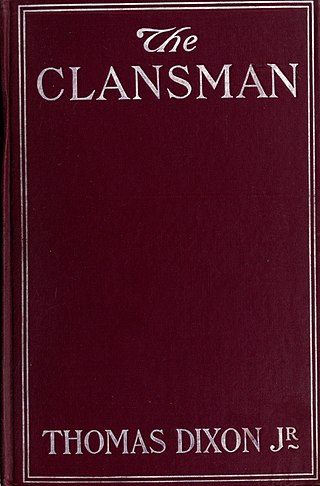

The Clansman: A Historical Romance of the Ku Klux Klan is a novel published in 1905, the second work in the Ku Klux Klan trilogy by Thomas Dixon Jr.. Chronicling the American Civil War and Reconstruction era from a pro-Confederate perspective, it presents the Ku Klux Klan heroically. The novel was adapted first by the author as a highly successful play entitled The Clansman (1905), and a decade later by D. W. Griffith in the 1915 movie The Birth of a Nation.

This is a partial list of notable historical figures in U.S. national politics who were members of the Ku Klux Klan before taking office. Membership of the Klan is secret. Political opponents sometimes allege that a person was a member of the Klan, or was supported at the polls by Klan members.

The White Knights of the Ku Klux Klan is a Ku Klux Klan (KKK) organization which is active in the United States. It originated in Mississippi and Louisiana in the early 1960s under the leadership of Samuel Bowers, its first Imperial Wizard. The White Knights of Mississippi were formed in December 1963, when they separated from the Original Knights of Mississippi after the resignation of Imperial Wizard Roy Davis. Roughly 200 members of the Original Knights of Louisiana also joined the White Knights. Within a year, their membership was up to around six thousand, and they had Klaverns in over half of the counties in Mississippi. By 1967, the number of active members had declined to around four hundred. Similar to the United Klans of America (UKA), the White Knights are very secretive about their group.

The United Klans of America Inc. (UKA), based in Alabama, is a Ku Klux Klan organization active in the United States. Led by Robert Shelton, the UKA peaked in membership in the late 1960s and 1970s, and it was the most violent Klan organization of its time. Its headquarters was the Anglo-Saxon Club outside Tuscaloosa, Alabama.

The Indiana Klan was the state of Indiana branch of the Ku Klux Klan, a secret society in the United States that organized in 1915 to promote ideas of racial superiority and affect public affairs on issues of Prohibition, education, political corruption, and morality. Like the rest of the KKK, it was strongly white supremacist against African Americans, Chinese Americans, and also Catholics and Jews, whose faiths were commonly associated with Irish, Italian, Balkan, and Slavic immigrants and their descendants. In Indiana, the Klan did not tend to practice overt violence but used intimidation in certain cases, whereas nationally the organization practiced illegal acts against minority ethnic and religious groups.

Although the Ku Klux Klan is most often associated with white supremacy, the revived Klan of the 1920s was also anti-Catholic. In U.S. states such as Maine, which had a very small black population but a burgeoning number of Acadian, French-Canadian and Irish immigrants, the Klan manifested primarily as a Protestant nativist movement directed against the Catholic minority as well as African-Americans. For a period in the mid-1920s, the Klan captured elements of the Maine Republican Party, even helping to elect a governor, Ralph Owen Brewster.

The U.S. Klans, officially, the U.S. Klans, Knights of the Ku Klux Klan, Inc. was the dominant Ku Klux Klan in the late 1950s and early 1960s. The death of its leader in 1960, along with increased factionalism, splits and competition from other groups led to its decline by the mid-to-late 1960s.

Ku Klux Klan (KKK) nomenclature has evolved over the order's nearly 160 years of existence. The titles and designations were first laid out in the 1920s Kloran, setting out KKK terms and traditions. Like many KKK terms, this is a portmanteau term, formed from Klan and Koran.

The National Knights of the Ku Klux Klan is a Klan faction that has been in existence since November 1963. In the sixties, the National Knights were the main competitors against Robert Shelton's United Klans of America.

The Association of Georgia Klans, also known as the Associated Klans of Georgia, was a Klan faction organized by Samuel Green in 1944, and led by him until his death in 1949. At its height the organization had klaverns in each of Georgia's 159 counties, as well as klaverns in Alabama, Tennessee, South Carolina and Florida. It also had connections with klaverns and kleagles in Ohio and Indiana. After Green's death, however, the organization foundered as it split into different factions, was hit with a tax lien and was beset by adverse publicity. It was moribund by the time of the Supreme Court's "Black Monday" ruling in 1954. A second Association of Georgia Klans was formed when Charles Maddox led dissatisfied members out of the U.S. Klans in 1960. This group appears to have folded into James Venable's National Knights of the Ku Klux Klan by 1965. There is also a current Klan group by that name.

The Canadian branch of the Ku Klux Klan was an expansion of the second Ku Klux Klan established in the United States in 1915. It operated as a fraternity, with chapters established in parts of Canada throughout the 1920s and early 1930s. The first registered provincial chapter was registered in Toronto in 1925 by two Americans and a Canadian. The organization was most successful in Saskatchewan, where it briefly influenced political activity and where its membership included a member of Parliament, Walter Davy Cowan.

Jim Williams was an African-American soldier and militia leader in the 1860s and 1870s in York County, South Carolina. He escaped slavery during the US Civil War and joined the Union Army. After the war, Williams led a black militia organization which sought to protect black rights in the area. In 1871, he was lynched and hung by members of the local Ku Klux Klan. As a result, a large group of local blacks immigrated to Liberia, West Africa.