Related Research Articles

Transphobia consists of negative attitudes, feelings, or actions towards transgender people or transness in general. Transphobia can include fear, aversion, hatred, violence or anger towards people who do not conform to social gender roles. Transphobia is a type of prejudice and discrimination, similar to racism, sexism, or ableism, and it is closely associated with homophobia. People of color who are transgender experience discrimination above and beyond that which can be explained as a simple combination of transphobia and racism.

Gay bashing is an attack, abuse, or assault committed against a person who is perceived by the aggressor to be gay, lesbian, bisexual, transgender or queer (LGBTQ+). It includes both violence against LGBT people and LGBT bullying. The term covers violence against and bullying of people who are LGBT, as well as non-LGBT people whom the attacker perceives to be LGBT.

The field of psychology has extensively studied homosexuality as a human sexual orientation. The American Psychiatric Association listed homosexuality in the DSM-I in 1952 as a "sociopathic personality disturbance," but that classification came under scrutiny in research funded by the National Institute of Mental Health. That research and subsequent studies consistently failed to produce any empirical or scientific basis for regarding homosexuality as anything other than a natural and normal sexual orientation that is a healthy and positive expression of human sexuality. As a result of this scientific research, the American Psychiatric Association removed homosexuality from the DSM-II in 1973. Upon a thorough review of the scientific data, the American Psychological Association followed in 1975 and also called on all mental health professionals to take the lead in "removing the stigma of mental illness that has long been associated" with homosexuality. In 1993, the National Association of Social Workers adopted the same position as the American Psychiatric Association and the American Psychological Association, in recognition of scientific evidence. The World Health Organization, which listed homosexuality in the ICD-9 in 1977, removed homosexuality from the ICD-10 which was endorsed by the 43rd World Health Assembly on 17 May 1990.

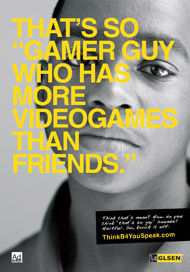

GLSEN is an American education organization working to end discrimination, harassment, and bullying based on sexual orientation, gender identity and gender expression and to prompt LGBT cultural inclusion and awareness in K-12 schools. Founded in 1990 in Boston, Massachusetts, the organization is now headquartered in New York City and has an office of public policy based in Washington, D.C.

LGBTQ culture is a culture shared by lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer individuals. It is sometimes referred to as queer culture, LGBT culture, and LGBTQIA culture, while the term gay culture may be used to mean either "LGBT culture" or homosexual culture specifically.

The questioning of one's sexual orientation, sexual identity, gender, or all three is a process of exploration by people who may be unsure, still exploring, or concerned about applying a social label to themselves for various reasons. The letter "Q" is sometimes added to the end of the acronym LGBT ; the "Q" can refer to either queer or questioning.

Youth suicide is when a young person, generally categorized as someone below the legal age of majority, deliberately ends their own life. Rates of youth suicide and attempted youth suicide in Western societies and other countries are high. Among youth, attempting suicide is more common among girls; however, boys are more likely to actually perform suicide. For example, in Australia suicide is second only to motor vehicle accidents as its leading cause of death for people aged 15 to 25.

Timeline of events related to sexual orientation and medicine

The Think Before You Speak campaign is a television, radio, and magazine advertising campaign launched in 2008 and developed to raise awareness of the common use of derogatory vocabulary among youth towards lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer/questioning (LGBTQ) people. It also aims to "raise awareness about the prevalence and consequences of anti-LGBTQ bias and behaviour in America's schools." As LGBTQ people have become more accepted in the mainstream culture, more studies have confirmed that they are one of the most targeted groups for harassment and bullying. An "analysis of 14 years of hate crime data" by the FBI found that gays and lesbians, or those perceived to be gay, "are far more likely to be victims of a violent hate crime than any other minority group in the United States". "As Americans become more accepting of LGBT people, the most extreme elements of the anti-gay movement are digging in their heels and continuing to defame gays and lesbians with falsehoods that grow more incendiary by the day," said Mark Potok, editor of the Intelligence Report. "The leaders of this movement may deny it, but it seems clear that their demonization of gays and lesbians plays a role in fomenting the violence, hatred and bullying we're seeing." Because of their sexual orientation or gender identity/expression, nearly half of LGBTQ students have been physically assaulted at school. The campaign takes positive steps to counteract hateful and anti-gay speech that LGBTQ students experience in their daily lives in hopes to de-escalate the cycle of hate speech/harassment/bullying/physical threats and violence.

Various issues in medicine relate to lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender people. According to the US Gay and Lesbian Medical Association (GLMA), besides HIV/AIDS, issues related to LGBT health include breast and cervical cancer, hepatitis, mental health, substance use disorders, alcohol use, tobacco use, depression, access to care for transgender persons, issues surrounding marriage and family recognition, conversion therapy, refusal clause legislation, and laws that are intended to "immunize health care professionals from liability for discriminating against persons of whom they disapprove."

Research has found that attempted suicide rates and suicidal ideation among lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBTQ) youth are significantly higher than among the general population.

LGBT sex education is a sex education program within a school, university, or community center that addresses the sexual health needs of LGBT people.

Transgender youth are children or adolescents who do not identify with the sex they were assigned at birth. Because transgender youth are usually dependent on their parents for care, shelter, financial support, and other needs, they face different challenges compared to adults. According to the World Professional Association for Transgender Health, the American Psychological Association, and the American Academy of Pediatrics, appropriate care for transgender youth may include supportive mental health care, social transition, and/or puberty blockers, which delay puberty and the development of secondary sex characteristics to allow children more time to explore their gender identity.

Bullying and suicide are considered together when the cause of suicide is attributable to the victim having been bullied, either in person or via social media. Writers Neil Marr and Tim Field wrote about it in their 2001 book Bullycide: Death at Playtime.

Research shows that a disproportionate number of homeless youth in the United States identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual or transgender, or LGBT. Researchers suggest that this is primarily a result of hostility or abuse from the young people's families leading to eviction or running away. In addition, LGBT youth are often at greater risk for certain dangers while homeless, including being the victims of crime, risky sexual behavior, substance use disorders, and mental health concerns.

The following outline offers an overview and guide to LGBTQ topics:

LGBTQ psychology is a field of psychology of surrounding the lives of LGBTQ+ individuals, in the particular the diverse range of psychological perspectives and experiences of these individuals. It covers different aspects such as identity development including the coming out process, parenting and family practices and support for LGBTQ+ individuals, as well as issues of prejudice and discrimination involving the LGBTQ community.

The health access and health vulnerabilities experienced by the lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer or questioning, intersex, asexual (LGBTQIA) community in South Korea are influenced by the state's continuous failure to pass anti-discrimination laws that prohibit discrimination based on sexual orientation and gender identity. The construction and reinforcement of the South Korean national subject, "kungmin," and the basis of Confucianism and Christian churches perpetuates heteronormativity, homophobia, discrimination, and harassment towards the LGBTQI community. The minority stress model can be used to explain the consequences of daily social stressors, like prejudice and discrimination, that sexual minorities face that result in a hostile social environment. Exposure to a hostile environment can lead to health disparities within the LGBTQI community, like higher rates of depression, suicide, suicide ideation, and health risk behavior. Korean public opinion and acceptance of the LGBTQI community have improved over the past two decades, but change has been slow, considering the increased opposition from Christian activist groups. In South Korea, obstacles to LGBTQI healthcare are characterized by discrimination, a lack of medical professionals and medical facilities trained to care for LGBTQI individuals, a lack of legal protection and regulation from governmental entities, and the lack of medical care coverage to provide for the health care needs of LGBTQI individuals. The presence of Korean LGBTQI organizations is a response to the lack of access to healthcare and human rights protection in South Korea. It is also important to note that research that focuses on Korean LGBTQI health access and vulnerabilities is limited in quantity and quality as pushback from the public and government continues.

"Suicidal ideation" or suicidal thoughts are the precursors of suicide, which is the leading cause of death among youth. Ideation or suicidal thoughts are categorized as: considering, seriously considering, planning, or attempting suicide and youth is typically categorized as individuals below the age of 25. Various research studies show an increased likelihood of suicide ideation in youth in the LGBT community.

People who are LGBT are significantly more likely than those who are not to experience depression, PTSD, and generalized anxiety disorder.

References

- 1 2 3 "LGBTQ". National Alliance on Mental Health.

- 1 2 Russell ST, Fish JN (March 2016). "Mental Health in Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender (LGBT) Youth". Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 12: 465–87. doi:10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-021815-093153. PMC 4887282 . PMID 26772206.

- 1 2 Kann L, Olsen EO, McManus T, Harris WA, Shanklin SL, Flint KH, Queen B, Lowry R, Chyen D, Whittle L, Thornton J, Lim C, Yamakawa Y, Brener N, Zaza S (August 2016). "Sexual Identity, Sex of Sexual Contacts, and Health-Related Behaviors Among Students in Grades 9-12 - United States and Selected Sites, 2015". MMWR. Surveillance Summaries. 65 (9): 1–202. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.ss6509a1 . PMID 27513843.

- 1 2 "LGBT Youth | Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Health | CDC". www.cdc.gov. 2018-11-19. Retrieved 2020-10-26.

- 1 2 "LGBT Youth: Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Health". www.cdc.gov. Centers for Disease Control. 2018-02-06. Retrieved 2018-04-06.

- 1 2 3 4 Human Rights Campaign. "Growing Up LGBT in America: View and Share Statistics". Human Rights Campaign. Retrieved 2018-04-06.

- 1 2 Cahill, Sean; Grasso, Chris; Keuroghlian, Alex; Sciortino, Carl; Mayer, Kenneth (September 2020). "Sexual and Gender Minority Health in the COVID-19 Pandemic: Why Data Collection and Combatting Discrimination Matter Now More Than Ever". American Journal of Public Health. 110 (9): 1360–1361. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2020.305829. ISSN 0090-0036. PMC 7427229 . PMID 32783729.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Whittington C, Hadfield K, & Calderon C (2020). The lives and livelihoods of many in the LGBTQ community are at risk amidst COVID-19 crisis. Retrieved from https://www.hrc.org/resources/the-lives-and-livelihoods-of-many-in-the-lgbtq-community-are-at-risk-amidst

- ↑ Heslin, Kevin C. (2021). "Sexual Orientation Disparities in Risk Factors for Adverse COVID-19–Related Outcomes, by Race/Ethnicity — Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, United States, 2017–2019". MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 70 (5): 149–154. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm7005a1. ISSN 0149-2195. PMC 7861482 . PMID 33539330.

- ↑ Rosario M, & Schrimshaw EW (2013). The sexual identity development and health of lesbian, gay, and bisexual adolescents: An ecological perspective. In Patterson CJ & D’Augelli AR (Eds.), Handbook of psychology and sexual orientation (pp. 87–101). New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

- ↑ Ryan, Caitlin; Huebner, David; Diaz, Rafael M.; Sanchez, Jorge (2009). "Family Rejection as a Predictor of Negative Health Outcomes in White and Latino Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual Young Adults". Pediatrics. 123 (1): 346–352. doi:10.1542/peds.2007-3524. PMID 19117902. S2CID 33361972 . Retrieved 2023-12-06.

- 1 2 Green A, Price-Feeney M, & Dorison S (2020). Implications of COVID-19 for LGBTQ youth mental health and suicide prevention. Retrieved from https://www.thetrevorproject.org/2020/04/03/implications-of-covid-19-for-lgbtq-youth-mental-health-and-suicide-prevention/

- ↑ Ali MM, West K, Teich JL, Lynch S, Mutter R, & Dubenitz J (2019). Utilization of mental health services in educational setting by adolescents in the United States. The Journal of School Health, 89, 393–401. 10.1111/josh.12753

- ↑ Golberstein E, Wen H, & Miller BF (2020). Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) and mental health for children and adolescents. Journal of the American Medical Association Pediatrics. Advance online publication. 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.1456

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Sandoval, Jonathan, ed. (2013-02-25). Crisis Counseling, Intervention and Prevention in the Schools (3 ed.). New York: Routledge. doi:10.4324/9780203145852. ISBN 978-0-203-14585-2.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Marszalek, John F.; Logan, Collen R. (2014). ""It Takes a Village": Advocating for Sexual Minority Youth". In Capuzzi, David; Gross, Douglas R. (eds.). Youth at risk: a prevention resource for counselors, teachers, and parents. American Counseling Association (Sixth ed.). Wiley.

- ↑ Reisner, Sari L.; Vetters, Ralph; Leclerc, M.; Zaslow, Shayne; Wolfrum, Sarah; Shumer, Daniel; Mimiaga, Matthew J. (March 2015). "Mental Health of Transgender Youth in Care at an Adolescent Urban Community Health Center: A Matched Retrospective Cohort Study". Journal of Adolescent Health. 56 (3): 274–279. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2014.10.264. PMC 4339405 . PMID 25577670.

- 1 2 3 Veale, Jaimie F.; Watson, Ryan J.; Peter, Tracey; Saewyc, Elizabeth M. (January 2017). "Mental Health Disparities Among Canadian Transgender Youth". Journal of Adolescent Health. 60 (1): 44–49. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2016.09.014. ISSN 1054-139X. PMC 5630273 . PMID 28007056.

- 1 2 3 Cianciotto, Jason (2012). LGBT youth in America's schools. Sean Cahill. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. ISBN 978-0-472-02832-0. OCLC 793947628.

- 1 2 de Vries AL, Steensma TD, Doreleijers TA, Cohen-Kettenis PT. 2011. Puberty suppression in adolescents with gender identity disorder: a prospective follow-up study. J. Sex. Med. 8:2276–83

- ↑ Green AE, DeChants JP, Price MN, Davis CK. 2022. Association of gender-affirming hormone therapy with depression, thoughts of suicide, and attempted suicide among transgender and nonbinary youth. J. Adolesc. Health 70:643–49

- ↑ Turban JL, King D, Carswell JM, Keuroghlian AS. 2020. Pubertal suppression for transgender youth and risk of suicidal ideation. Pediatrics 145:e20191725

- ↑ Cover R (2012). Queer Youth Suicide, Culture and Identity: Unliveable Lives?. Burlington: Ashgate Publishing Limited. pp. 57–75. ISBN 978-1-4094-4447-3.

- 1 2 "National Coming Out Day Youth Report". issuu. 5 October 2012. Retrieved 2018-04-07.

- ↑ Heath, Terrance (2018-10-18). "Here's your complete list of LGBTQ holidays & commemorations". LGBTQ Nation. Retrieved 2020-10-26.

- ↑ "Celebrating LGBTQ+ history this month". UTRGV. 2020-10-13. Retrieved 2020-10-26.