Related Research Articles

In criminology, the broken windows theory states that visible signs of crime, antisocial behavior and civil disorder create an urban environment that encourages further crime and disorder, including serious crimes. The theory suggests that policing methods that target minor crimes, such as vandalism, loitering, public drinking and fare evasion, help to create an atmosphere of order and lawfulness.

Ultraviolet (UV) spectroscopy or ultraviolet–visible (UV–VIS) spectrophotometry refers to absorption spectroscopy or reflectance spectroscopy in part of the ultraviolet and the full, adjacent visible regions of the electromagnetic spectrum. Being relatively inexpensive and easily implemented, this methodology is widely used in diverse applied and fundamental applications. The only requirement is that the sample absorb in the UV-Vis region, i.e. be a chromophore. Absorption spectroscopy is complementary to fluorescence spectroscopy. Parameters of interest, besides the wavelength of measurement, are absorbance (A) or transmittance (%T) or reflectance (%R), and its change with time.

Spectrophotometry is a branch of electromagnetic spectroscopy concerned with the quantitative measurement of the reflection or transmission properties of a material as a function of wavelength. Spectrophotometry uses photometers, known as spectrophotometers, that can measure the intensity of a light beam at different wavelengths. Although spectrophotometry is most commonly applied to ultraviolet, visible, and infrared radiation, modern spectrophotometers can interrogate wide swaths of the electromagnetic spectrum, including x-ray, ultraviolet, visible, infrared, and/or microwave wavelengths.

In the United States, the relationship between race and crime has been a topic of public controversy and scholarly debate for more than a century. Crime rates vary significantly between racial groups; however, academic research indicates that the over-representation of some racial minorities in the criminal justice system can in part be explained by socioeconomic factors, such as poverty, exposure to poor neighborhoods, poor access to public and early education, and exposure to harmful chemicals and pollution. Racial housing segregation has also been linked to racial disparities in crime rates, as black Americans have historically and to the present been prevented from moving into prosperous low-crime areas through actions of the government and private actors. Various explanations within criminology have been proposed for racial disparities in crime rates, including conflict theory, strain theory, general strain theory, social disorganization theory, macrostructural opportunity theory, social control theory, and subcultural theory.

Michael D. Maltz is an American electrical engineer, criminologist and Emeritus Professor at University of Illinois at Chicago in criminal justice, and adjunct professor and researcher at Ohio State University.

Operation Ceasefire (also known as the Boston Gun Project and the Boston Miracle) is a problem-oriented policing initiative implemented in 1996 in Boston, Massachusetts. The program was specifically aimed at youth gun violence as a large-scale problem. The plan is based on the work of criminologist David M. Kennedy.

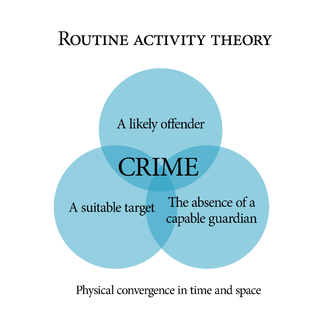

Routine activity theory is a sub-field of crime opportunity theory that focuses on situations of crimes. It was first proposed by Marcus Felson and Lawrence E. Cohen in their explanation of crime rate changes in the United States between 1947 and 1974. The theory has been extensively applied and has become one of the most cited theories in criminology. Unlike criminological theories of criminality, routine activity theory studies crime as an event, closely relates crime to its environment and emphasizes its ecological process, thereby diverting academic attention away from mere offenders.

In United States criminal procedure terminology, a process crime is an offense against the judicial process. These crimes include failure to appear, false statements, obstruction of justice, contempt of court and perjury.

Ronald Weitzer is an American sociologist specializing in criminology and a professor at George Washington University, known for his publications on police-minority relations and on the sex industry.

Pre-crime is the idea that the occurrence of a crime can be anticipated before it happens. The term was coined by science fiction author Philip K. Dick, and is increasingly used in academic literature to describe and criticise the tendency in criminal justice systems to focus on crimes not yet committed. Precrime intervenes to punish, disrupt, incapacitate or restrict those deemed to embody future crime threats. The term precrime embodies a temporal paradox, suggesting both that a crime has not yet occurred and that it is a foregone conclusion.

Lawrence W. Sherman is an experimental criminologist and police educator who is the founder of evidence-based policing. Since 2022 he has served as Chief Scientific Officer of the Metropolitan Police at Scotland Yard, as well as Wolfson Professor of Criminology Emeritus at the University of Cambridge Institute of Criminology Wolfson Professor of Criminology.

The self-control theory of crime, often referred to as the general theory of crime, is a criminological theory about the lack of individual self-control as the main factor behind criminal behavior. The self-control theory of crime suggests that individuals who were ineffectually parented before the age of ten develop less self-control than individuals of approximately the same age who were raised with better parenting. Research has also found that low levels of self-control are correlated with criminal and impulsive conduct.

Criminology is the interdisciplinary study of crime and deviant behaviour. Criminology is a multidisciplinary field in both the behavioural and social sciences, which draws primarily upon the research of sociologists, political scientists, economists, legal sociologists, psychologists, philosophers, psychiatrists, social workers, biologists, social anthropologists, scholars of law and jurisprudence, as well as the processes that define administration of justice and the criminal justice system.

The stop-question-and-frisk program, or stop-and-frisk, in New York City, is a New York City Police Department (NYPD) practice of temporarily detaining, questioning, and at times searching civilians and suspects on the street for weapons and other contraband. This is what is known in other places in the United States as the Terry stop. The rules for the policy are contained in the state's criminal procedure law section 140.50 and based on the decision of the US Supreme Court in the case of Terry v. Ohio.

David L. Weisburd, is an Israeli/American criminologist who is well known for his research on crime and place, policing and white collar crime. Weisburd was the 2010 recipient of the prestigious Stockholm Prize in Criminology, and was awarded the Israel Prize in Social Work and Criminological Research in 2015, considered the state's highest honor. Weisburd is Distinguished Professor of Criminology, Law and Society at George Mason University. and Walter E. Meyer Professor Emeritus of Law and Criminal Justice in the Institute of Criminology of the Hebrew University Faculty of Law. At George Mason University, Weisburd was founder of the Center for Evidence-Based Crime Policy and is now its Executive Director. Weisburd also serves as Chief Science Advisor at the National Policing Institute in Washington, D.C. Weisburd was the founding editor of the Journal of Experimental Criminology, and is editor of the Cambridge Elements in Criminology Series.

Crime displacement is the relocation of crime as a result of police crime-prevention efforts. Crime displacement has been linked to problem-oriented policing, but it may occur at other levels and for other reasons. Community-development efforts may be a reason why criminals move to other areas for their criminal activity. The idea behind displacement is that when motivated criminal offenders are deterred, they will commit crimes elsewhere. Geographic police initiatives include assigning police officers to specific districts so they become familiar with residents and their problems, creating a bond between law-enforcement agencies and the community. These initiatives complement crime displacement, and are a form of crime prevention. Experts in the area of crime displacement include Kate Bowers, Rob T. Guerette, and John E. Eck.

A Crime concentration is a spatial area to which high levels of crime incidents are attributed. A crime concentration can be the result of homogeneous or heterogeneous crime incidents. Hotspots are the result of various crimes occurring in relative proximity to each other within predefined human geopolitical or social boundaries. Crime concentrations are smaller units or set of crime targets within a hotspot. A single or a conjunction of crime concentrations within a study area can make up a crime hotspot.

Anthony Allan Braga is an American criminologist and the Jerry Lee Professor of Criminology at the University of Pennsylvania. Braga is also the Director of the Crime and Justice Policy Lab at the University of Pennsylvania. He previously held faculty and senior research positions at Harvard University, Northeastern University, Rutgers University, and the University of California at Berkeley. Braga is a member of the federal monitor team overseeing the reforms to New York City Police Department (NYPD) policies, training, supervision, auditing, and handling of complaints and discipline regarding stops and frisks and trespass enforcement.

In criminal justice, the liberation hypothesis proposes that extra-legal factors affect sentencing outcomes more in regards to less serious offenses compared to more serious ones, ostensibly because juries and judges will feel less able to follow their personal sentiments with regard to more serious crimes. The hypothesis also proposes that the extent to which extra-legal factors sentencing outcomes is dependent on the strength of the evidence in the case. The hypothesis was first proposed by Harry Kalven and Hans Zeisel in their 1966 book "The American Jury". Since then, multiple studies have found support for it.

Experimental criminology is a field within criminology that uses scientific experiments to answer questions about crime: its prevention, punishment and harm. These experiments are primarily conducted in real-life settings, rather than in laboratories. From policing to prosecution to probation, prisons and parole, these field experiments compare similar units with different practices for dealing with crime and responses to crime. These units can be individual suspects or offenders, people, places, neighborhoods, times of day, gangs, or even police officers or judges. The experiments often use random assignment to create similar units in both a "treatment" and a "control" group, with the "control" sometimes consisting of the current way of dealing with crime and the "treatment" a new way of doing so. Such experiments, while not perfect, are generally considered to be the best available way to estimate the cause and effect relationship of one variable to another. Other research designs not using random assignment are also considered to be experiments because they entail human manipulation of the causal relationships being tested.

References

- 1 2 3 Weisburd, David (2015). "The Law of Crime Concentration and the Criminology of Place". Criminology. 53 (2): 133–157. doi:10.1111/1745-9125.12070.

- ↑ Sherman, Lawrence; Patrick Gartin; Michael Buerger (1989). "Hot spots of predatory crime: Routine activities and the criminology of place". Criminology. 27 (1): 27–56. doi:10.1111/j.1745-9125.1989.tb00862.x.

- 1 2 Weisburd, David; Elizabeth Groff; Sue-ming Yang (2012). The Criminology of Place: Street Segments And Our Understanding of the Crime Problem. Oxford University Press.

- ↑ Weisburd, David; Shai Amram (2014). "The law of concentrations of crime at place: The case of Tel Aviv-Jaffa". Police Practice & Research. 15 (2): 101–114. doi:10.1080/15614263.2013.874169.

- ↑ Lee, YongJei; John E. Eck; SooHyun O; Natalie N. Martinez (2017). "How concentrated is crime at places? A systematic review from 1970 to 2015". Crime Science. 6 (6): 1–16. doi: 10.1186/s40163-017-0069-x .

- ↑ Schnell, Cory; Anthony A. Braga; Eric L. Piza (2017). "The Influence of Community Areas, Neighborhood Clusters, and Street Segments on the Spatial Variability of Violent Crime in Chicago". Journal of Quantitative Criminology. 33: 469–496. doi:10.1007/s10940-015-9276-3.

- 1 2 Haberman, Cory P.; Evan T. Song; Jerry H. Ratfliffe (2017). "Assessing the Validity of the Law of Crime Concentration Across Different Temporal Scales". Journal of Quantitative Criminology. 33 (3): 547–567. doi:10.1007/s10940-016-9327-4.

- 1 2 Gill, Charlotte; Alese Wooditch; David Weisburd (2017). "Testing the "Law of Crime Concentration at Place" in a Suburban Setting: Implications for Research and Practice". Journal of Quantitative Criminology. 33 (3): 519–545. doi:10.1007/s10940-016-9304-y.