In the history of cryptography, the "System 97 Typewriter for European Characters" or "Type B Cipher Machine", codenamed Purple by the United States, was an encryption machine used by the Japanese Foreign Office from February 1939 to the end of World War II. The machine was an electromechanical device that used stepping-switches to encrypt the most sensitive diplomatic traffic. All messages were written in the 26-letter English alphabet, which was commonly used for telegraphy. Any Japanese text had to be transliterated or coded. The 26-letters were separated using a plug board into two groups, of six and twenty letters respectively. The letters in the sixes group were scrambled using a 6 × 25 substitution table, while letters in the twenties group were more thoroughly scrambled using three successive 20 × 25 substitution tables.

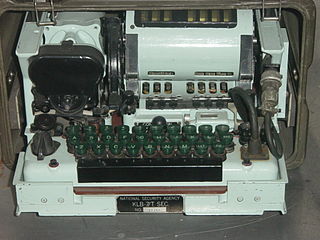

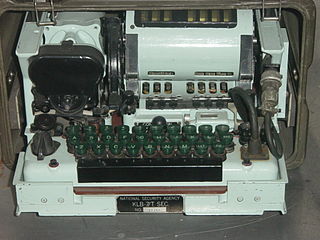

In the history of cryptography, the ECM Mark II was a cipher machine used by the United States for message encryption from World War II until the 1950s. The machine was also known as the SIGABA or Converter M-134 by the Army, or CSP-888/889 by the Navy, and a modified Navy version was termed the CSP-2900.

William Frederick Friedman was a US Army cryptographer who ran the research division of the Army's Signal Intelligence Service (SIS) in the 1930s, and parts of its follow-on services into the 1950s. In 1940, subordinates of his led by Frank Rowlett broke Japan's PURPLE cipher, thus disclosing Japanese diplomatic secrets before America's entrance into World War II.

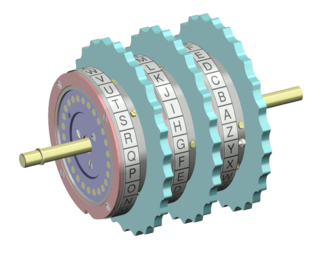

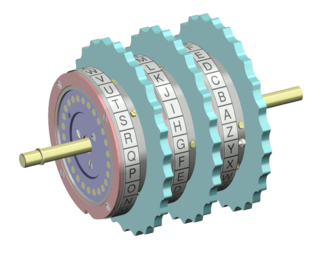

In cryptography, a rotor machine is an electro-mechanical stream cipher device used for encrypting and decrypting messages. Rotor machines were the cryptographic state-of-the-art for much of the 20th century; they were in widespread use in the 1920s–1970s. The most famous example is the German Enigma machine, the output of which was deciphered by the Allies during World War II, producing intelligence code-named Ultra.

Arlington Hall is a historic building in Arlington, Virginia, originally a girls' school and later the headquarters of the United States Army's Signal Intelligence Service (SIS) cryptography effort during World War II. The site presently houses the George P. Shultz National Foreign Affairs Training Center, and the Army National Guard's Herbert R. Temple, Jr. Readiness Center. It is located on Arlington Boulevard between S. Glebe Road and S. George Mason Drive.

Elizebeth Smith Friedman was an American cryptanalyst and author who deciphered enemy codes in both World Wars and helped to solve international smuggling cases during Prohibition. Over the course of her career, she worked for the United States Treasury, Coast Guard, Navy and Army, and the International Monetary Fund. She has been called "America's first female cryptanalyst".

Frank Byron Rowlett was an American cryptologist.

Abraham Sinkov was a US cryptanalyst. An early employee of the U.S. Army's Signals Intelligence Service, he held several leadership positions during World War II, transitioning to the new National Security Agency after the war, where he became a deputy director. After retiring in 1962, he taught mathematics at Arizona State University.

Solomon Kullback was an American cryptanalyst and mathematician, who was one of the first three employees hired by William F. Friedman at the US Army's Signal Intelligence Service (SIS) in the 1930s, along with Frank Rowlett and Abraham Sinkov. He went on to a long and distinguished career at SIS and its eventual successor, the National Security Agency (NSA). Kullback was the Chief Scientist at the NSA until his retirement in 1962, whereupon he took a position at the George Washington University.

Cryptography, the use of codes and ciphers to protect secrets, began thousands of years ago. Until recent decades, it has been the story of what might be called classical cryptography — that is, of methods of encryption that use pen and paper, or perhaps simple mechanical aids. In the early 20th century, the invention of complex mechanical and electromechanical machines, such as the Enigma rotor machine, provided more sophisticated and efficient means of encryption; and the subsequent introduction of electronics and computing has allowed elaborate schemes of still greater complexity, most of which are entirely unsuited to pen and paper.

Cryptography was used extensively during World War II because of the importance of radio communication and the ease of radio interception. The nations involved fielded a plethora of code and cipher systems, many of the latter using rotor machines. As a result, the theoretical and practical aspects of cryptanalysis, or codebreaking, were much advanced.

The TSEC/KL-7, also known as Adonis was an off-line non-reciprocal rotor encryption machine. The KL-7 had rotors to encrypt the text, most of which moved in a complex pattern, controlled by notched rings. The non-moving rotor was fourth from the left of the stack. The KL-7 also encrypted the message indicator.

The Signal Intelligence Service (SIS) was the United States Army codebreaking division through World War II. It was founded in 1930 to compile codes for the Army. It was renamed the Signal Security Agency in 1943, and in September 1945, became the Army Security Agency. For most of the war it was headquartered at Arlington Hall, on Arlington Boulevard in Arlington, Virginia, across the Potomac River from Washington (D.C.). During World War II, it became known as the Army Security Agency, and its resources were reassigned to the newly established National Security Agency (NSA).

SIGCUM, also known as Converter M-228, was a rotor cipher machine used to encrypt teleprinter traffic by the United States Army. Hastily designed by William Friedman and Frank Rowlett, the system was put into service in January 1943 before any rigorous analysis of its security had taken place. SIGCUM was subsequently discovered to be insecure by Rowlett, and was immediately withdrawn from service. The machine was redesigned to improve its security, reintroduced into service by April 1943, and remained in use until the 1960s.

In the history of cryptography, 91-shiki ōbun injiki or Angōki Taipu-A, codenamed Red by the United States, was a diplomatic cryptographic machine used by the Japanese Foreign Office before and during World War II. A relatively simple device, it was quickly broken by western cryptographers. The Red cipher was succeeded by the Type B "Purple" machine which used some of the same principles. Parallel usage of the two systems assisted in the breaking of the Purple system.

Genevieve Marie Grotjan Feinstein was an American mathematician and cryptanalyst. She worked for the Signals Intelligence Service throughout World War II, during which time she played an important role in deciphering the Japanese cryptography machine Purple, and later worked on the Cold War-era Venona project.

Japanese army and diplomatic codes. This article is on Japanese army and diplomatic ciphers and codes used up to and during World War II, to supplement the article on Japanese naval codes. The diplomatic codes were significant militarily, particularly those from diplomats in Germany.

Wilma Zimmerman Davis was an early American codebreaker during World War II. She was a leading national cryptanalyst before and during World War II and the Vietnam War. She graduated with a degree in Mathematics from Bethany College and successfully completed navy correspondence course in cryptology. She began her career as a leading cryptanalyst which spanned over 30 years in the United States Army Signal Intelligence Service (SIS), a predecessor of the National Security Agency (NSA) in the 1930s. She was hired by William Friedman, who was a US cryptographer in the Army and led the research division of the Army’s Signal Intelligence in the 1930s. Wilma Davis worked as a cryptanalyst on the Italian, Japanese, Chinese, Vietnamese, and Russian problems. She also worked on the VENONA project.

SIGTOT was a one-time tape machine for encrypting teleprinter communication that was used by the United States during World War II and after for the most sensitive message traffic. It was developed after security flaws were discovered in an earlier rotor machine for the same purpose, called SIGCUM. SIGTOT was designed by Leo Rosen and used the same Bell Telephone 132B2 mixer as SIGCUM. The British developed a similar machine called the 5-UCO. Later an improved mixer, the SSM-33, replaced the 131B2,