Lydia was an Iron Age kingdom situated in the west of Asia Minor, in modern-day Turkey. Later, it became an important province of the Achaemenid Empire and then the Roman Empire. Its capital was Sardis.

The Scythians or Scyths in composition) and sometimes also referred to as the Pontic Scythians, were an ancient Eastern Iranic equestrian nomadic people who had migrated during the 9th to 8th centuries BC from Central Asia to the Pontic Steppe in modern-day Ukraine and Southern Russia, where they remained established from the 7th century BC until the 3rd century BC.

Mopsus was the name of one of two famous seers in Greek mythology; his rival being Calchas. A historical or legendary Mopsos or Mukšuš may have been the founder of a house in power at widespread sites in the coastal plains of Pamphylia and Cilicia during the early Iron Age.

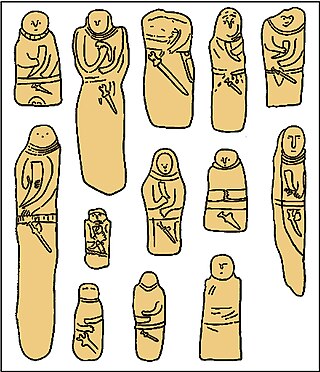

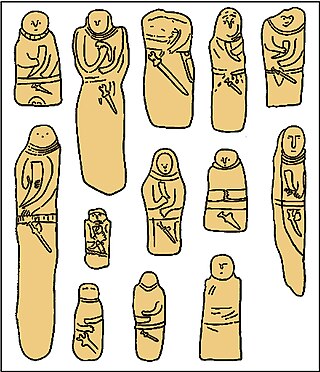

A kurgan is a type of tumulus constructed over a grave, often characterized by containing a single human body along with grave vessels, weapons, and horses. Originally in use on the Pontic–Caspian steppe, kurgans spread into much of Central Asia and Eastern, Southeast, Western, and Northern Europe during the third millennium BC.

A rhyton is a roughly conical container from which fluids were intended to be drunk or to be poured in some ceremony such as libation, or merely at table; in other words, a cup. A rhyton is typically formed in the shape of either an animal's head or an animal horn; in the latter case it often terminates in the shape of an animal's body. Rhyta were produced over large areas of ancient Eurasia during the Bronze and Iron Ages, especially from Persia to the Balkans.

Pantikapaion was an ancient Greek city on the eastern shore of Crimea, which the Greeks called Taurica. The city lay on the western side of the Cimmerian Bosporus, and was founded by Milesians in the late 7th or early 6th century BC, on a hill later named Mount Mithridat. Its ruins now lie in the modern city of Kerch.

The Gundestrup cauldron is a richly decorated silver vessel, thought to date from between 200 BC and 300 AD, or more narrowly between 150 BC and 1 BC. This places it within the late La Tène period or early Roman Iron Age. The cauldron is the largest known example of European Iron Age silver work. It was found dismantled, with the other pieces stacked inside the base, in 1891, in a peat bog near the hamlet of Gundestrup in the Aars parish of Himmerland, Denmark. It is now usually on display in the National Museum of Denmark in Copenhagen, with replicas at other museums; it was in the UK on a travelling exhibition called The Celts during 2015–2016.

Animal style art is an approach to decoration found from Ordos culture to Northern Europe in the early Iron Age, and the barbarian art of the Migration Period, characterized by its emphasis on animal motifs. The zoomorphic style of decoration was used to decorate small objects by warrior-herdsmen, whose economy was based on breeding and herding animals, supplemented by trade and plunder. Animal art is a more general term for all art depicting animals.

Scytho-Siberian art is the art associated with the cultures of the Scytho-Siberian world, primarily consisting of decorative objects such as jewellery, produced by the nomadic tribes of the Eurasian Steppe, with the western edges of the region vaguely defined by ancient Greeks. The identities of the nomadic peoples of the steppes is often uncertain, and the term "Scythian" should often be taken loosely; the art of nomads much further east than the core Scythian territory exhibits close similarities as well as differences, and terms such as the "Scytho-Siberian world" are often used. Other Eurasian nomad peoples recognised by ancient writers, notably Herodotus, include the Massagetae, Sarmatians, and Saka, the last a name from Persian sources, while ancient Chinese sources speak of the Xiongnu or Hsiung-nu. Modern archaeologists recognise, among others, the Pazyryk, Tagar, and Aldy-Bel cultures, with the furthest east of all, the later Ordos culture a little west of Beijing. The art of these peoples is collectively known as steppes art.

The Ziwiye hoard is a treasure hoard containing gold, silver, and ivory objects, also including a few gold pieces with the shape of a human face, that was uncovered in a plot of land outside Ziwiyeh castle, near the city of Saqqez in Kurdistan Province, Iran, in 1947.

A drinking horn is the horn of a bovid used as a cup. Drinking horns are known from Classical Antiquity, especially the Balkans, and remained in use for ceremonial purposes throughout the Middle Ages and the Early Modern period in some parts of Europe, notably in Germanic Europe, and in the Caucasus. Drinking horns remain an important accessory in the culture of ritual toasting in Georgia in particular, where they are known by the local name of kantsi.

The Thracian religion comprised the mythology, ritual practices and beliefs of the Thracians, a collection of closely related ancient Indo-European peoples who inhabited eastern and southeastern Europe and northwestern Anatolia throughout antiquity and who included the Thracians proper, the Getae, the Dacians, and the Bithynians.

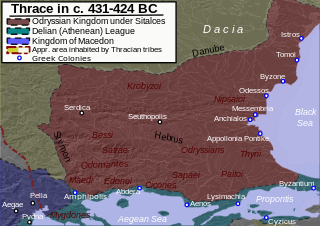

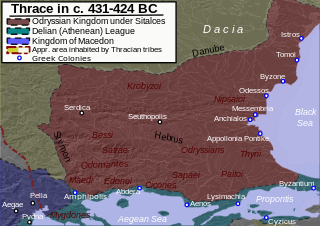

The Thracians were a group of Indo-European tribes inhabiting a large area in Central and Southeastern Europe, centred in modern Bulgaria. They were bordered by the Scythians to the north, the Celts and the Illyrians to the west, the Greeks to the south, and the Black Sea to the east.

The griffin, griffon, or gryphon is a legendary creature with the body, tail, and back legs of a lion, and the head and wings of an eagle with its talons on the front legs.

The Scythian religion refers to the mythology, ritual practices and beliefs of the Scythian cultures, a collection of closely related ancient Iranian peoples who inhabited Central Asia and the Pontic–Caspian steppe in Eastern Europe throughout Classical Antiquity, spoke the Scythian language, and which included the Scythians proper, the Cimmerians, the Sarmatians, the Alans, the Sindi, the Massagetae and the Saka.

Dacian art is the art associated with the peoples known as Dacians or North Thracians; The Dacians created an art style in which the influences of Scythians and the Greeks can be seen. They were highly skilled in gold and silver working and in pottery making. Pottery was white with red decorations in floral, geometric, and stylized animal motifs. Similar decorations were worked in metal, especially the figure of a horse, which was common on Dacian coins.

The Achaemenid Persian Lion Rhyton is a gold rhyton from the Achaemenid Empire, dated to about 500 BC. It is 6.7 inches high and is made in solid gold, with the different parts joined together by soldering, done so skilfully as to leave no obvious marks.

The Scythian culture was an Iron Age archaeological culture which flourished on the Pontic-Caspian steppe in Eastern Europe from about 700 BC to 200 AD. It is associated with the Scythians, Cimmerians, and other peoples inhabiting the region of Scythia, and was part of the wider Scytho-Siberian world.

Artimpasa was a complex androgynous Scythian goddess of fertility who possessed power over sovereignty and the priestly force. Artimpasa was the Scythian variant of the Iranian goddess Arti/Aṣ̌i.

The Snake-Legged Goddess, also referred to as the Anguipede Goddess, was the ancestor-goddess of the Scythians according to the Scythian religion.