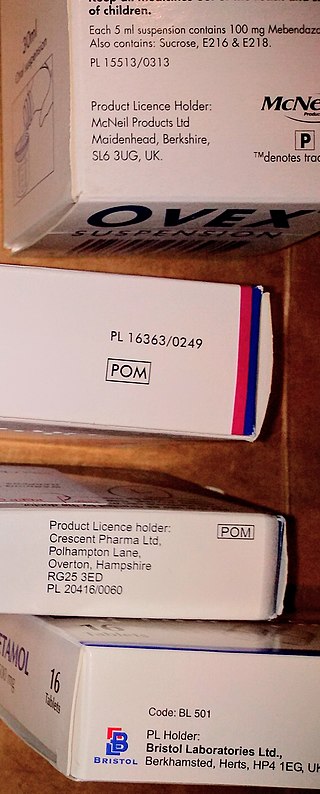

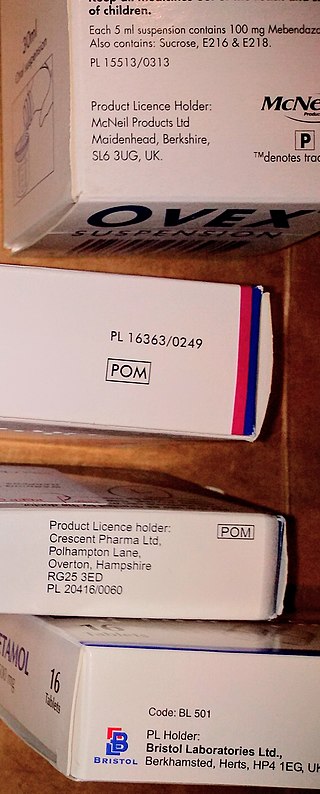

A prescription drug is a pharmaceutical drug that is permitted to be dispensed only to those with a medical prescription. In contrast, over-the-counter drugs can be obtained without a prescription. The reason for this difference in substance control is the potential scope of misuse, from drug abuse to practicing medicine without a license and without sufficient education. Different jurisdictions have different definitions of what constitutes a prescription drug.

General practice is the name given in various nations, such as the United Kingdom, India, Australia, New Zealand and South Africa to the services provided by general practitioners. In some nations, such as the US, similar services may be described as family medicine or primary care. The term Primary Care in the UK may also include services provided by community pharmacy, optometrist, dental surgery and community hearing care providers. The balance of care between primary care and secondary care - which usually refers to hospital based services - varies from place to place, and with time. In many countries there are initiatives to move services out of hospitals into the community, in the expectation that this will save money and be more convenient.

The British Medical Association (BMA) is a registered trade union for doctors in the United Kingdom. It does not regulate or certify doctors, a responsibility which lies with the General Medical Council. The BMA has a range of representative and scientific committees and is recognised by National Health Service (NHS) employers alongside the Hospital Consultants and Specialists Association as one of two national contract negotiators for doctors.

Family medicine is a medical specialty within primary care that provides continuing and comprehensive health care for the individual and family across all ages, genders, diseases, and parts of the body. The specialist, who is usually a primary care physician, is named a family physician. It is often referred to as general practice and a practitioner as a general practitioner. Historically, their role was once performed by any doctor with qualifications from a medical school and who works in the community. However, since the 1950s, family medicine / general practice has become a specialty in its own right, with specific training requirements tailored to each country. The names of the specialty emphasize its holistic nature and/or its roots in the family. It is based on knowledge of the patient in the context of the family and the community, focusing on disease prevention and health promotion. According to the World Organization of Family Doctors (WONCA), the aim of family medicine is "promoting personal, comprehensive and continuing care for the individual in the context of the family and the community". The issues of values underlying this practice are usually known as primary care ethics.

Alan Julian Macbeth Tudor-Hart, commonly known as Julian Tudor Hart, was a general practitioner (GP) who worked in Wales for 30 years, known for theorising the inverse care law. He produced medical research and wrote many books and medical articles.

In the United Kingdom, Ireland, and parts of the Commonwealth, consultant is the title of a senior hospital-based physician or surgeon who has completed all of their specialist training and been placed on the specialist register in their chosen speciality. Their role is entirely distinct from that of a general practitioner.

General medical services (GMS) is the range of healthcare that is provided by general practitioners as part of the National Health Service in the United Kingdom. The NHS specifies what GPs, as independent contractors, are expected to do and provides funding for this work through arrangements known as the General Medical Services Contract. Today, the GMS contract is a UK-wide arrangement with minor differences negotiated by each of the four UK health departments. In 2013 60% of practices had a GMS contract as their principal contract. The contract has sub-sections and not all are compulsory. The other forms of contract are the Personal Medical Services or Alternative Provider Medical Services contracts. They are designed to encourage practices to offer services over and above the standard contract. Alternative Provider Medical Services contracts, unlike the other contracts, can be awarded to anyone, not just GPs, don't specify standard essential services, and are time limited. A new contract is issued each year.

GPASS, General Practice Administration System for Scotland, is a clinical record and practice administration software package that was previously in widespread by Scottish general medical practitioners. It launched in 1984 and became dominant in the market while still being in public ownership, but a loss of confidence in it led to other systems being adopted and it had been largely been replaced by 2012.

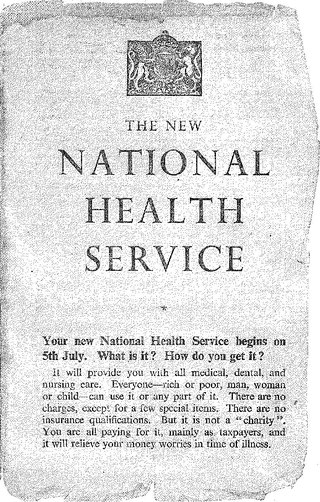

The name National Health Service (NHS) is used to refer to the publicly funded health care services of England, Scotland and Wales, individually or collectively. Northern Ireland's services are known as 'Health and Social Care' to promote its dual integration of health and social services.

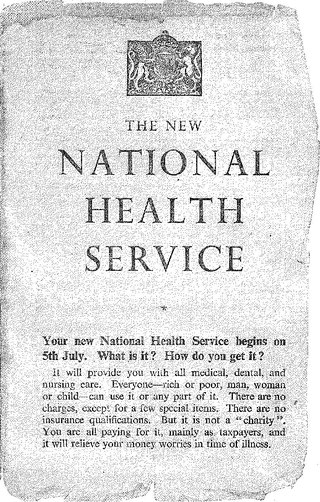

The National Health Service (NHS) is the publicly funded healthcare system in England, and one of the four National Health Service systems in the United Kingdom. It is the second largest single-payer healthcare system in the world after the Brazilian Sistema Único de Saúde. Primarily funded by the government from general taxation, and overseen by the Department of Health and Social Care, the NHS provides healthcare to all legal English residents and residents from other regions of the UK, with most services free at the point of use for most people. The NHS also conducts research through the National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR).

Healthcare in England is mainly provided by the National Health Service (NHS), a public body that provides healthcare to all permanent residents in England, that is free at the point of use. The body is one of four forming the UK National Health Service as health is a devolved matter; there are differences with the provisions for healthcare elsewhere in the United Kingdom, and in England it is overseen by NHS England. Though the public system dominates healthcare provision in England, private health care and a wide variety of alternative and complementary treatments are available for those willing and able to pay.

Homeopathy is fairly common in some countries while being uncommon in others. In some countries, there are no specific legal regulations concerning the use of homeopathy, while in others, licenses or degrees in conventional medicine from accredited universities are required.

The National Health Service in England was created by the National Health Service Act 1946. Responsibility for the NHS in Wales was passed to the Secretary of State for Wales in 1969, leaving the Secretary of State for Social Services responsible for the NHS in England by itself.

Michael Dixon LVO, OBE, FRCGP, FRCP is an English general practitioner and current Head of the Royal Medical Household. He is Chair of The College of Medicine and Integrated Health and Visiting Professor at the University of Westminster.

Michael Alexander Leary Pringle CBE is a British physician and academic. He is the emeritus professor of general practice (GP) at the University of Nottingham, a past president of the Royal College of General Practitioners (RCGP), best known for his primary care research on clinical audit, significant event audit, revalidation, quality improvement programmes and his contributions to health informatics services and health politics. He is a writer of medicine and fiction, with a number of publications including articles, books, chapters, forewords and guidelines.

Family practitioner committees were established by the National Health Service Re-organisation Act 1973. They replaced local executive councils, which had been established in 1948 to manage primary care.

Private healthcare in the UK, where universal state-funded healthcare is provided by the National Health Service, is a niche market.

Epidemiology in Country Practice is a book by William Pickles (1885–1969), a rural general practitioner (GP) physician in Wensleydale, North Yorkshire, England, first published in 1939. The book reports on how careful observations can lead to correlations between transmission of infective disease between families, farms and villages.

In 2005 the National Health Service (NHS) in the United Kingdom began deployment of electronic health record systems in NHS Trusts. The goal was to have all patients with a centralized electronic health record by 2010. Lorenzo patient record systems were adopted in a number of NHS trusts. While many hospitals acquired electronic patient records systems in this process, there was no national healthcare information exchange. Ultimately, the program was dismantled after a cost to the UK taxpayer was over $24 billion, and is considered one of the most expensive healthcare IT failures.

Margaret Mary McCartney is a general practitioner, freelance writer and broadcaster based in Glasgow, Scotland. McCartney is a vocal advocate for evidence-based medicine. McCartney was a regular columnist at the British Medical Journal. She regularly writes articles for The Guardian and currently contributes to the BBC Radio 4 programme, Inside Health. She has written three popular science books, The Patient Paradox, The State of Medicine and Living with Dying. During the COVID-19 pandemic, McCartney contributed content to academic journals and broadcasting platforms, personal blog, and social media to inform the public and dispel myths about coronavirus disease.