Related Research Articles

The Celts or Celtic peoples were a collection of Indo-European peoples in Europe and Anatolia, identified by their use of Celtic languages and other cultural similarities. Major Celtic groups included the Gauls; the Celtiberians and Gallaeci of Iberia; the Britons, Picts, and Gaels of Britain and Ireland; the Boii; and the Galatians. The interrelationships of ethnicity, language and culture in the Celtic world are unclear and debated; for example over the ways in which the Iron Age people of Britain and Ireland should be called Celts. In current scholarship, 'Celt' primarily refers to 'speakers of Celtic languages' rather than to a single ethnic group.

The Picts were a group of peoples in what is now Scotland north of the Firth of Forth, in the Early Middle Ages. Where they lived and details of their culture can be gleaned from early medieval texts and Pictish stones. The name Picti appears in written records as an exonym from the late third century AD. They are assumed to have been descendants of the Caledonii and other northern Iron Age tribes. Their territory is referred to as "Pictland" by modern historians. Initially made up of several chiefdoms, it came to be dominated by the Pictish kingdom of Fortriu from the seventh century. During this Verturian hegemony, Picti was adopted as an endonym. This lasted around 160 years until the Pictish kingdom merged with that of Dál Riata to form the Kingdom of Alba, ruled by the House of Alpin. The concept of "Pictish kingship" continued for a few decades until it was abandoned during the reign of Caustantín mac Áeda.

Dál Riata or Dál Riada was a Gaelic kingdom that encompassed the western seaboard of Scotland and north-eastern Ireland, on each side of the North Channel. At its height in the 6th and 7th centuries, it covered what is now Argyll in Scotland and part of County Antrim in Northern Ireland. After a period of expansion, Dál Riata eventually became associated with the Gaelic Kingdom of Alba.

A torc, also spelled torq or torque, is a large rigid or stiff neck ring in metal, made either as a single piece or from strands twisted together. The great majority are open at the front, although some have hook and ring closures and a few have mortice and tenon locking catches to close them. Many seem designed for near-permanent wear and would have been difficult to remove.

The Maeatae were a confederation of tribes that probably lived beyond the Antonine Wall in Roman Britain.

The Gundestrup cauldron is a richly decorated silver vessel, thought to date from between 200 BC and 300 AD, or more narrowly between 150 BC and 1 BC. This places it within the late La Tène period or early Roman Iron Age. The cauldron is the largest known example of European Iron Age silver work. It was found dismantled, with the other pieces stacked inside the base, in 1891, in a peat bog near the hamlet of Gundestrup in the Aars parish of Himmerland, Denmark. It is now usually on display in the National Museum of Denmark in Copenhagen, with replicas at other museums; it was in the UK on a travelling exhibition called The Celts during 2015–2016.

Malcolm Laing was a Scottish historian, advocate and politician.

The British Iron Age is a conventional name used in the archaeology of Great Britain, referring to the prehistoric and protohistoric phases of the Iron Age culture of the main island and the smaller islands, typically excluding prehistoric Ireland, which had an independent Iron Age culture of its own. The Iron Age is not an archaeological horizon of common artefacts but is rather a locally-diverse cultural phase.

The culture of Scotland refers to the patterns of human activity and symbolism associated with Scotland and the Scottish people. The Scottish flag is blue with a white saltire, and represents the cross of Saint Andrew.

Celtic art is associated with the peoples known as Celts; those who spoke the Celtic languages in Europe from pre-history through to the modern period, as well as the art of ancient peoples whose language is uncertain, but have cultural and stylistic similarities with speakers of Celtic languages.

The Britons, also known as Celtic Britons or Ancient Britons, were the indigenous Celtic people who inhabited Great Britain from at least the British Iron Age until the High Middle Ages, at which point they diverged into the Welsh, Cornish, and Bretons. They spoke Common Brittonic, the ancestor of the modern Brittonic languages.

The Roman era in the area of modern Wales began in 48 AD, with a military invasion by the imperial governor of Roman Britain. The conquest was completed by 78 AD, and Roman rule endured until the region was abandoned in 383 AD.

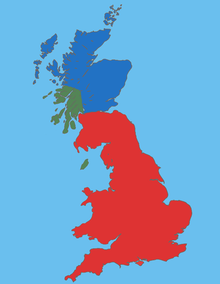

Scotland was divided into a series of kingdoms in the Early Middle Ages, i.e. between the end of Roman authority in southern and central Britain from around 400 AD and the rise of the kingdom of Alba in 900 AD. Of these, the four most important to emerge were the Picts, the Gaels of Dál Riata, the Britons of Alt Clut, and the Anglian kingdom of Bernicia. After the arrival of the Vikings in the late 8th century, Scandinavian rulers and colonies were established on the islands and along parts of the coasts. In the 9th century, the House of Alpin combined the lands of the Scots and Picts to form a single kingdom which constituted the basis of the Kingdom of Scotland.

The National Museum of Ireland – Archaeology is a branch of the National Museum of Ireland located on Kildare Street in Dublin, Ireland, that specialises in Irish and other antiquities dating from the Stone Age to the Late Middle Ages.

The Torrs Horns and Torrs Pony-cap are Iron Age bronze pieces now in the National Museum of Scotland, which were found together, but whose relationship is one of many questions about these "famous and controversial" objects that continue to be debated by scholars. Most scholars agree that horns were added to the pony-cap at a later date, but whether they were originally made for this purpose is unclear; one theory sees them as mounts for drinking-horns, either totally or initially unconnected to the cap. The three pieces are decorated in a late stage of La Tène style, as Iron Age Celtic art is called by archaeologists. The dates ascribed to the elements vary, but are typically around 200 BC; it is generally agreed that the horns are somewhat later than the cap, and in a rather different style.

In the early Middle Ages, there were distinct material cultures evident in the different federations and kingdoms within what is now Scotland. Pictish art was the only uniquely Scottish medieval style; it can be seen in the extensive survival of carved stones, particularly in the north and east of the country, which hold a variety of recurring images and patterns. It can also be seen in elaborate metal work that largely survives in buried hoards. Irish-Scots art from the kingdom of Dál Riata suggests that it was one of the places, as a crossroads between cultures, where the Insular style developed.

Hillforts in Scotland are earthworks, sometimes with wooden or stone enclosures, built on higher ground, which usually include a significant settlement, built within the modern boundaries of Scotland. They were first studied in the eighteenth century and the first serious field research was undertaken in the nineteenth century. In the twentieth century there were large numbers of archaeological investigations of specific sites, with an emphasis on establishing a chronology of the forts. Forts have been classified by type and their military and ritual functions have been debated.

Prehistoric art in Scotland is visual art created or found within the modern borders of Scotland, before the departure of the Romans from southern and central Britain in the early fifth century CE, which is usually seen as the beginning of the early historic or Medieval era. There is no clear definition of prehistoric art among scholars and objects that may involve creativity often lack a context that would allow them to be understood.

The Christianisation of Scotland was the process by which Christianity spread in what is now Scotland, which took place principally between the fifth and tenth centuries.

This is a bibliography of published works on the history of Wales. It includes published books, journals, and educational and academic history-related websites; it does not include self-published works, blogs or user-edited sites. Works may cover aspects of Welsh history inclusively or exclusively.

References

- ↑ Current Archaeology - Issues 181-192 - Page 312 2002 "Lloyd Laing is an exception. The book is exactly what its title implies: a complete introduction to the whole British ceramic sequence. With numerous line drawings and top—quality colour pictures of potsherds (by archaeologist wife Jenny), it is ..."

- ↑ Lloyd Laing Later Celtic Art 1987 - Page 58 "He was born in Scotland, where he studied prehistoric archaeology and fine art at Edinburgh University, before becoming assistant inspector of ancient monuments for Scotland, a post he held from 1966 to 1969."

- ↑ Archaeology research projects - The University of Nottingham