Related Research Articles

A bacteriophage, also known informally as a phage, is a virus that infects and replicates within bacteria and archaea. The term is derived from Ancient Greek φαγεῖν (phagein) 'to devour' and bacteria. Bacteriophages are composed of proteins that encapsulate a DNA or RNA genome, and may have structures that are either simple or elaborate. Their genomes may encode as few as four genes and as many as hundreds of genes. Phages replicate within the bacterium following the injection of their genome into its cytoplasm.

Enterobacteria phage λ is a bacterial virus, or bacteriophage, that infects the bacterial species Escherichia coli. It was discovered by Esther Lederberg in 1950. The wild type of this virus has a temperate life cycle that allows it to either reside within the genome of its host through lysogeny or enter into a lytic phase, during which it kills and lyses the cell to produce offspring. Lambda strains, mutated at specific sites, are unable to lysogenize cells; instead, they grow and enter the lytic cycle after superinfecting an already lysogenized cell.

A provirus is a virus genome that is integrated into the DNA of a host cell. In the case of bacterial viruses (bacteriophages), proviruses are often referred to as prophages. However, proviruses are distinctly different from prophages and these terms should not be used interchangeably. Unlike prophages, proviruses do not excise themselves from the host genome when the host cell is stressed.

A prophage is a bacteriophage genome that is integrated into the circular bacterial chromosome or exists as an extrachromosomal plasmid within the bacterial cell. Integration of prophages into the bacterial host is the characteristic step of the lysogenic cycle of temperate phages. Prophages remain latent in the genome through multiple cell divisions until activation by an external factor, such as UV light, leading to production of new phage particles that will lyse the cell and spread. As ubiquitous mobile genetic elements, prophages play important roles in bacterial genetics and evolution, such as in the acquisition of virulence factors.

Transduction is the process by which foreign DNA is introduced into a cell by a virus or viral vector. An example is the viral transfer of DNA from one bacterium to another and hence an example of horizontal gene transfer. Transduction does not require physical contact between the cell donating the DNA and the cell receiving the DNA, and it is DNase resistant. Transduction is a common tool used by molecular biologists to stably introduce a foreign gene into a host cell's genome.

The lytic cycle is one of the two cycles of viral reproduction, the other being the lysogenic cycle. The lytic cycle results in the destruction of the infected cell and its membrane. Bacteriophages that can only go through the lytic cycle are called virulent phages.

In virology, temperate refers to the ability of some bacteriophages to display a lysogenic life cycle. Many temperate phages can integrate their genomes into their host bacterium's chromosome, together becoming a lysogen as the phage genome becomes a prophage. A temperate phage is also able to undergo a productive, typically lytic life cycle, where the prophage is expressed, replicates the phage genome, and produces phage progeny, which then leave the bacterium. With phage the term virulent is often used as an antonym to temperate, but more strictly a virulent phage is one that has lost its ability to display lysogeny through mutation rather than a phage lineage with no genetic potential to ever display lysogeny.

Lysogeny, or the lysogenic cycle, is one of two cycles of viral reproduction. Lysogeny is characterized by integration of the bacteriophage nucleic acid into the host bacterium's genome or formation of a circular replicon in the bacterial cytoplasm. In this condition the bacterium continues to live and reproduce normally, while the bacteriophage lies in a dormant state in the host cell. The genetic material of the bacteriophage, called a prophage, can be transmitted to daughter cells at each subsequent cell division, and later events can release it, causing proliferation of new phages via the lytic cycle.

P1 is a temperate bacteriophage that infects Escherichia coli and some other bacteria. When undergoing a lysogenic cycle the phage genome exists as a plasmid in the bacterium unlike other phages that integrate into the host DNA. P1 has an icosahedral head containing the DNA attached to a contractile tail with six tail fibers. The P1 phage has gained research interest because it can be used to transfer DNA from one bacterial cell to another in a process known as transduction. As it replicates during its lytic cycle it captures fragments of the host chromosome. If the resulting viral particles are used to infect a different host the captured DNA fragments can be integrated into the new host's genome. This method of in vivo genetic engineering was widely used for many years and is still used today, though to a lesser extent. P1 can also be used to create the P1-derived artificial chromosome cloning vector which can carry relatively large fragments of DNA. P1 encodes a site-specific recombinase, Cre, that is widely used to carry out cell-specific or time-specific DNA recombination by flanking the target DNA with loxP sites.

The mobilome is the entire set of mobile genetic elements in a genome. Mobilomes are found in eukaryotes, prokaryotes, and viruses. The compositions of mobilomes differ among lineages of life, with transposable elements being the major mobile elements in eukaryotes, and plasmids and prophages being the major types in prokaryotes. Virophages contribute to the viral mobilome.

A corynebacteriophage is a DNA-containing bacteriophage specific for bacteria of genus Corynebacterium as its host. Corynebacterium diphtheriae virus strain Corynebacterium diphtheriae phage introduces toxigenicity into strains of Corynebacterium diphtheriae as it encodes diphtheria toxin, it has subtypes beta c and beta vir. According to proposed taxonomic classification, corynephages β and ω are unclassified members of the genus Lambdavirus, family Siphoviridae.

Phage typing is a phenotypic method that uses bacteriophages for detecting and identifying single strains of bacteria. Phages are viruses that infect bacteria and may lead to bacterial cell lysis. The bacterial strain is assigned a type based on its lysis pattern. Phage typing was used to trace the source of infectious outbreaks throughout the 1900s, but it has been replaced by genotypic methods such as whole genome sequencing for epidemiological characterization.

Bacteriophage P2, scientific name Peduovirus P2, is a temperate phage that infects E. coli. It is a tailed virus with a contractile sheath and is thus classified in the genus Peduovirus, family Peduoviridae within class Caudoviricetes. This genus of viruses includes many P2-like phages as well as the satellite phage P4.

SaPIs are a family of ~15 kb mobile genetic elements resident in the genomes of the vast majority of S. aureus strains. Much like bacteriophages, SaPIs can be transferred to uninfected cells and integrate into the host chromosome. Unlike the bacterial viruses, however, integrated SaPIs are mobilized by host infection with "helper" bacteriophages. SaPIs are used by the host bacteria to co-opt the phage reproduction cycle for their own genetic transduction and also inhibit phage reproduction in the process.

In biology, a pathogen, in the oldest and broadest sense, is any organism or agent that can produce disease. A pathogen may also be referred to as an infectious agent, or simply a germ.

Bacteriophage T12 is a bacteriophage that infects Streptococcus pyogenes bacteria. It is a proposed species of the family Siphoviridae in the order Caudovirales also known as tailed viruses. It converts a harmless strain of bacteria into a virulent strain. It carries the speA gene which codes for erythrogenic toxin A. speA is also known as streptococcal pyogenic exotoxin A, scarlet fever toxin A, or even scarlatinal toxin. Note that the name of the gene "speA" is italicized; the name of the toxin "speA" is not italicized. Erythrogenic toxin A converts a harmless, non-virulent strain of Streptococcus pyogenes to a virulent strain through lysogeny, a life cycle which is characterized by the ability of the genome to become a part of the host cell and be stably maintained there for generations. Phages with a lysogenic life cycle are also called temperate phages. Bacteriophage T12, proposed member of family Siphoviridae including related speA-carrying bacteriophages, is also a prototypic phage for all the speA-carrying phages of Streptococcus pyogenes, meaning that its genome is the prototype for the genomes of all such phages of S. pyogenes. It is the main suspect as the cause of scarlet fever, an infectious disease that affects small children.

cII or transcriptional activator II is a DNA-binding protein and important transcription factor in the life cycle of lambda phage. It is encoded in the lambda phage genome by the 291 base pair cII gene. cII plays a key role in determining whether the bacteriophage will incorporate its genome into its host and lie dormant (lysogeny), or replicate and kill the host (lysis).

The "Kill the Winner" hypothesis (KtW) is an ecological model of population growth involving prokaryotes, viruses and protozoans that links trophic interactions to biogeochemistry. The model is related to the Lotka–Volterra equations. It assumes that prokaryotes adopt one of two strategies when competing for limited resources: priority is either given to population growth ("winners") or survival ("defenders"). As "winners" become more abundant and active in their environment, their contact with host-specific viruses increases, making them more susceptible to viral infection and lysis. Thus, viruses moderate the population size of "winners" and allow multiple species to coexist. Current understanding of KtW primarily stems from studies of lytic viruses and their host populations.

Arbitrium is a viral peptide produced by bacteriophages to communicate with each other and decide host cell fate. It is six amino acids(aa) long, and so is also referred to as a hexapeptide. It is produced when a phage infects a bacterial host. and signals to other phages that the host has been infected.

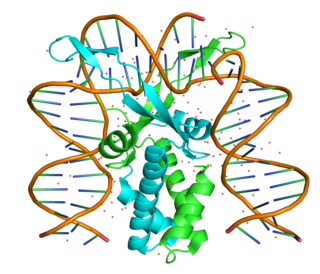

The integration host factor (IHF) is a bacterial DNA binding protein complex that facilitates genetic recombination, replication, and transcription by binding to specific DNA sequences and bending the DNA. It also facilitates the integration of foreign DNA into the host genome. It is a heterodimeric complex composed of two homologous subunits IHFalpha and IHFbeta.

References

- 1 2 Lwoff, André (December 1953). "Lysogeny". Bacteriological Reviews. 17 (4): 269–337. doi:10.1128/br.17.4.269-337.1953. PMC 180777 . PMID 13105613.

- ↑ Feiner, Ron; Argov, Tal; Rabinovich, Lev; Sigal, Nadejda; Borovok, Ilya; Herskovits, Anat A. (16 September 2015). "A new perspective on lysogeny: prophages as active regulatory switches of bacteria". Nature Reviews Microbiology. 13 (10): 641–650. doi:10.1038/nrmicro3527. PMID 26373372. S2CID 11546907.