Related Research Articles

John Brown was a prominent leader in the American abolitionist movement in the decades preceding the Civil War. First reaching national prominence in the 1850s for his radical abolitionism and fighting in Bleeding Kansas, Brown was captured, tried, and executed by the Commonwealth of Virginia for a raid and incitement of a slave rebellion at Harpers Ferry in 1859.

Oberlin is a city in Lorain County, Ohio, United States. It is located about 31 miles (50 km) southwest of Cleveland within the Cleveland metropolitan area. The population was 8,555 at the 2020 census. Oberlin is the home of Oberlin College, a liberal arts college and music conservatory with approximately 3,000 students.

Mary Edmonia Lewis, also known as "Wildfire", was an American sculptor, of mixed African-American and Native American heritage. Born free in Upstate New York, she worked for most of her career in Rome, Italy. She was the first African-American and Native American sculptor to achieve national and then international prominence. She began to gain prominence in the United States during the Civil War; at the end of the 19th century, she remained the only Black woman artist who had participated in and been recognized to any extent by the American artistic mainstream. In 2002, the scholar Molefi Kete Asante named Edmonia Lewis on his list of 100 Greatest African Americans.

Charlotte Louise Bridges Forten Grimké was an African American anti-slavery activist, poet, and educator. She grew up in a prominent abolitionist family in Philadelphia. She taught school for years, including during the Civil War, to freedmen in South Carolina. Later in life she married Francis James Grimké, a Presbyterian minister who led a major church in Washington, DC, for decades. He was a nephew of the abolitionist Grimké sisters and was active in civil rights.

John Mercer Langston was an American abolitionist, attorney, educator, activist, diplomat, and politician. He was the founding dean of the law school at Howard University and helped create the department. He was the first president of what is now Virginia State University, a historically black college. He was elected a U.S. Representative from Virginia and wrote From the Virginia Plantation to the National Capitol; Or, the First and Only Negro Representative in Congress From the Old Dominion.

The tragic mulatto is a stereotypical fictional character that appeared in American literature during the 19th and 20th centuries, starting in 1837. The "tragic mulatto" is a stereotypical mixed-race person, who is assumed to be depressed, or even suicidal, because s/he fails to completely fit into the "white world" or the "Black world". As such, the "tragic mulatto" is depicted as the victim of the society that is divided by race, where there is no place for one who is neither completely "Black" nor "white".

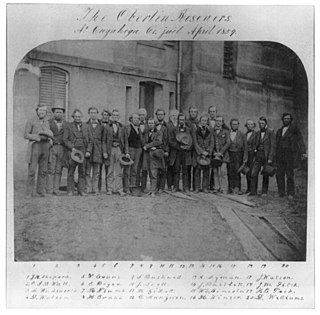

The Oberlin–Wellington Rescue of 1858 in was a key event in the history of abolitionism in the United States. A cause celèbre and widely publicized, thanks in part to the new telegraph, it is one of the series of events leading up to Civil War.

Lewis Sheridan Leary was an African-American harnessmaker from Oberlin, Ohio, who joined John Brown's raid on Harpers Ferry, where he was killed.

John Anthony Copeland Jr. was born free in Raleigh, North Carolina, one of the eight children born to John Copeland Sr. and his wife Delilah Evans, free mulattos, who married in Raleigh in 1831. Delilah was born free, while John was manumitted in the will of his master. In 1843 the family moved north, to the abolitionist center of Oberlin, Ohio, where he later attended Oberlin College's preparatory division. He was a highly visible leader in the successful Oberlin-Wellington Rescue of 1858, for which he was indicted but not tried. Copeland joined John Brown's raid on Harpers Ferry; other than Brown himself, he was the only member of John Brown's raiders that was at all well known. He was captured, and a marshal from Ohio came to Charles Town to serve him with the indictment. He was indicted a second time, for murder and conspiracy to incite slaves to rebellion. He was found guilty and was hanged on December 16, 1859. There were 1,600 spectators. His family tried but failed to recover his body, which was taken by medical students for dissection, and the bones discarded.

Osborne Perry Anderson was an African-American abolitionist and the only surviving African-American member of John Brown's raid on Harpers Ferry. He became a soldier in the Union Army during the American Civil War.

Charles Henry Langston (1817–1892) was an American abolitionist and political activist who was active in Ohio and later in Kansas, during and after the American Civil War, where he worked for black suffrage and other civil rights. He was a spokesman for blacks of Kansas and "the West".

James Mercer Langston Hughes was an American poet, social activist, novelist, playwright, and columnist from Joplin, Missouri. One of the earliest innovators of the literary art form called jazz poetry, Hughes is best known as a leader of the Harlem Renaissance. He famously wrote about the period that "the Negro was in vogue", which was later paraphrased as "when Harlem was in vogue."

Harriet Forten Purvis was an African-American abolitionist and first generation suffragist. With her mother and sisters, she formed the first biracial women's abolitionist group, the Philadelphia Female Anti-Slavery Society. She hosted anti-slavery events at her home and with her husband Robert Purvis ran an Underground Railroad station. Robert and Harriet also founded the Gilbert Lyceum. She fought against segregation and for the right for blacks to vote after the Civil War.

Mary Evans Wilson (1866-1928) was one of Boston's leading civil rights activists. She was a founding member of the Boston branch of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, and the founder of the Women's Service Club.

Anna Evans Murray (1857–1955) was an American civic leader, educator, and early advocate of free kindergarten and the training of kindergarten teachers. In 1898 she successfully lobbied Congress for the first federal funds for kindergarten classes, and introduced kindergarten to the Washington, D.C. public school system.

Nettie Langston Napier was an African-American activist for the rights of women of color during the early part of the 20th century. She lived in Nashville, Tennessee.

Carolina Mercer Langston was an American writer and actress. She was the mother of poet, playwright and social activist Langston Hughes.

Mary Jane Richardson Jones was an American abolitionist, philanthropist, and suffragist. Born in Tennessee to free black parents, Jones and her family moved to Illinois during her teenage years. Along with her husband, John Jones, she was a leading African-American figure in the early history of Chicago. The Jones household was a stop on the Underground Railroad and a center of abolitionist activity in the pre–Civil War era, helping hundreds of fugitives fleeing slavery.

"Mother to Son" is a 1922 poem written by Langston Hughes. The poem follows a mother speaking to her son about her life, which she says "ain't been no crystal stair". She first describes the struggles she has faced and then urges him to continue moving forward. It was referenced by Martin Luther King Jr. several times in his speeches during the civil rights movement, and has been analyzed by several critics, notably for its style and representation of the mother.

References

- 1 2 3 4 "The Big Sea by Langston Hughes, from Project Gutenberg Canada". gutenberg.ca. Retrieved 2023-03-16.

- ↑ Kinshasa, Kwando Mbiassi (2006). Black Resistance to the Ku Klux Klan in the Wake of the Civil War. McFarland & Company. ISBN 978-0-7864-2467-2.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Rampersad, Arnold (2002). The life of Langston Hughes. Volume I, 1902-1941. I, too, sing America (2nd ed.). Oxford. ISBN 978-0-19-976086-2. OCLC 868068746.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - 1 2 Bishir, Catherine W. (2013-11-01). Crafting Lives: African American Artisans in New Bern, North Carolina, 1770-1900. UNC Press Books. ISBN 978-1-4696-0876-1.

- 1 2 3 4 Zink, Adrian (2017). Hidden history of Kansas. Charleston, SC. ISBN 978-1-62585-889-4. OCLC 995308189.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ↑ Cheney, Anne. "The Talented Tenth and Long-Headed Jazzers." Lorraine Hansberry, Twayne, 1984, pp. 35-54. Twayne's United States Authors Series 430. Gale eBooks.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "This Shawl Belonged to Langston Hughes (True) and Was Worn by One of John B". The National Endowment for the Humanities. Retrieved 2023-03-16.

- ↑ Copeland,John A.,,Jr. (1859). Letter from john A. copeland, jr., to woodson M. habbert Retrieved from Proquest

- ↑ Kornblith, Gary J. (2018). Elusive utopia : the struggle for racial equality in Oberlin, Ohio. Carol Lasser. Baton Rouge. ISBN 978-0-8071-6956-8. OCLC 1023084688.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ↑ Meltzer, Milton (1997). Langston Hughes. Stephen Alcorn. Brookfield, Conn.: Millbrook Press. ISBN 9780761302056. OCLC 36315839.

- ↑ Langston Hughes. Great Neck Publishing. ISBN 9781429806367. OCLC 939595828.

- ↑ Ranney, D. (2000, May 9). TOUR OF BROWN SITES DRAWS DOZENS OUT. Journal-World (Lawrence, KS), p. B3

- ↑ Rampersad, Arnold. "Hughes, Langston." Encyclopedia of African-American Culture and History, edited by Colin A. Palmer, 2nd ed., vol. 3, Macmillan Reference USA, 2006, pp. 1077-1079. Gale eBooks.

- ↑ Jr, Albert Fortney (2016-01-15). The Fortney Encyclical Black History: The World's True Black History. Xlibris Corporation. ISBN 978-1-5144-3361-4.

- ↑ Morris, J. Brent (2014-09-02). Oberlin, Hotbed of Abolitionism: College, Community, and the Fight for Freedom and Equality in Antebellum America. UNC Press Books. ISBN 978-1-4696-1828-9.

- ↑ Gruner, Mariah (2021-06-01). "Enslavement and Its Legacies: "May the points of our needles prick": Antislavery Needlework and the Cultivation of the Abolitionist Self". Winterthur Portfolio. 55 (2–3): 85–120. doi:10.1086/718714. ISSN 0084-0416. S2CID 248325200.

- ↑ Quarles, Benjamin (1974). Allies for Freedom: Blacks and John Brown. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-501770-0.

- ↑ Lubet, Steven (2015-08-27). The 'Colored Hero' of Harper's Ferry: John Anthony Copeland and the War against Slavery. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-316-35220-5.

- ↑ "Mary Sampson Patterson Langston, Marker". luna.ku.edu. Retrieved 2023-03-30.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Rhynes, Martha E. (2002). I, too, sing America : the story of Langston Hughes. Greensboro, N.C.: Morgan Reynolds. ISBN 1-883846-89-7. OCLC 48473854.

- ↑ Douglas, S. A. (1863, Jun 09). Letter from sattira A. douglas to robert hamilton, 9 june 1863. Weekly Anglo-African Retrieved from Proquest.

- ↑ Shannon, Ronald (June 2008). Profiles in Ohio History: A Legacy of African American Achievement. iUniverse. ISBN 978-0-595-47716-6.

- ↑ Christensen, Lawrence O.; Foley, William E.; Kremer, Gary (October 1999). Dictionary of Missouri Biography. University of Missouri Press. ISBN 978-0-8262-6016-1.

- ↑ Bloom, Harold, ed. (1998). Langston Hughes : comprehensive research and study guide. Broomall, PA: Chelsea House Publishers. ISBN 9780585244662. OCLC 44963345.

- ↑ Dean, Virgil W. (2015-10-12). Lawrence. Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4396-5358-6.

- 1 2 Miller, R. Baxter, ed. (2013). Langston Hughes. R. Baxter Miller. Ipswich, Mass.: Salem Press. ISBN 9781429837729. OCLC 816638054.

- ↑ Poets, Academy of American. "Aunt Sue's Stories by Langston Hughes - Poems | Academy of American Poets". poets.org. Retrieved 2023-03-16.

- ↑ Hill-Lubin, Mildred A. (October 1991). "The African-American Grandmother in Autobiographical Works by Frederick Douglass, Langston Hughes, and Maya Angelou". The International Journal of Aging and Human Development. 33 (3): 173–185. doi:10.2190/4XJ4-42N4-LD4J-12ER. ISSN 0091-4150. PMID 1955211. S2CID 3158435.

- ↑ "Langston Hughes's Grandma Mary Writes a Love Letter to Lewis Leary Years after He Dies Fighting at Harper's Ferry, Erica Dawson". blackbird.vcu.edu. Retrieved 2023-03-30.