The Mandan, Hidatsa, and Arikara Nation, also known as the Three Affiliated Tribes, is a federally recognized Native American Nation resulting from the alliance of the Mandan, Hidatsa, and Arikara peoples, whose Indigenous lands ranged across the Missouri River basin extending from present day North Dakota through western Montana and Wyoming.

The Arikara War was a military conflict between the United States and Arikara in 1823 fought in the Great Plains along the Upper Missouri River in the Unorganized Territory. For the United States, the war was the first in which the United States Army was deployed for operations west of the Missouri River on the Great Plains. The war, the first and only conflict between the Arikara and the U.S., came as a response to an Arikara attack on U.S. citizens engaged in the fur trade. The Arikara War was called "the worst disaster in the history of the Western fur trade".

Prince Alexander Philipp Maximilian zu Wied-Neuwied was a German explorer, ethnologist and naturalist. He led a pioneering expedition to southeast Brazil between 1815 and 1817, from which the album Reise nach Brasilien, which first revealed to Europe real images of Brazilian Indians, was the ultimate result. It was translated into several languages and recognized as one of the greatest contributions to the European knowledge of Brazil at the beginning of the nineteenth century. In 1832 he embarked on another expedition, this time to the United States, together with the Swiss painter Karl Bodmer.

The Hidatsa are a Siouan people. They are enrolled in the federally recognized Three Affiliated Tribes of the Fort Berthold Reservation in North Dakota. Their language is related to that of the Crow, and they are sometimes considered a parent tribe to the modern Crow in Montana.

The Arikara, also known as Sahnish, Arikaree, Ree, or Hundi, are a tribe of Native Americans in North Dakota. Today, they are enrolled with the Mandan and the Hidatsa as the federally recognized tribe known as the Mandan, Hidatsa, and Arikara Nation.

Mandan is an extinct Siouan language of North Dakota in the United States.

The Mandan are a Native American tribe of the Great Plains who have lived for centuries primarily in what is now North Dakota. They are enrolled in the Three Affiliated Tribes of the Fort Berthold Reservation. About half of the Mandan still reside in the area of the reservation; the rest reside around the United States and in Canada.

Fort Mandan was the name of the encampment which the Lewis and Clark Expedition built for wintering over in 1804–1805. The encampment was located on the Missouri River approximately twelve miles (19 km) from the site of present-day Washburn, North Dakota, which developed later. The precise location is not known for certain. It is believed now to be under the water of the river. A replica of the fort has been constructed near the original site.

Fort Abraham Lincoln State Park is a North Dakota state park located 7 miles (11 km) south of Mandan, North Dakota, United States. The park is home to the replica Mandan On-A-Slant Indian Village and reconstructed military buildings including the Custer House.

The Knife River Indian Villages National Historic Site, which was established in 1974, preserves the historic and archaeological remnants of bands of Hidatsa, Northern Plains Indians, in North Dakota. This area was a major trading and agricultural area. Three villages were known to occupy the Knife area. In general, these three villages are known as Hidatsa villages. Broken down, the individual villages are Awatixa Xi'e, Awatixa and Big Hidatsa village. Awatixa Xi'e is believed to be the oldest village of the three. The Big Hidatsa village was established around 1600.

The Hunkpapa are a Native American group, one of the seven council fires of the Lakota tribe. The name Húŋkpapȟa is a Lakota word, meaning "Head of the Circle". By tradition, the Húŋkpapȟa set up their lodges at the entryway to the circle of the Great Council when the Sioux met in convocation. They speak Lakȟóta, one of the three dialects of the Sioux language.

The Fort Berthold Indian Reservation is a U.S. Indian reservation in western North Dakota that is home for the federally recognized Mandan, Hidatsa, and Arikara Nation, also known as the Three Affiliated Tribes. The reservation includes lands on both sides of the Missouri River. The tribal headquarters is in New Town, the 18th largest city in North Dakota.

Like-a-Fishhook Village was a Native American settlement next to Fort Berthold in North Dakota, United States, established by dissident bands of the Three Affiliated Tribes, the Mandan, Arikara and Hidatsa. Formed in 1845, it was also eventually inhabited by non-Indian traders, and became important in the trade between Natives and non-Natives in the region.

An earth lodge is a semi-subterranean building covered partially or completely with earth, best known from the Native American cultures of the Great Plains and Eastern Woodlands. Most earth lodges are circular in construction with a dome-like roof, often with a central or slightly offset smoke hole at the apex of the dome. Earth lodges are well-known from the more-sedentary tribes of the Plains such as the Hidatsa, Mandan, and Arikara, but they have also been identified archaeologically among sites of the Mississippian culture in the eastern United States.

The North Dakota Lewis and Clark Interpretive Center, operated by the North Dakota Parks and Recreation Department, interprets the history of the Lewis and Clark Expedition. It focuses on the winter of 1804–1805, which they spent at Fort Mandan, a post they built near a Mandan village. The center was opened in 1997 and overlooks the Missouri River on the outskirts of Washburn, North Dakota, the center opened in 1997. It is located about two miles from the reconstructed Fort Mandan.

Fort Clark Trading Post State Historic Site was once the home to a Mandan and later an Arikara settlement. Over the course of its history it also had two factories. Today only archeological remains survive at the site located eight miles west of Washburn, North Dakota, United States.

The 1837 Great Plains smallpox epidemic spanned 1836 through 1840, reaching its height after the spring of 1837, when an American Fur Company steamboat, the SS St. Peter, carried infected people and supplies up the Missouri River in the Midwestern United States. The disease spread rapidly to indigenous populations with no natural immunity, causing widespread illness and death across the Great Plains, especially in the Upper Missouri River watershed. More than 17,000 Indigenous people died along the Missouri River alone, with some bands becoming nearly extinct.

Fort Berthold was the name of two successive forts on the upper Missouri River in present-day central-northwest North Dakota. Both were initially established as fur trading posts. The second was adapted as a post for the U.S. Army. After the Army left the area, having subdued Native Americans, the fort was used by the US as the Indian Agency for the regional Arikara, Hidatsa, and Mandan Affiliated Tribes and their reservation.

A burial tree or burial scaffold is a tree or simple structure used for supporting corpses or coffins. They were once common among the Balinese, the Naga people, certain Aboriginal Australians, and the Sioux and other North American First Nations.

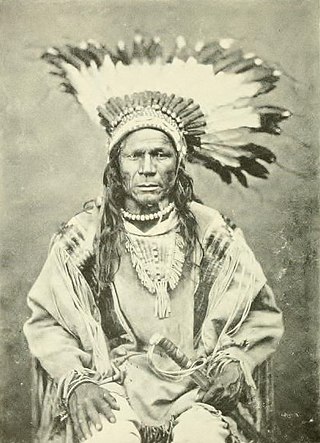

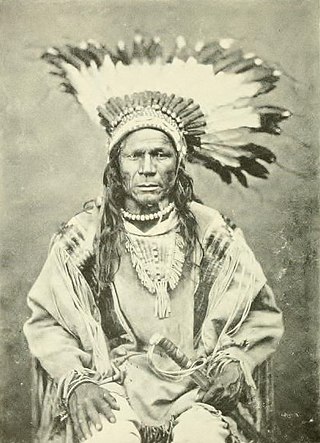

Crow Flies High was the chief of a band of dissident Hidatsa people from 1870 until their band joined the reservation system in 1894. This band was one of the last to settle on an Indian reservation. A North Dakota State Park is named after him.