Related Research Articles

Tone is the use of pitch in language to distinguish lexical or grammatical meaning—that is, to distinguish or to inflect words. All oral languages use pitch to express emotional and other para-linguistic information and to convey emphasis, contrast and other such features in what is called intonation, but not all languages use tones to distinguish words or their inflections, analogously to consonants and vowels. Languages that have this feature are called tonal languages; the distinctive tone patterns of such a language are sometimes called tonemes, by analogy with phoneme. Tonal languages are common in East and Southeast Asia, Africa, the Americas and the Pacific.

Ganda or Luganda is a Bantu language spoken in the African Great Lakes region. It is one of the major languages in Uganda and is spoken by more than 5.56 million Baganda and other people principally in central Uganda, including the capital Kampala of Uganda. Typologically, it is an agglutinative, tonal language with subject–verb–object word order and nominative–accusative morphosyntactic alignment.

Kirundi, also known as Rundi, is a Bantu language and the national language of Burundi. It is a dialect of Rwanda-Rundi dialect continuum that is also spoken in Rwanda and adjacent parts of Tanzania, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Uganda, as well as in Kenya. Kirundi is mutually intelligible with Kinyarwanda, the national language of Rwanda, and the two form parts of the wider dialect continuum known as Rwanda-Rundi.

A pitch-accent language is a type of language that, when spoken, has certain syllables in words or morphemes that are prominent, as indicated by a distinct contrasting pitch rather than by loudness or length, as in some other languages like English. Pitch-accent also contrasts with fully tonal languages like Vietnamese, Thai and Standard Chinese, in which practically every syllable can have an independent tone. Some scholars have claimed that the term "pitch accent" is not coherently defined and that pitch-accent languages are just a sub-category of tonal languages in general.

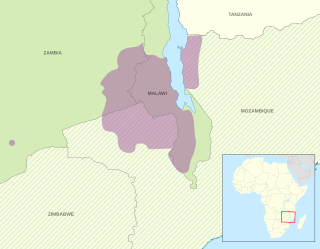

Chewa is a Bantu language spoken in Malawi and a recognised minority in Zambia and Mozambique. The noun class prefix chi- is used for languages, so the language is usually called Chichewa and Chinyanja. In Malawi, the name was officially changed from Chinyanja to Chichewa in 1968 at the insistence of President Hastings Kamuzu Banda, and this is still the name most commonly used in Malawi today. In Zambia, the language is generally known as Nyanja or Cinyanja/Chinyanja '(language) of the lake'.

In phonetics, downdrift is the cumulative lowering of pitch in the course of a sentence due to interactions among tones in a tonal language. Downdrift often occurs when the tones in successive syllables are H L H or H L L H. In this case the second high tone tends to be lower than the first. The effect can accumulate so that with each low tone, the pitch of the high tones becomes slightly lower, until the end of the intonational phrase, when the pitch is "reset".

The Tumbuka language is a Bantu language which is spoken in Malawi, Zambia, and Tanzania. It is also known by the autonym Chitumbuka also spelled Citumbuka — the chi- prefix in front of Tumbuka means "in the manner of", and is understood in this case to mean "the language of the Tumbuka people". Tumbuka belongs to the same language group as Chewa and Sena.

Tonga (Chitonga), also known as Zambezi, is a Bantu language primarily spoken by the Tonga people (Batonga) who live mainly in the Southern province, Lusaka province, Central Province and Western province of Zambia, and in northern Zimbabwe, with a few in Mozambique. The language is also spoken by the Iwe, Toka and Leya people, and perhaps by the Kafwe Twa, as well as many bilingual Zambians and Zimbabweans. In Zambia Tonga is taught in schools as first language in the whole of Southern Province, Lusaka and Central Provinces.

The obligatory contour principle is a hypothesis in autosegmental phonology that states that (certain) consecutive identical features are banned in underlying representations. The OCP is most frequently cited when discussing the tones of tonal languages, but it has also been applied to other aspects of phonology. The principle is part of the larger notion of horror aequi, that language users generally avoid repetition of identical linguistic structures.

In linguistics, upstep is a phonemic or phonetic upward shift of tone between the syllables or words of a tonal language. It is best known in the tonal languages of Sub-Saharan Africa. Upstep is a much rarer phenomenon than its counterpart, downstep.

Like most other Niger–Congo languages, Sesotho is a tonal language, spoken with two basic tones, high (H) and low (L). The Sesotho grammatical tone system is rather complex and uses a large number of "sandhi" rules.

Malawi Lomwe, known as Elhomwe, is a dialect of the Lomwe language spoken in southeastern Malawi in parts such as Mulanje and Thyolo.

Zulu grammar is the way in which meanings are encoded into wordings in the Zulu language. Zulu grammar is typical for Bantu languages, bearing all the hallmarks of this language family. These include agglutinativity, a rich array of noun classes, extensive inflection for person, tense and aspect, and a subject–verb–object word order.

Jita is a Bantu language of Tanzania, spoken on the southeastern shore of Lake Victoria/Nyanza and on the island of Ukerewe.

Tonga is a Bantu language spoken mainly in the Nkhata Bay District of Malawi. The number of speakers is estimated to be 170,000. According to the Mdawuku wa Atonga (MWATO) there are also significant numbers of speakers living elsewhere in Malawi and in neighbouring countries.

Chichewa is the main language spoken in south and central Malawi, and to a lesser extent in Zambia, Mozambique and Zimbabwe. Like most other Bantu languages, it is tonal; that is to say, pitch patterns are an important part of the pronunciation of words. Thus, for example, the word chímanga (high-low-low) 'maize' can be distinguished from chinangwá (low-low-high) 'cassava' not only by its consonants but also by its pitch pattern. These patterns remain constant in whatever context the nouns are used.

The term boundary tone refers to a rise or fall in pitch that occurs in speech at the end of a sentence or other utterance, or, if a sentence is divided into two or more intonational phrases, at the end of each intonational phrase. It can also refer to a low or high intonational tone at the beginning of an utterance or intonational phrase.

Luganda, the language spoken by the Baganda people from Central Uganda, is a tonal language of the Bantu family. It is traditionally described as having three tones: high, low and falling. Rising tones are not found in Luganda, even on long vowels, since a sequence such as [] automatically becomes [].

Chichewa is the main lingua franca of central and southern Malawi and neighbouring regions. Like other Bantu languages it has a wide range of tenses. In terms of time, Chichewa tenses can be divided into present, recent past, remote past, near future, and remote future. The dividing line between near and remote tenses is not exact, however. Remote tenses cannot be used of events of today, but near tenses can be used of events earlier or later than today.

Achille Emile Meeussen, also spelled Achiel Emiel Meeussen, or simply A.E. Meeussen (1912–1978) was a distinguished Belgian specialist in Bantu languages, particularly those of the Belgian Congo, Rwanda and Burundi. Together with the British scholar Malcolm Guthrie (1903–1972) he is regarded as one of the two leading experts in Bantu languages in the second half of the 20th century.

References

- ↑ Pennington, Ryan. "Tone in Gadsup Noun Phrases". sil.org. Linguistics Society of PNG. Retrieved 28 December 2023.

- ↑ Goldsmith (1981).

- ↑ Google ngrams.

- ↑ Meeussen (1963)

- ↑ Goldsmith (1984b), pp. 29, 50.

- ↑ See Laura Downing in Hulst, Harry van der; Goedemans, Rob; Zanten, Ellen van (2010) A Survey of Word Accentual Patterns in the Languages of the World. de Gruyter, p. 412.

- ↑ Hyman & Katamba (1993), pp. 36, 45.

- ↑ Myers (1997), p. 864.

- ↑ Kanerva (1990), p. 59.

- ↑ Myers, (1997), p. 870.

- ↑ Hyman, Larry M. & Al D. Mtenje (1999). "Prosodic Morphology and tone: the case of Chichewa" in René Kager, Harry van der Hulst and Wim Zonneveld (eds.) The Prosody-Morphology Interface. Cambridge University Press, 90-133.