Related Research Articles

Erasmus Reinhold was a German astronomer and mathematician, considered to be the most influential astronomical pedagogue of his generation. He was born and died in Saalfeld, Saxony.

Philip Melanchthon was a German Lutheran reformer, collaborator with Martin Luther, the first systematic theologian of the Protestant Reformation, intellectual leader of the Lutheran Reformation, and an influential designer of educational systems. He stands next to Luther and John Calvin as a reformer, theologian, and shaper of Protestantism.

Georg Joachim de Porris, also known as Rheticus, was a mathematician, astronomer, cartographer, navigational-instrument maker, medical practitioner, and teacher. He is perhaps best known for his trigonometric tables and as Nicolaus Copernicus's sole pupil. He facilitated the publication of his master's De revolutionibus orbium coelestium.

Joachim Camerarius, the Elder, was a German classical scholar.

Leonhart Fuchs, sometimes spelled Leonhard Fuchs and cited in Latin as Leonhartus Fuchsius, was a German physician and botanist. His chief notability is as the author of a large book about plants and their uses as medicines, a herbal, which was first published in 1542 in Latin. It has about 500 accurate and detailed drawings of plants, which were printed from woodcuts. The drawings are the book's most notable advance on its predecessors. Although drawings had been used in other herbal books, Fuchs' book proved and emphasized high-quality drawings as the most telling way to specify what a plant name stands for.

Caspar Peucer was a German reformer, physician, and scholar of Sorbian origin.

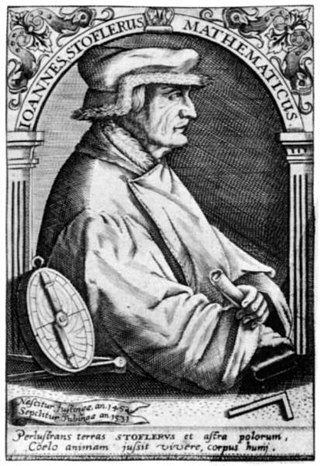

Johannes Stöffler was a German mathematician, astronomer, astrologer, priest, maker of astronomical instruments and professor at the University of Tübingen.

De revolutionibus orbium coelestium is the seminal work on the heliocentric theory of the astronomer Nicolaus Copernicus (1473–1543) of the Polish Renaissance. The book, first printed in 1543 in Nuremberg, Holy Roman Empire, offered an alternative model of the universe to Ptolemy's geocentric system, which had been widely accepted since ancient times.

Johann Georg Faust, also known in English as John Faustus, was a German itinerant alchemist, astrologer, and magician of the German Renaissance.

Tetrabiblos (Τετράβιβλος) 'four books', also known in Greek as Apotelesmatiká (Ἀποτελεσματικά) "Effects", and in Latin as Quadripartitum "Four Parts", is a text on the philosophy and practice of astrology, written in the 2nd century AD by the Alexandrian scholar Claudius Ptolemy.

Luca Gaurico was an Italian astrologer, astronomer, astrological data collector, and mathematician. He was born to a poor family in the Kingdom of Naples, and studied judicial astrology, a subject he defended in his Oratio de Inventoribus et Astrologiae Laudibus (1508). Judicial astrology concerned the fate of man as influenced by the stars. His most famous work is the Tractatus Astrologicus. Later in life he was named a bishop of the Catholic Church.

Achilles Pirmin Gasser was a German physician and astrologer. He is now known as a well-connected humanistic scholar, and supporter of both Copernicus and Rheticus.

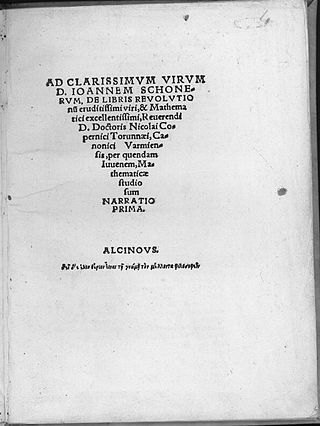

De libris revolutionum Copernici narratio prima, usually referred to as Narratio Prima, is an abstract of Nicolaus Copernicus' heliocentric theory, written by Georg Joachim Rheticus in 1540. It is an introduction to Copernicus's major work, De revolutionibus orbium coelestium, published in 1543, largely due to Rheticus's instigation. Narratio Prima is the first printed publication of Copernicus's theory.

John of Saxony or Johannes de Saxonia or John Danko or Dancowe of Saxony was a medieval astronomer. Although his exact birthplace is unknown it is believed he was born in Germany, most likely Magdeburg. His scholarly work is believed to date from the end of the 13th century into the mid 14th century. He spent most of his active career, from about 1327 to 1355, at the University of Paris.

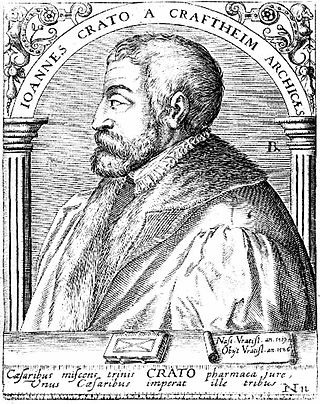

Johannes Crato von Krafftheim was a German humanist and court physician to three Holy Roman emperors.

Johann Carion was a German astrologer, known also for historical writings.

The Wittenberg Interpretation refers to the work of astronomers and mathematicians at the University of Wittenberg in response to the heliocentric model of the Solar System proposed by Nicholas Copernicus, in his 1543 book De revolutionibus orbium coelestium. The Wittenberg Interpretation fostered an acceptance of the heliocentric model and had a part in beginning the Scientific Revolution.

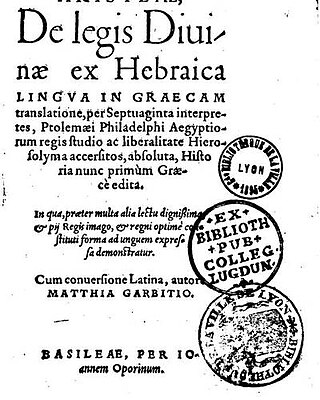

Matthias Garbitius or Matija Grbić was a German humanist, classical philologist and translator. Born in Istria, he emigrated to Nuremberg. Between 1545 and 1557 he was the dean of the philosophical faculty at the University of Tübingen. He is the first known Protestant from the Balkans.

Johannes Schott was a book printer from Strasbourg. He printed a large number of books, including tracts from Martin Luther and other Reformers. He was a well-educated man, who had relationships with some of the leading humanists of his time. His press also was one of the first to be able to print chiaroscuro woodcuts.

References

- Lynn Thorndike, in a chapter "The Circle of Melanchthon" in his multi-volume History of Magic and Experimental Science. It appears as Chapter XVII in what Google Books has as Part 9, but that is from a paperback edition not respecting the original structure of 8 volumes.