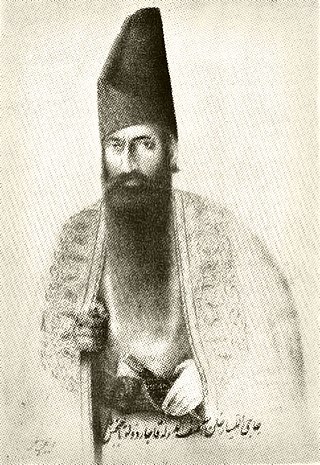

Mohammad Shah was the third Qajar shah of Iran from 1834 to 1848, inheriting the throne from his grandfather, Fath-Ali Shah. From a young age, Mohammad Mirza was under the tutelage of Haji Mirza Aqasi, a local dervish from Tabriz whose teachings influenced the young prince to become a Sufi-king later in his life. After his father Abbas Mirza died in 1833, Mohammad Mirza became the crown prince of Iran and was assigned with the governorship of Azarbaijan. After the death of Fath-Ali Shah in 1838, some of his sons including Hossein Ali Mirza and Ali Mirza Zel as-Soltan rose up as claimants to the throne. With the support of English and Russian forces, Mohammad Shah suppressed the rebellious princes and asserted his authority.

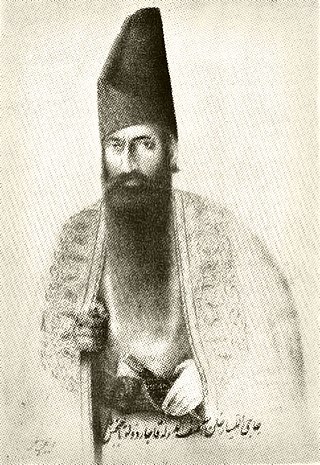

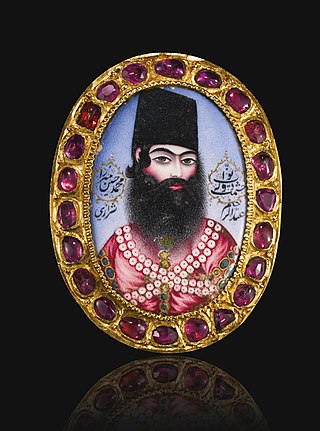

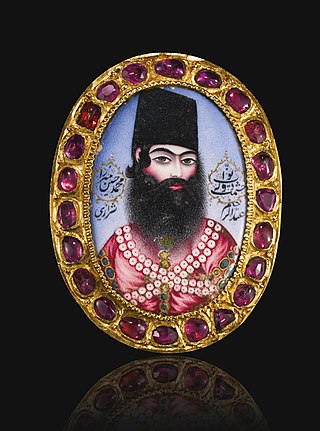

Fath-Ali Shah Qajar was the second Shah (king) of Qajar Iran. He reigned from 17 June 1797 until his death on 24 October 1834. His reign saw the irrevocable ceding of Iran's northern territories in the Caucasus, comprising what is nowadays Georgia, Dagestan, Azerbaijan, and Armenia, to the Russian Empire following the Russo-Persian Wars of 1804–1813 and 1826–1828 and the resulting treaties of Gulistan and Turkmenchay. Historian Joseph M. Upton says that he "is famous among Iranians for three things: his exceptionally long beard, his wasp-like waist, and his progeny."

Mohammad-Ali Mirza Dowlatshah was a famous Iranian Prince of the Qajar dynasty. He is also the progenitor of the Dowlatshahi Family of Persia. He was born at Nava, in Mazandaran, a Caspian province in the north of Iran. He was the first son of Fath-Ali Shah, the second Qajar king of Persia, and Ziba Chehr Khanoum, a Georgian girl of the Tsikarashvili family. He was also the elder brother of Abbas Mirza. Dowlatshah was the governor of Fars at age 9, Qazvin and Gilan at age 11, Khuzestan and Lorestan at age 16, and Kermanshah at age 19.

The Nakhichevan Khanate was a khanate under Iranian suzerainty, which controlled the city of Nakhichevan and its surroundings from 1747 to 1828.

Mirza Abol-Qasem Qa'em-Maqam Farahani, also known as Qa'em-Maqam II, was an Iranian official and prose writer, who played a central role in Iranian politics in first half of the 19th-century, as well as in Persian literature.

Bahram Mirza Moezz-od-Dowleh was a Qajar prince, statesman and governor in 19th-century Iran. The second son of the crown prince Abbas Mirza, he served as the Minister of Justice from 1878 until his death on 21 October 1882.

Mirza Saleh Shirāzi was an Iranian court translator and diplomat, who published the first newspaper in Iran in 1837, the Kaghaz-e Akhbar.

Mirza Abolhassan Khan Ilchi was an Iranian politician and diplomat who served as the Minister of Foreign Affairs twice, first from 1824 to 1834, and then again from 1838 until his death in 1845. He also served as the ambassador to Russia and Britain, and was the main Iranian delegate at the signing of the Golestan and Turkmenchay treaties with Russia in 1813 and 1828 respectively.

Qajar Iran, also referred to as Qajar Persia, the Qajar Empire, Sublime State of Persia, officially the Sublime State of Iran and also known as the Guarded Domains of Iran, was an Iranian state ruled by the Qajar dynasty, which was of Turkic origin, specifically from the Qajar tribe, from 1789 to 1925. The Qajar family took full control of Iran in 1794, deposing Lotf 'Ali Khan, the last Shah of the Zand dynasty, and re-asserted Iranian sovereignty over large parts of the Caucasus. In 1796, Agha Mohammad Khan Qajar seized Mashhad with ease, putting an end to the Afsharid dynasty. He was formally crowned as Shah after his punitive campaign against Iran's Georgian subjects.

Manuchehr Khan Gorji Mo'tamed al-Dowleh was a eunuch in Qajar Iran, who became one of the most powerful statesmen of the country in the first half of the 19th-century.

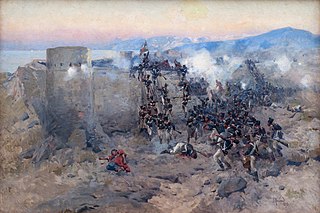

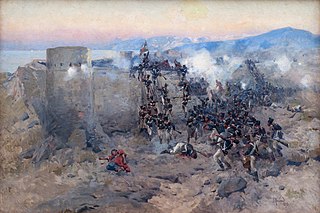

The siege of Lankaran took place from 7 January to 13 January 1813 during the Russo-Iranian War of 1804–1813. Lankaran, a city in the Talish region, was previously held by Mir-Mostafa Khan of the Talysh Khanate, a subject of Iran. However, due to his defiance, he was ousted from the city by Iranian forces in August 1812. Now directly held by the Iranians, the city was soon besieged by the Russian commander Pyotr Kotlyarevsky, who had recently defeated the Iranian crown-prince Abbas Mirza at the battle of Aslanduz.

Haji Mirza Abbas Iravani, better known by his title of Aqasi, was an Iranian politician, who served as the grand vizier of the Qajar king (shah) Mohammad Shah Qajar from 1835 to 1848.

The Guarded Domains of Iran, or simply the Domains of Iran and the Guarded Domains, was the common and official name of Iran from the Safavid era, until the early 20th century. The idea of the Guarded Domains illustrated a feeling of territorial and political uniformity in a society where the Persian language, culture, monarchy, and Shia Islam became integral elements of the developing national identity.

Hossein Ali Mirza, a son of Fath-Ali Shah, was the Governor of Fars and pretender to the throne of Qajar Iran.

Allahyar Khan Devellu-Qajar Asef al-Dowleh was the prime minister of Qajar Iran under shah (king) Fath-Ali Shah Qajar from 1824 to 1828.

Mirza Asadollah Nuri was an Iranian official who served as the revenue officer under the first two Qajar shahs (kings) of Iran, Agha Mohammad Khan Qajar and Fath-Ali Shah Qajar. He belonged to the prominent Khajeh Nouri family of Nur district in the region of Mazandaran. He was the father of Mirza Aqa Khan Nuri, who served as the prime minister under Naser al-Din Shah Qajar from 1851 to 1858.

Soleyman Khan Qajar was a military commander under his maternal cousin Agha Mohammad Khan Qajar, the founder of the Qajar dynasty of Iran. In 1799, Soleyman Khan and Mirza Bozorg Qa'em-Maqam were appointed as the adjutants of the crown prince Abbas Mirza. Soleyman Khan remained with him until his death in 1806.

The Nezam-e Jadid was a project started by the Qajar crown prince Abbas Mirza to build an up-to-date Iranian army capable of fighting in a modern environment. Its name and military reforms resembled that of the Ottoman Nizam-I Cedid reforms made by the Ottoman Sultan Selim III.

Pir Qoli Khan Qajar was an Iranian commander under the Qajar shahs (kings) Agha Mohammad Khan Qajar and Fath-Ali Shah Qajar. During the Russo-Iranian War of 1804–1813, Pir Qoli Khan was a high-ranking commander under the crown prince Abbas Mirza and oversaw the northern part of the battleground during the siege of Erivan in 1804.

Mohammad-Hossein Mirza was a Qajar prince, who governed Kermanshah twice, between 1821–1826 and 1829–1835. He was the eldest son of Mohammad-Ali Mirza Dowlatshah and grandson of Fath-Ali Shah Qajar.