Johnson County is a county in the U.S. state of Kansas, along the border of the state of Missouri. Its county seat is Olathe. As of the 2020 census, the population was 609,863, the most populous county in Kansas. The county was named after Thomas Johnson, a Methodist missionary who was one of the state's first settlers. Largely suburban, the county contains a number of suburbs of Kansas City, Missouri, including Overland Park, a principal city of and second most populous city in the Kansas City Metropolitan Area.

Overland Park is a city in Johnson County, Kansas, United States, and the second-most populous city in the state of Kansas. It is one of four principal cities in the Kansas City metropolitan area and the most populous suburb of Kansas City, Missouri. As of the 2020 census, the population of the city was 197,238.

The Pacific Electric Railway Company, nicknamed the Red Cars, was a privately owned mass transit system in Southern California consisting of electrically powered streetcars, interurban cars, and buses and was the largest electric railway system in the world in the 1920s. Organized around the city centers of Los Angeles and San Bernardino, it connected cities in Los Angeles County, Orange County, San Bernardino County and Riverside County.

The Missouri–Kansas–Texas Railroad was a Class I railroad company in the United States, with its last headquarters in Dallas, Texas. Established in 1865 under the name Union Pacific Railroad (UP), Southern Branch, it came to serve an extensive rail network in Texas, Oklahoma, Kansas, and Missouri. In 1988, it merged with the Missouri Pacific Railroad; today, it is part of UP.

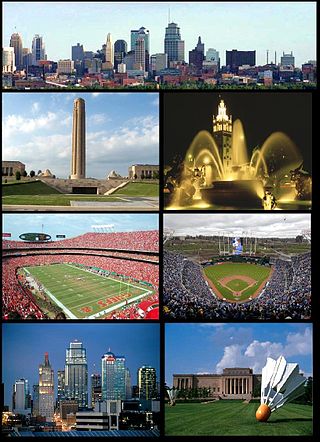

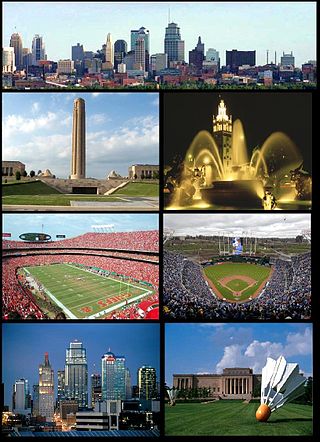

The Kansas City metropolitan area is a bi-state metropolitan area anchored by Kansas City, Missouri. Its 14 counties straddle the border between the U.S. states of Missouri and Kansas. With 8,472 square miles (21,940 km2) and a population of more than 2.2 million people, it is the second-largest metropolitan area centered in Missouri and is the largest metropolitan area in Kansas, though Wichita is the largest metropolitan area centered in Kansas. Alongside Kansas City, Missouri, these are the suburbs with populations above 100,000: Overland Park, Kansas; Kansas City, Kansas; Olathe, Kansas; Independence, Missouri; and Lee's Summit, Missouri.

New York State Railways was a subsidiary of the New York Central Railroad that controlled several large city streetcar and electric interurban systems in upstate New York. It included the city transit lines in Rochester, Syracuse, Utica, Oneida and Rome, plus various interurban lines connecting those cities. New York State Railways also held a 50% interest in the Schenectady Railway Company, but it remained a separate independent operation. The New York Central took control of the Rochester Railway Company, the Rochester and Eastern Rapid Railway and the Rochester and Sodus Bay Railway in 1905, and the Mohawk Valley Company was formed by the railroad to manage these new acquisitions. New York State Railways was formed in 1909 when the properties controlled by the Mohawk Valley Company were merged. In 1912 it added the Rochester and Suburban Railway, the Syracuse Rapid Transit Railway, the Oneida Railway, and the Utica and Mohawk Valley Railway. The New York Central Railroad was interested in acquiring these lines in an effort to control the competition and to gain control of the lucrative electric utility companies that were behind many of these streetcar and interurban railways. Ridership across the system dropped through the 1920s as operating costs continued to rise, coupled with competition from better highways and private automobile use. New York Central sold New York State Railways in 1928 to a consortium led by investor E. L. Phillips, who was looking to gain control of the upstate utilities. Phillips sold his stake to Associated Gas & Electric in 1929, and the new owners allowed the railway bonds to default. New York State Railways entered receivership on December 30, 1929. The company emerged from receivership in 1934, and local operations were sold off to new private operators between 1938 and 1948.

The Illinois Terminal Railroad Company, known as the Illinois Traction System until 1937, was a heavy duty interurban electric railroad with extensive passenger and freight business in central and southern Illinois from 1896 to 1956. When Depression era Illinois Traction was in financial distress and had to reorganize, the Illinois Terminal name was adopted to reflect the line's primary money making role as a freight interchange link to major steam railroads at its terminal ends, Peoria, Danville, and St. Louis. Interurban passenger service slowly was reduced, ending in 1956. Freight operation continued but was hobbled by tight street running in some towns requiring very sharp radius turns. In 1956, ITC was absorbed by a consortium of connecting railroads.

The Oklahoma Railway Company (ORy) operated interurban lines to El Reno, Guthrie, and Norman, and several streetcar lines in Oklahoma City, and the surrounding area from 1904 to 1947.

The Fort Collins Municipal Railway operated streetcars in Fort Collins, Colorado, from 1919 until 1951. Since 1984, a section of one of the former routes has been in operation as a seasonal heritage streetcar service, under the same name, running primarily on Spring and Summer weekends. The heritage service is operated by volunteers from the Fort Collins Municipal Railway Society (FCMRS). The streetcar in use on the heritage line, Birney "Safety" Streetcar No. 21, is listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

The Los Angeles Railway was a system of streetcars that operated in Central Los Angeles and surrounding neighborhoods between 1895 and 1963. The system provided frequent local services which complemented the Pacific Electric "Red Car" system's largely commuter-based interurban routes. The company carried many more passengers than the Red Cars, which served a larger and sparser area of Los Angeles.

The Yakima Valley Transportation Company was an interurban electric railroad headquartered in Yakima, Washington. It was operator of the city's streetcar system from 1907–1947, and it also provided the local bus service from the 1920s until 1957.

The Central California Traction Company is a Class III short-line railroad operating in the northern San Joaquin Valley, in San Joaquin County, California. It is owned jointly by the Union Pacific and BNSF Railway.

The Sacramento Northern Railway was a 183-mile (295 km) electric interurban railway that connected Chico in northern California with Oakland via the state capital, Sacramento. In its operation it ran directly on the streets of Oakland, Sacramento, Yuba City, Chico, and Woodland. This involved multiple car trains making sharp turns at street corners and obeying traffic signals. Once in open country, SN's passenger trains ran at fairly fast speeds. With its shorter route and lower fares, the SN provided strong competition to the Southern Pacific and Western Pacific Railroad for passenger business and freight business between those two cities. North of Sacramento, both passenger and freight business was less due to the small town agricultural nature of the region and due to competition from the paralleling Southern Pacific Railroad.

William B. Strang Jr. (1857–1921) was an American railroad magnate who platted Overland Park, Kansas and is considered the founder of the community. In 1905, Strang purchased 600 acres south of Kansas City, Missouri and adjacent to present day Metcalf Avenue and 80th Street. "Strang envisioned a "park-like" community that was self-sustaining and well planned. He also sought strong commerce, quality education, vibrant neighborhoods, convenient transportation and accommodating recreational facilities."

The Kansas City and Olathe Electric Railway was a 7.1-mile (11.4 km) electric interurban rail line between Kansas City, Missouri, and Olathe, Kansas. When it began operation in 1908, it ran from Rosedale, southwest through South Park to Merriam, then west to Shawnee. The road was abandoned in 1934.

Streetcars or trolley(car)s were once the chief mode of public transit in hundreds of North American cities and towns. Most of the original urban streetcar systems were either dismantled in the mid-20th century or converted to other modes of operation, such as light rail. Today, only Toronto still operates a streetcar network essentially unchanged in layout and mode of operation.

The Arkansas Valley Interurban Railway (AVI) was an interurban railway that operated in Kansas, United States, from 1910 to 1938 for passengers and to 1942 for freight, running between Wichita, Newton, and Hutchinson. It operated a small fleet of electrically powered passenger and freight equipment. Service was suspended during World War II and never resumed, except on a small portion owned the Hutchinson and Northern Railroad which is still in operation. (2020)

The Chicago and Joliet Electric Railway, or C&JE, was an electric interurban railway linking the cities of Chicago and Joliet, Illinois. It was the only interurban between those cities and provided a link between the streetcar network of Chicago and the cities along the Des Plaines River Valley in north central Illinois, which were served by the Illinois Valley Division of the Illinois Traction System.

Streetcars in Los Angeles over history have included horse-drawn streetcars and cable cars, and later extensive electric streetcar networks of the Los Angeles Railway and Pacific Electric Railway and their predecessors. Also included are modern light rail lines.